An Assessment of Probation Sentencing Reform in Louisiana and Georgia

Table of Contents

Many states have enacted comprehensive justice system reforms to reduce incarceration and community supervision in order to focus funding more on people at higher risk of reoffending and invest in strategies to achieve better outcomes for people and communities.

Many policy reforms have been spurred by significant growth in the number of people on community supervision. According to a 2018 Pew Charitable Trusts chartbook, probation and parole populations nationwide grew 239 percent from 1980 to 2016 (Horowitz, Utada, and Fuhrmann 2018). Notably, community supervision populations peaked in 2007 and then fell 11 percent between 2007 and 2016.1 To date, research on the impact of states’ community supervision policy changes has not kept pace with the rate at which they have been enacted, leaving policymakers and practitioners with a knowledge gap on which reforms have made a difference and why.

The Urban Institute and the Crime and Justice Institute (CJI) assessed policies reforming probation sentencing in two states, Louisiana and Georgia, to understand their impact on people who are supervised and on outcomes including revocation and successful completion.

Reforming probation sentencing is one way to ensure scarce resources are prioritized for supporting and monitoring people when their risk of failing supervision is highest, not for long periods after this risk has declined. Research has shown that supervision is most effective when it focuses on people who are at higher risk of reoffending and that recidivism rates drop precipitously after the first year of supervision (Alper, Durose, and Markman 2018; Andrews and Bonta 2010).

A statutory reduction of the length of probation supervision terms can be a direct way to reduce the number of people under community supervision. When implemented consistently, probation sentencing reform may yield more reliable reductions of the supervised population than reforms that depend heavily on changing supervision practices. And by limiting how long supervision resources can be expended on people at low risk of failure, these reforms can yield significant gains in cost savings and community safety. In contrast to other community supervision reforms (such as earned discharge policies) that require people to incrementally earn time off potentially lengthy sentences at the back ends of their terms, probation sentencing reform establishes upper limits that apply uniformly to entire categories of people at the front ends of their terms.

Despite these potential benefits, wholesale reductions of probation sentence lengths are uncommon. States’ strategies for reducing probation sentences have varied: some have shortened all probation sentences for certain offenses by reducing the maximum probation sentences allowed for those offenses, whereas others have simply granted judges the flexibility to impose shorter sentences than the maximums. Meanwhile, some states have used creative strategies to establish a presumption of shorter probation terms without changing sentencing requirements. These strategies blend front-end reductions of sentences with mechanisms similar to earned discharge policies that enable early release, but they also grant courts and supervising agencies discretion to extend those sentences at the back end because of noncompliance with supervision terms. For this reason, any assessment of the impact of probation sentencing reforms must consider the details of how they have been implemented and the extent to which discretion is allowed. Urban and CJI assessed implementation and analyzed outcomes of different approaches in Louisiana and Georgia.

In 2017, Louisiana’s Senate Bill 139 eliminated the one-year minimum for all probation sentences and reduced the maximum sentence for felony probation from five to three years for a first, second, or third conviction for a nonviolent, noncapital felony. Approximately 89 percent of new probation starts in 2018–19 were for nonsex, nonviolent offenses. The policy allows judges to extend probation terms up to five years for people who do not comply with supervision conditions. The law affects everyone sentenced to probation as of November 2017.

Also passed in 2017, Georgia’s Senate Bill 174 established two mechanisms for reducing probation sentence lengths. First, it requires that a probation sentence for any first-time felony conviction with a straight probation sentence (with no prison time) include a behavioral incentive date (BID) of three years or less, at which point the Georgia Department of Community Supervision (DCS) must file a petition to terminate probation if the person has not been arrested for anything other than a nonserious traffic offense during their probation term, has complied with the conditions of supervision, and has paid all restitution owed. About a third of the felony probation population from July 2017 to December 2020 was eligible for BIDs.2 Second, it makes early termination of probation available to anyone convicted of certain nonviolent felony offenses who has been sentenced to three years or more and who has not previously had their supervision revoked. The law requires DCS to file a petition for early termination for anyone who has completed three years of supervision and has not been arrested for anything other than a nonserious traffic offense, has complied with the conditions of supervision, and has paid all restitution. Courts may accept or reject BID petitions and early termination petitions at their discretion. The process the court uses for BIDs and early terminations was further clarified in legislation passed in 2021, through Senate Bill 105.3 Behavioral incentive dates went into effect in July 2017; the early termination component was made retroactive and applied to anyone serving a qualifying probation sentence of three or more years as of the effective date. Based on the data available, our analysis found about four-fifths of the felony probation dockets from July 2017 to January 2021 would be eligible for early termination.4

Urban and CJI analyzed the implementation and outcomes of both states’ policies. Our assessment explores the following three overarching questions in each state:

- How has the reform affected probation sentences imposed?

- How has the reform been implemented?

- How has the reform affected preliminary outcomes for eligible people?

Louisiana

In 2017, Louisiana passed a set of 10 bills as part of its Justice Reinvestment Initiative. Among the changes made through these bills, the state established a maximum probation term of three years for first, second, and third convictions for nonviolent, noncapital felonies. Along with other supervision reforms—including earned compliance credits and implementation of evidence-based practices including core correctional practices, graduated responses, and training on effective case management—Louisiana aimed to focus its supervision resources early in people’s supervision terms, when they are more likely to violate supervision and reoffend.

Urban and CJI found that since the probation sentencing reform was implemented in Louisiana,

- the lengths of probation sentences have declined,

- judges and probation staff have come to view shorter probation terms as having potentially positive and negative consequences on the effectiveness of probation, and

- during the implementation period, revocation rates have been trending downward and successful completion rates have gone up while probation sentence lengths have gotten shorter.

Background on Probation Sentencing Reform in Louisiana

In 2016, Louisiana’s imprisonment rate was twice the national average and the highest among all states. It was incarcerating people with nonviolent convictions at a higher rate than other southern states (Louisiana Justice Reinvestment Task Force 2017). In addition, over 70,000 people were supervised on probation or parole and the supervised population was projected to increase. At the same time that the average supervision officer’s caseload was 139 people, revocations from probation and parole made up more than 40 percent of the state’s prison population (The Pew Charitable Trusts 2018).

The goals of Louisiana’s sweeping 10-bill reform package under the Justice Reinvestment Initiative in 2017 were to focus prison beds on people convicted of more serious crimes, strengthen community supervision, clear barriers to successful reentry, and reinvest savings in recidivism reduction and crime victim support. One bill in particular, Senate Bill 139, focused on changes intended to strengthen community supervision. The focus was to implement evidence-based practices, expand eligibility for alternatives to incarceration and for early release, implement earned compliance credits, and limit felony probation to no more than three years (rather than five years) for first, second, or third convictions for noncapital felonies and remove the requirement that probation be at least one year (The Pew Charitable Trusts 2018).

In this analysis, we focus on the three-year probation limit, which was designed with exceptions and was modified slightly in subsequent years. Someone ordered to enter a specialty court program can receive a probation sentence of up to eight years, and someone can receive a probation sentence of up to five years for a first conviction for certain sex crimes or for any non–domestic violence crime that carries a 10-year maximum prison sentence. In 2018, the Louisiana legislature revised the policy to specify that probation cannot be revoked or extended solely based on someone’s inability to pay fines, fees, or restitution. Probation can be extended for up to two years to enable someone to complete probation terms. Lastly, the legislation required that probation officers submit a compliance report when requested by the court, or when the Louisiana Division of Probation and Parole requests that the court make a determination with respect to earned compliance credits, modification, or termination of supervision.

Using data from the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections, this analysis includes data about people on probation from 2013 through 2019 with an admission reason of “new commitment.” We limited the analysis to data on people admitted for new convictions because people admitted for other reasons (e.g., interstate transfer) would not have been subject to the new sentencing guidelines. For the purposes of this analysis, eligibility is defined as a probation sentence for a nonviolent and nonsex offense. Owing to data limitations, this definition of eligibility is not limited to first, second, and third convictions.

This data analysis was limited in a few ways. Risk assessment and criminal-history information was not available for enough cases to use, and recidivism data were not available. The policy has only been in effect since late 2017, limiting the amount of time available for an analysis of time served on supervision and supervision outcomes. Because other policy changes were implemented over the same period, it was not possible to isolate the impacts of the probation sentencing limit.

In addition, Urban and CJI sought to better understand factors that may be influencing the implementation of this policy that may not be immediately recognized through data analysis alone. To do this, we thoroughly reviewed state statutes, policies, and documents related to those policies. We also interviewed judges, probation staff, supervisors, and administrators, focusing on speaking with people from a cross-section of rural and urban areas in each of Louisiana’s three supervision regions. For more information on the data and methodology, see the technical appendix.

During the analysis period (2013 through 2019), Louisiana’s probation population continued to decline, falling from 33,012 in 2013 to 31,412 in 2016 (before sentencing reform) and then to 26,090 in 2019. Probation starts declined from 2013 to 2016 but then increased slightly by 2019, though they remained below 2013 levels. Most people on probation in Louisiana are convicted of drug or property offenses, and well over 85 percent of the total probation population is eligible for the maximum three-year probation sentence.

Urban and CJI explored the state’s implementation of the probation sentencing reform and its impact on the supervised population, and we compared the outcomes of people who received the new probation maximum compared with the outcomes of those who did not. The key research questions for Louisiana are the following:

- How has the reform affected imposed probation sentences?

- What is the distribution of probation sentence lengths issued for people convicted of eligible crimes postreform, and how does that compare with sentencing prereform?

- Has reducing the maximum probation sentence affected sentencing across the whole probation population, including people sentenced for noneligible offenses? How?

- How has the reform been implemented?

- Have probation sentence lengths varied by race/ethnicity, gender, or age? Have these patterns changed since reform?

- Are any differences evident in how similarly situated people (e.g., by offense, risk level) are sentenced across parishes?

- How has the reform affected preliminary outcomes for eligible people?

- Since implementation, has there been any change in the rate of revocations among people impacted by the reform?

Findings on Probation Sentencing Reform in Louisiana

Probation Sentence Lengths Declined Postreform

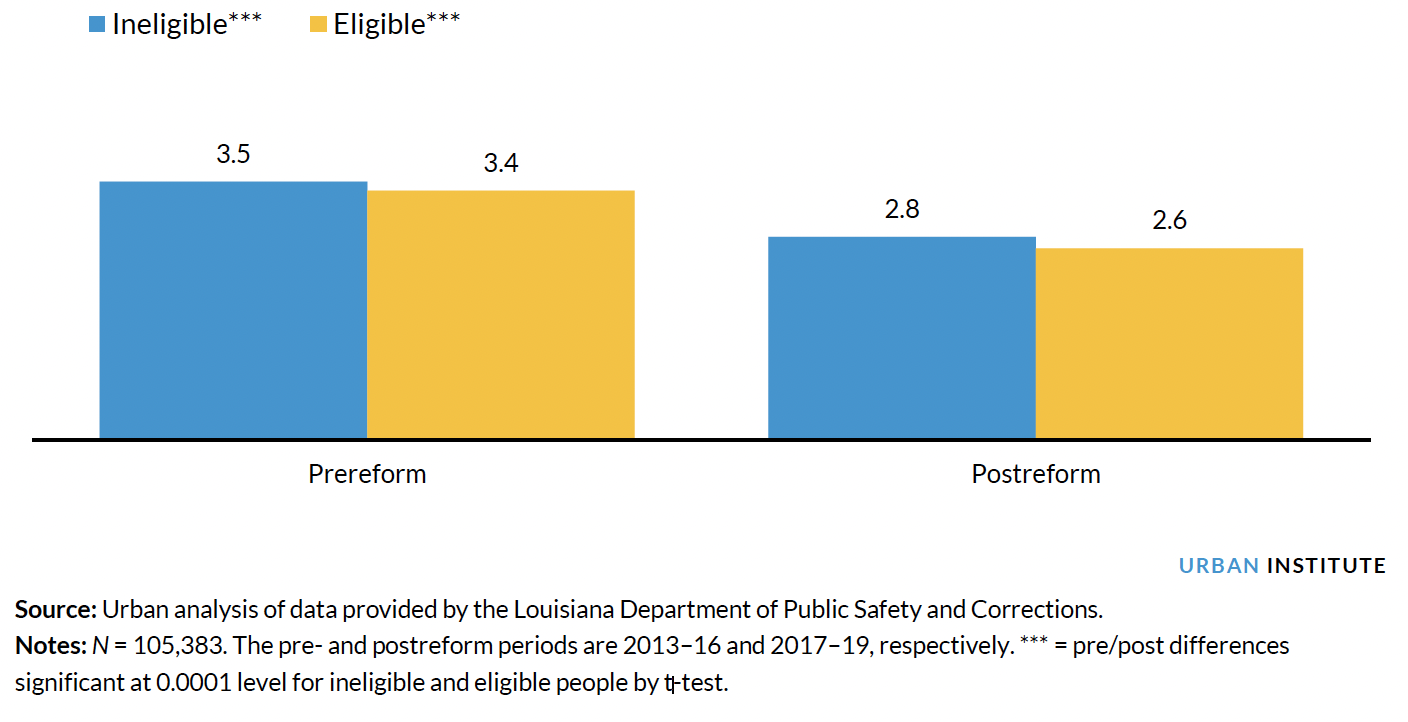

Among people defined as eligible for this analysis (people on probation for a nonviolent and nonsex offense from 2013 to 2019), the average probation sentence given fell from 3.4 years before the probation sentencing reform to 2.6 years after the reform took effect (figure 1). The same decline in the lengths of probation sentences postreform is seen across all offense types. Sentences fell from 3.3 to 2.7 years for drug offenses and from 3.4 to 2.5 years for property offenses.

Figure 1: Average Probation Sentence (in Years) by Eligibility in Louisiana before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform

Interestingly, the average probation sentences given to people not eligible for the three-year maximum sentence also declined during the postreform period. This is also true for sentences for violent offenses (down eight months) and sex offenses (down nine months).

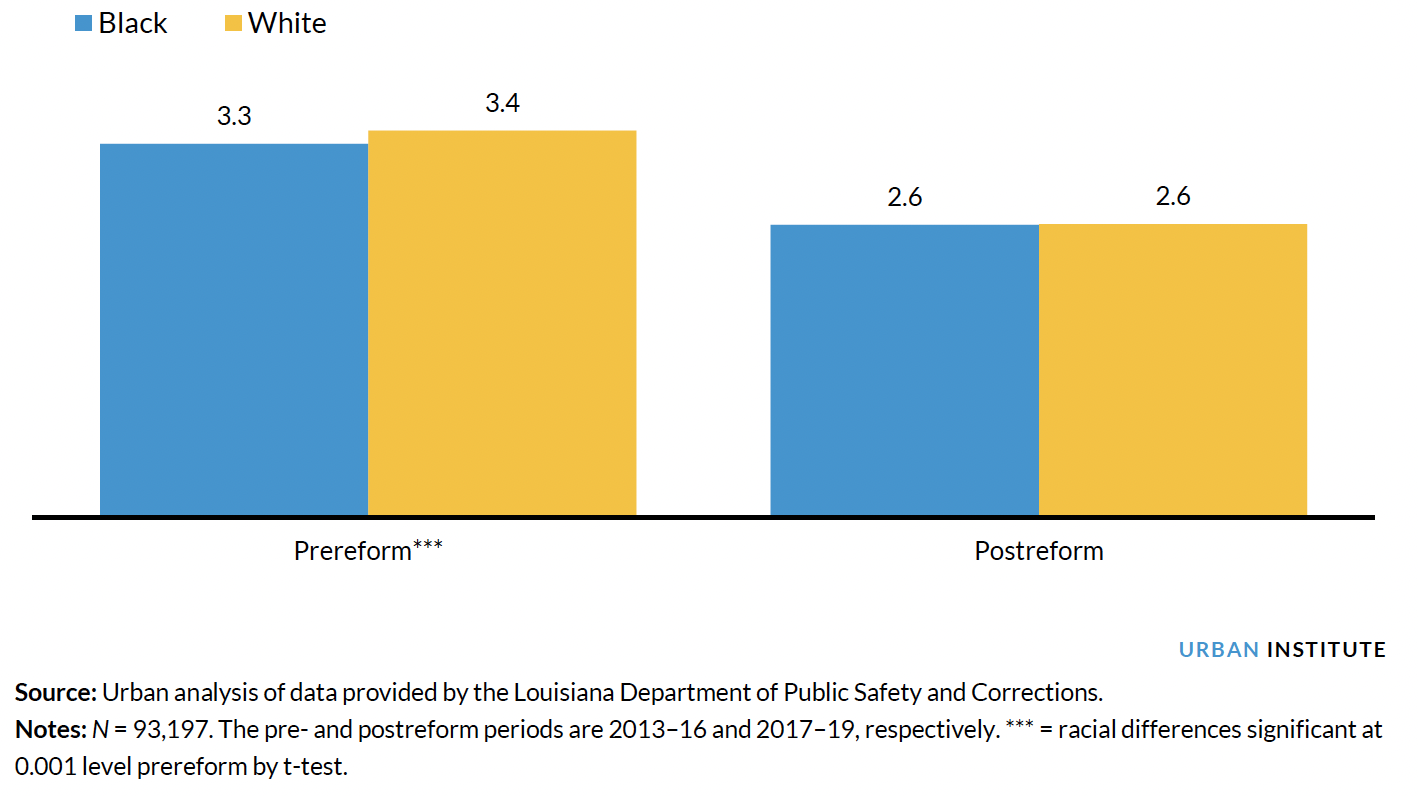

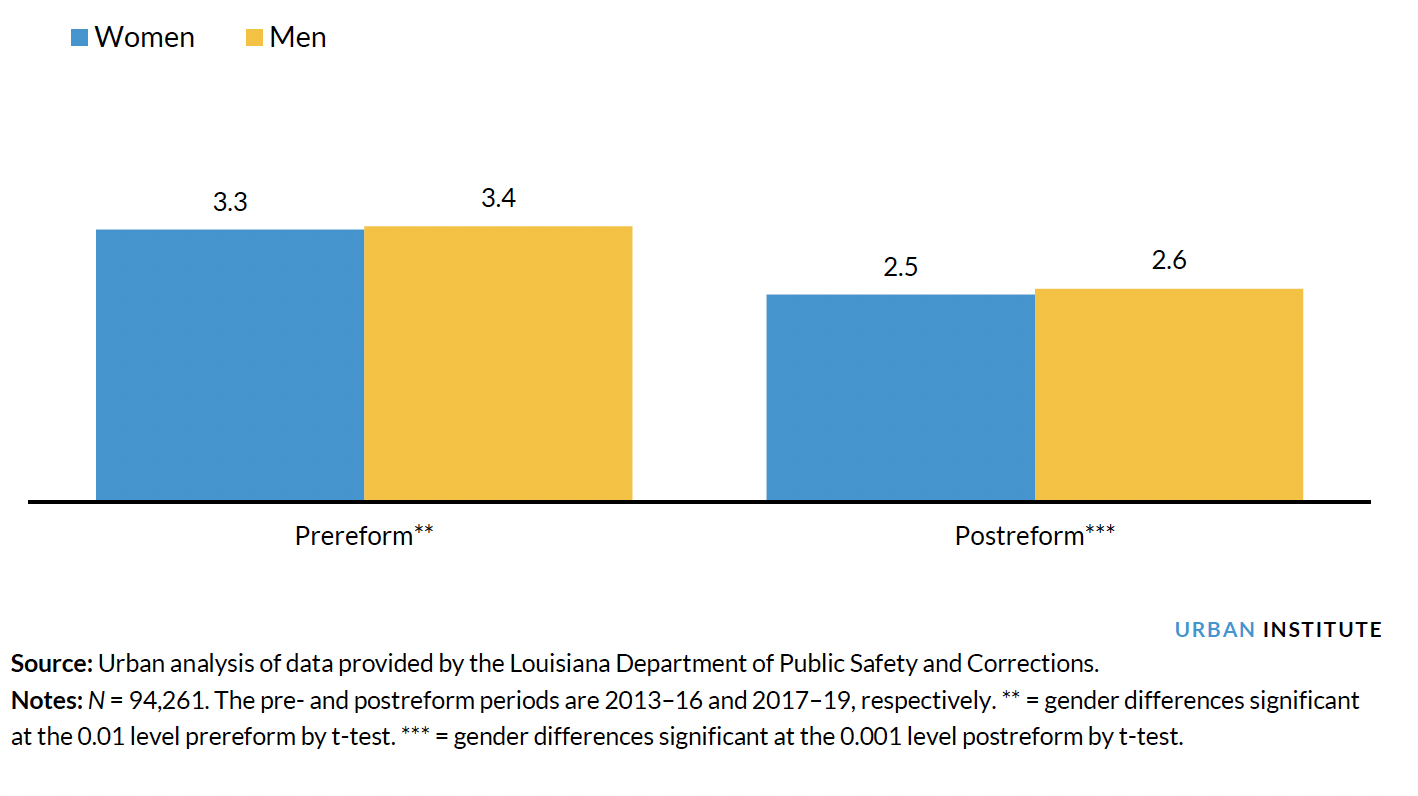

Black people were given slightly shorter sentences than white people before reform, and probation sentence lengths were shorter for both groups postreform (figure 2). Moreover, women were given slightly shorter probation sentences (3.3 years) than men (3.4 years) before the reform. Sentences for both groups were shorter postreform, and women were still given slightly shorter sentences.

Figure 2: Average Probation Sentence (in Years) among Black and White People in Louisiana before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform

Figure 3: Average Probation Sentence (in Years) by Gender in Louisiana before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform

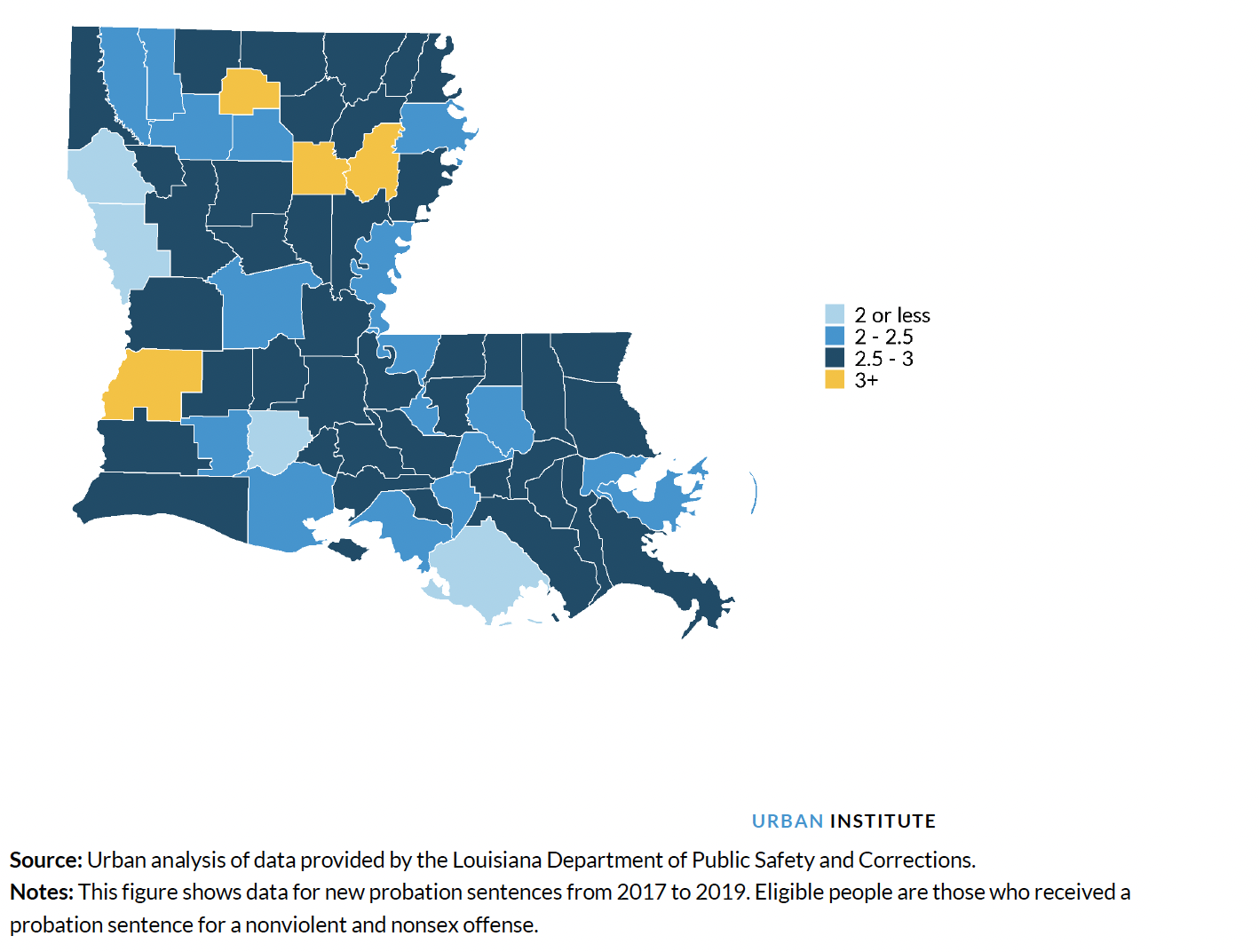

Although there is some geographic variation in average probation sentences given in the post-reform period, all but four Louisiana parishes have average probation sentence lengths under three years for eligible offense types.

Figure 4: Average Probation Sentence Length (in Years) in Louisiana after 2017 Sentencing Reform among Eligible People by Parish

Determining Impact on Time Served Is Complicated, and Perceptions of the Reform Are Mixed

Louisiana’s probation sentencing reform was signed into law in 2017. The data that the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections provided for this study included new probation commitments between 2013 and 2019; therefore, given the average probation sentence in Louisiana is 2.6 years, insufficient time has elapsed to determine how the three-year cap on probation sentences is related to actual time served on probation.

The other factor affecting our analysis of actual time served is that changes in actual time served on probation postreform cannot be attributed solely to the sentencing reform. While the reform was being enacted and implemented, Louisiana was also implementing a policy allowing people on probation to earn compliance credits, which allow people to earn 30 days off their probation sentences for every full calendar month that they comply with their supervision conditions. People who comply with those conditions may reduce their probation terms by up to one-half. Once someone satisfies their full supervision term through a combination of time served and time credited for compliance, they can be discharged from supervision.

Probation administrators and staff we interviewed indicated that the reduced maximum sentence was not initially seen as a policy that significantly impacted probation officers, because they do not make sentencing decisions. Instead, the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections focused attention and training on other 2017 reforms that would impact daily supervision practices. What did impact probation officers was the potential combined effect of shortened probation sentences and earned compliance credits. Although most probation staff consider this combination a benefit for their caseloads and an incentive for people on probation, some are concerned that the reduced probation terms postreform have given some people on probation insufficient time to complete their programming requirements, pay their restitution, and “change their mindsets,” as one staff member put it. Others believe this indicates not that postreform probation terms have been too short, but rather that programming requirements and restitution obligations have been too onerous and should be reduced so they can reasonably be completed during the shorter sentences.

In 2018, Louisiana passed Senate Bill 389, allowing probation sentences to be extended by up to two years to allow people to complete probation conditions. Probation staff reported that probation terms are being extended for this purpose. Senate Bill 389 prohibited revoking or extending someone’s probation term solely because they cannot pay fines, fees, or restitution to victims; instead, any remaining restitution owed is to be transferred to a civil judgment. Nonetheless, probation staff reported that there continue to be cases in which people’s probation terms are extended solely to allow for payment of financial obligations. They indicated that the court has held some people on supervision by repeatedly continuing motions for revocation until enough time has passed for them to pay, whereupon it has dismissed the motions.

Although leaders from the Department of Public Safety and Corrections report that the sentencing reform and earned compliance credit policies have reduced probation officers’ average allocated caseloads, some probation staff indicated they have not realized these benefits because of extra work associated with early discharge due to earned compliance credits. Senate Bill 389 modified the earned compliance credit policy to require judicial approval for release from supervision resulting from earned compliance credits. This led to judge-specific practices that create extra work for officers. Some judges want to be notified via letter in advance of people’s earned compliance discharge dates and actively grant approval for discharge, whereas other judges do not want to be notified. Officers must maintain awareness of which court a person’s case is in, and whether a particular judge requires approval before release. This is especially difficult for any case that originates in a parish or region other than the one the person is being supervised in, as officers are less familiar with the preferences of judges in other jurisdictions.

Judges also hold mixed views of the probation sentencing reform and earned compliance credit policies. While some support the goal of reducing the amount of time people spend on probation, some feel these policies have limited their ability to tailor sentences to individual cases, including the ability to apply longer sentences so people have more time to engage in and complete treatment. Together, the probation sentencing reform and the earned compliance credits allow for 18-month supervision periods; this, in part, prompted the 2018 change requiring judicial approval of release.

After Reform, Revocation Rates Decreased and Success Rates Increased

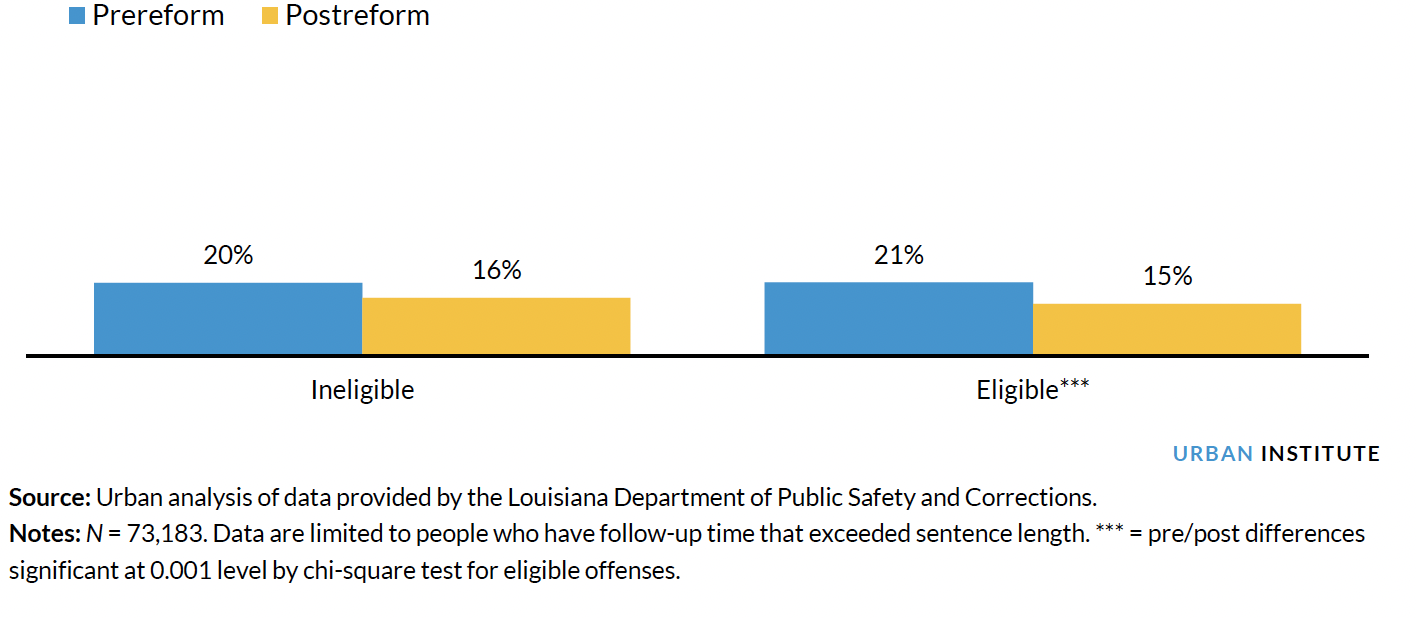

Among people eligible for the three-year maximum probation sentence, revocation rates decreased. Revocation rates also decreased for people with sentences for violent and sex offenses who were not eligible for the three-year maximum sentence (figure 5).

Figure 5: Rates of Probation Revocation in Louisiana before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform among People Eligible and Ineligible for the Three-Year Maximum Sentence

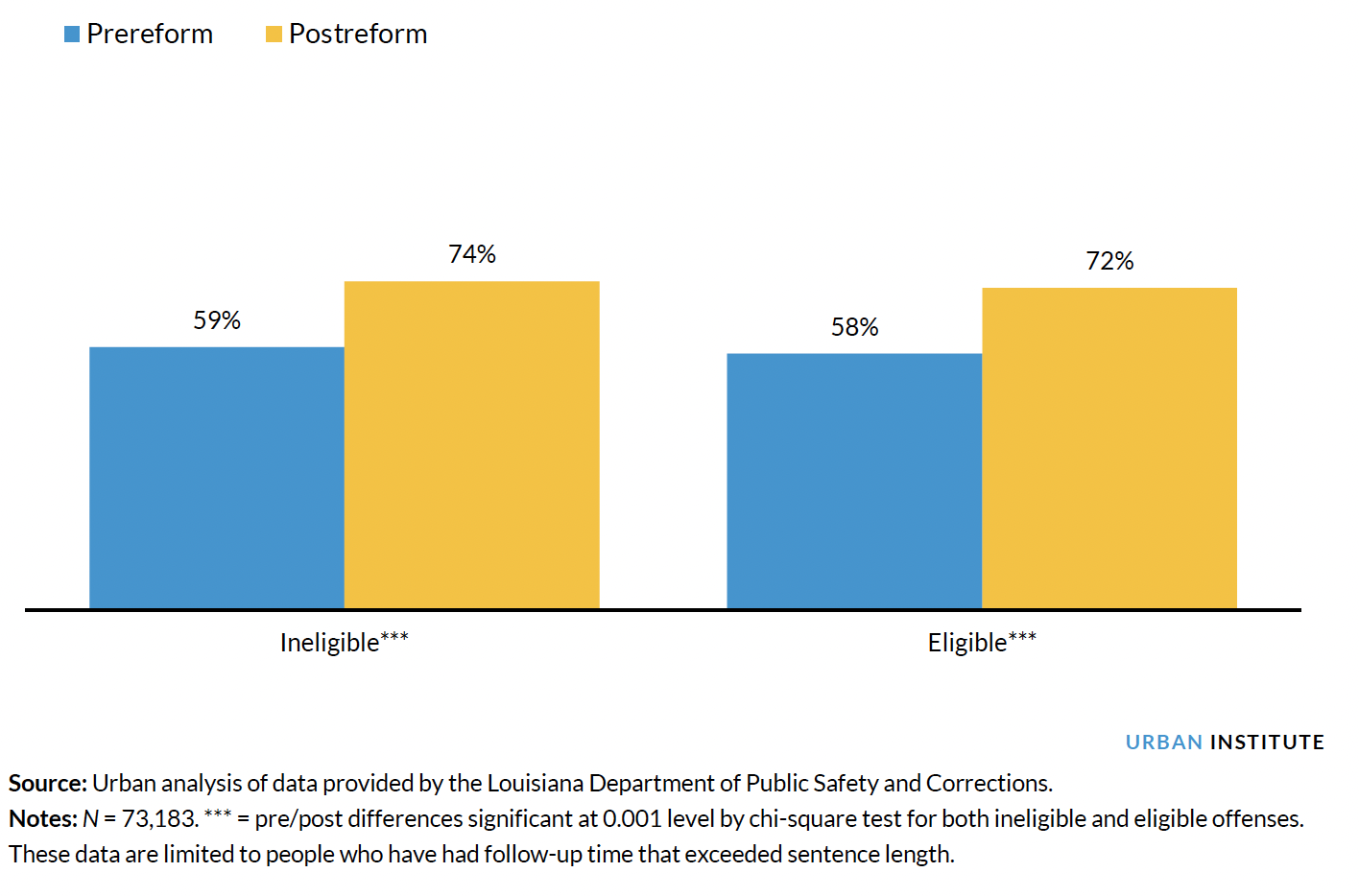

There are various means by which probation can end in Louisiana, including earned compliance credits, early termination, sentence expiration, revocation, and unsuccessful completion not ending in revocation. Earned compliance closure, early termination, and expiration are categorized as successful completions. Among people on probation for nonviolent, nonsex offenses, the rate of successful completion rose from 58 percent before the 2017 reforms to 72 percent after the reforms. Successful completions also rose for people on probation for violent and/or sex offenses (figure 6).

Figure 6: Rates of Successful Probation Completion in Louisiana before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform for People Eligible and Ineligible for the Three-Year Maximum Sentence

Georgia

In 2017, Georgia passed Senate Bill 174, which was intended to modify the length of probation terms through three policies: behavioral incentive dates, early termination petitions, and active supervision caps. This analysis focuses on the first two policies, as the third does not result in a person being discharged from supervision.

Starting July 1, 2017, all people newly sentenced to felony probation—that is, people receiving first-time felony convictions without prison time—were required to be assigned BIDs at sentencing not to exceed three years from their sentencing dates. The Georgia Department of Community Supervision petitions the court with an order to terminate supervision at that new discharge date as long as the person is in compliance with all probation conditions, has paid all restitution, and has no arrests for anything other than a minor traffic offense.

Senate Bill 174 also required DCS to file an early termination petition with the court for anyone who has completed three years of supervision, has not been arrested for anything other than a minor traffic offense, has complied with probation conditions, and has paid all restitution. The people eligible for early termination are those convicted of nonviolent felony offenses and sentenced to three years or more with no revocations. This policy was made retroactive.

Our analysis found that

- judges have given few BIDs at sentencing,

- DCS and judges have approved few of the BIDs that judges have given at sentencing,

- many people may be eligible for early probation termination in Georgia, but few receive it,

- more cases have been placed on unsupervised supervision than have been discharged through BIDs or early termination, and

- violations and sanctions are down postreform.

Background on Probation Sentencing Reform in Georgia

Georgia has engaged in several comprehensive justice-reform efforts. Most recently, a 2016 analysis of community supervision in the state found that it had the highest felony probation rate in the country, with nearly 206,000 people on felony probation. Caseloads for officers with medium- and high-risk caseloads were around 130 people per officer. The average probation sentence length for felony probation was 5.0 years for a direct sentence and 7.5 years for a split sentence (whereby a person is convicted and sentenced to serve a custodial term followed by probation). Data analysis revealed that revocations from community supervision continued to contribute to the prison population, as more than half of prison admissions were likely probation revocations for new offenses or violations of special conditions (Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform 2017).

In 2017, the state passed Senate Bill 174 as part of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative. It included community supervision provisions aimed at reducing recidivism and lengthy probation sentences, incentivizing compliance with conditions, and improving the handling of legal financial obligations. The following three policies were intended to reduce the time people spend on supervision:

- As of July 1, 2017, everyone newly sentenced to felony probation—meaning everyone receiving a first-time felony conviction without a split sentence—is, according to statute, to be assigned a BID at sentencing, and the BID may not exceed three years from the sentencing date. DCS is to provide the court with an order to terminate supervision on that new discharge date as long as the person is in compliance with all probation conditions, has paid all restitution, and has no arrests for anything other than a minor traffic offense.

- For early termination, DCS is required to file a written report with the court for anyone who has completed three years of supervision. If the person has not been arrested for anything other than a minor traffic offense, has complied with probation conditions, and has paid all restitution, DCS must petition the court to terminate probation. To be eligible for early termination, someone must have been convicted of a nonviolent felony offense and sentenced to three years or more with no prior revocations. Because this policy was retroactive, people on probation before July 1, 2017, who met these conditions were also made eligible for this type of release.

- For most felony probation cases in Georgia, reporting supervision is limited to two years. If someone’s restitution is paid in full and they have not been convicted of criminal gang activity, they are to be transferred to unsupervised supervision for the remainder of their term. Additionally, Georgia has a status of administrative supervision which is also a type of nonreporting supervision. Unlike unsupervised supervision, however, in administrative supervision, the supervision officer cannot move the person being supervised to other supervision types if a violation occurs.

Using data from the Georgia Department of Community Supervision, our analysis includes data about people on probation supervision from 2017 through 2020. The data include information about more than 340,000 unique individuals, more than 358,000 unique supervision terms, and more than 492,000 unique dockets. Each docket is the individual sentence that a person on supervision has. Each person and each supervision term can have multiple dockets. We conducted this analysis at the docket level to better understand the specific sentences that are getting BIDs. But this means that we do not report on the closures of supervision terms resulting from BIDs. Data provided from DCS allow for reporting on supervision closures, and future analyses could include this component. In this report, we only report on the closures of particular sentences within a supervision term that have been terminated through BIDs. Further, because the data are available from January 2017 onwards, most of our analysis is limited to people who started probation in January 2017 or later. In general, the prereform period includes people sentenced from January 2017 through June 2017. The postreform period includes people sentenced from July 2017 through December 2020.

For the purposes of this analysis, someone is defined as eligible to have received a BID at sentencing if they received a straight felony probation sentence for the first time after the reform took effect in July 2017. Our analysis cannot accurately assess how many people have been eligible to be approved to have their sentences closed at the time of their BIDs because our definition of eligibility does not factor in the behavioral criteria required by statute, including compliance with probation conditions and full payment of restitution. We define someone as eligible for early termination if they were convicted of an offense other than a person or sex offense, they received a sentence of at least three years, and they served at least three years. As with BIDs, however, this definition does not account for the behavioral criteria used by DCS to determine whether someone should be discharged via early termination, including compliance with probation conditions, no arrests while on probation, and full payment of restitution.

In addition to the quantitative data from DCS, the CJI and Urban team conducted focus groups with probation leadership and staff in six judicial circuits across Georgia, representing counties of various sizes. Focus group participants included community supervision chiefs, assistant chiefs, supervisors, community supervision officers, court specialists, and administrative staff. We also interviewed judges from two judicial circuits in the state.

In exploring the implementation of Georgia’s probation sentencing reform, our key research questions were the following:

- How has the reform affected probation sentences imposed?

- How has the reform been implemented?

- How has the reform affected preliminary outcomes for eligible people?

Background Data on Sentence Length

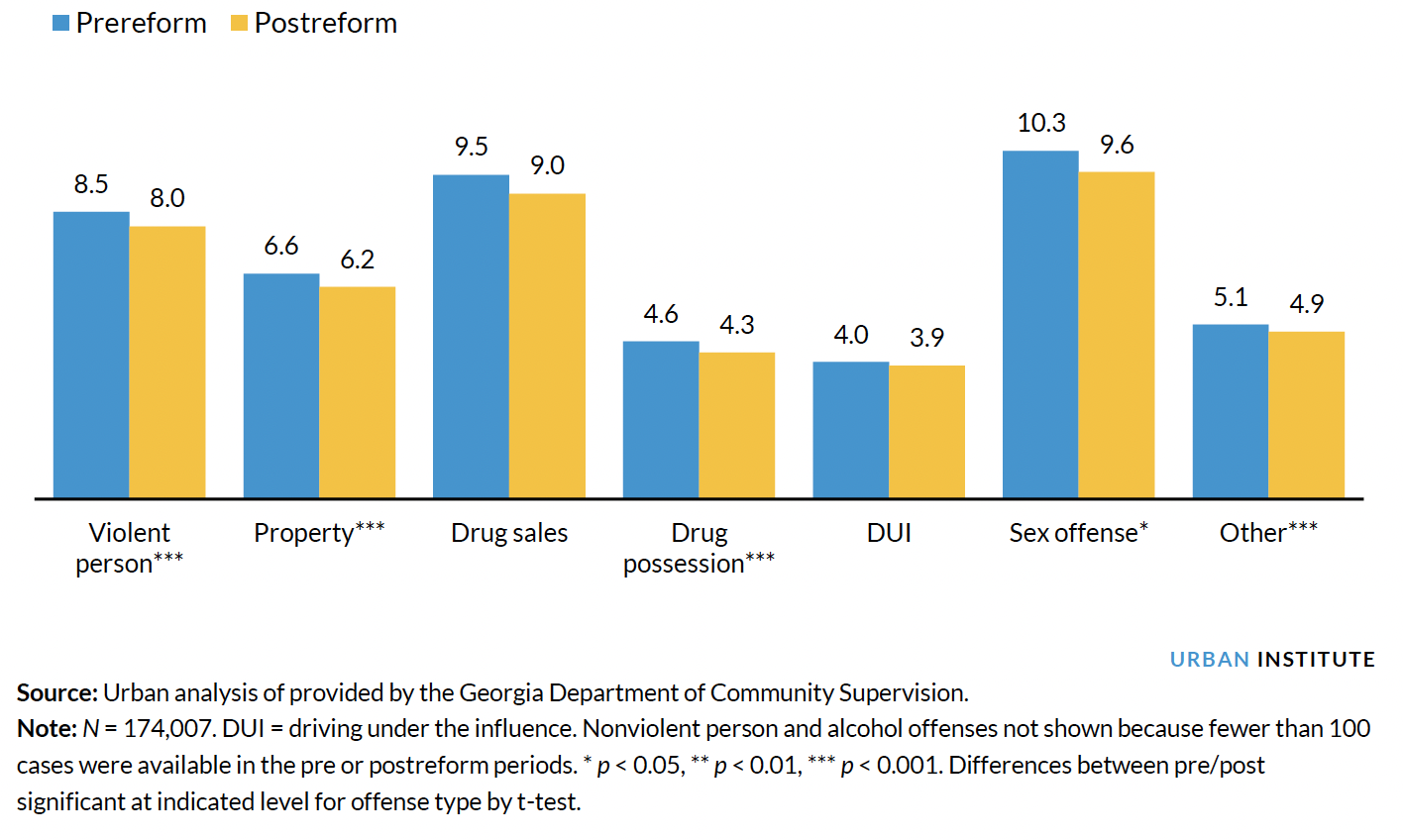

In the period we examined, as policymakers in Georgia reviewed data and passed legislation to reduce the size of the supervision population, overall system shifts began to occur. Although the policies examined did not directly require shorter felony probation sentence lengths, data show that these average sentence lengths did shift during the implementation period. Specifically, from 2017 through 2020, the average felony probation sentence declined from 6.0 to 5.6 years. A similar decline occurred for people who are Black, white, female, and male. The average sentence length also decreased across all offense types (figure 7).

Figure 7: Average Felony Probation Sentence (in Years) in Georgia before and after 2017 Sentencing Reform, by Offense Type

Findings on Probation Sentencing Reform in Georgia

After Reform, Judges Gave Few Behavioral Incentive Dates at Sentencing

Roughly a third of the felony probation population was eligible for BIDs after the 2017 reform. Of the 127,159 felony probation dockets sentenced from July 2017 through December 2020, 40,134 were eligible for a BID at sentencing, but only 6,949 dockets (17 percent of eligible dockets) actually received a BID from a judge at sentencing. In the period we analyzed, Georgia law required that a BID be given for every first-time felony docket, but there was no mechanism for automatically assigning a BID at sentencing or otherwise ensuring that BIDs were consistently given to eligible cases; instead, BIDs had to be intentionally applied to cases by judges. Senate Bill 105, passed in 2021, addressed this by providing that in any case where the court does not impose a BID at sentencing, a BID of three years will automatically be applied. It also requires the court to set a hearing within 90 days of receiving an order to terminate through a BID.

Interviews with judges and probation staff suggest judges are failing to apply BIDs to eligible sentences for various reasons. In some jurisdictions, judges may not fully understand that BIDs are mandatory for all first-time felony cases and may not consistently remember to issue them. Probation staff in these jurisdictions reported that they often need to remind judges to give BIDs at sentencing, and noted that in some cases, defense attorneys request them. One factor that may contribute to judges’ confusion is that eligibility criteria for BIDs and early termination differ: whereas early termination applies only to certain qualifying offenses, BIDs must be given to all first-time felony cases, regardless of the offense. Judges may not be receiving adequate training to clarify these eligibility criteria and that BIDs are mandatory. Moreover, judges in some jurisdictions appear to be philosophically opposed to giving BIDs and choose not to do so. Judges in a given circuit may have different perspectives or levels of awareness about BIDs and may assign them at sentencing at different rates.

The average sentence length among the BID-eligible population was not much different from that among the whole felony probation population: BID-eligible sentences averaged 5.5 years, compared with 5.7 years for the overall felony probation population.

Our analysis suggests that BIDs could significantly reduce time served on probation if they are used consistently. We find that the median sentence for people who were given BIDs at sentencing was two years shorter than for those who were not. Expanded use of BIDs in all eligible cases could significantly reduce time served on probation and therefore the size of the overall probation population.

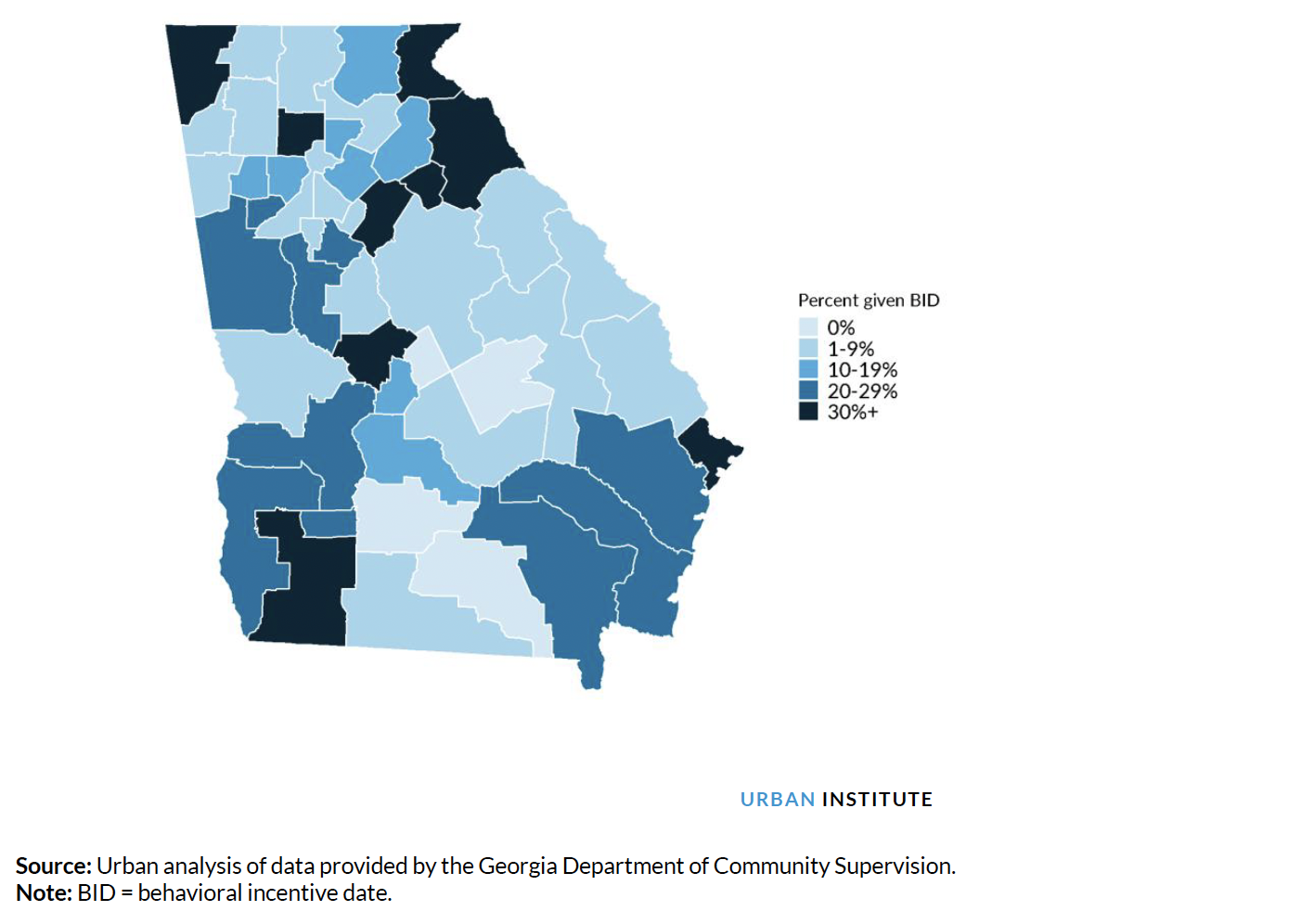

Figure 8 shows the share of dockets given BIDs at sentencing among the eligible population by judicial circuit. Among cases eligible for BIDs, issuance varied considerably by circuit, from 0 percent in the Alapaha, Dublin, and Tifton Judicial Circuits to more than 60 percent in the Northern Judicial Circuit. Again, this variation is driven by the decisions of individual judges. There is not much variation among circuits by offense types or demographic characteristics: for most offense types and for Black, white, male, and female subgroups, just under 20 percent of eligible dockets got BIDs.

Figure 8: Percentage of Dockets Given BIDs at Sentencing among Eligible Population in Georgia by Judicial Circuit of Conviction, July 2017 through December 2020

Even When Judges Give Behavioral Incentive Dates, DCS and Judges Approve Few Bid Petitions

Three months before someone’s BID, a DCS supervision officer is prompted to review their case to determine whether the discharge criteria have been met. If the person has met all criteria required to be considered for discharge, the officer prepares a BID petition. A supervisor will either approve the petition and return it to the officer for submission to the judge or will determine that it needs revision by the officer before submission. Notably, because Senate Bill 174 has only been in effect since July 2017, many of the people who have been given BIDs at sentencing have not reached those dates, and thus have not had the opportunity to be considered for release under this policy.

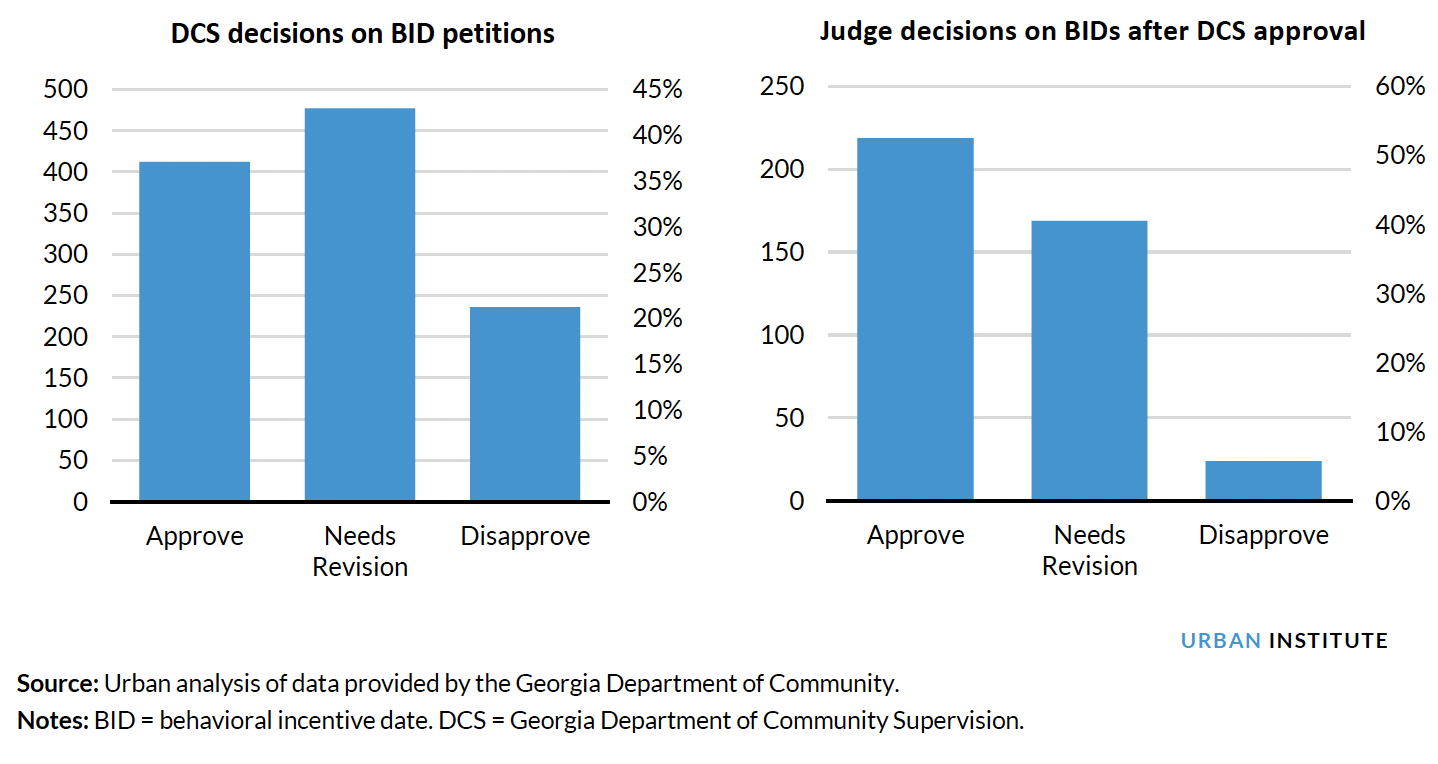

Of the BIDs that have been given at sentencing (6,949), 16 percent (1,125) have had a BID petition prepared by a DCS officer. Of those 1,125, only 412 (37 percent) have had their BID petition approved by DCS for submission to a judge. And of those 412 petitions that have been submitted to a judge, 219 (53 percent) have been approved by the judge for release.5 Notably, our analysis cannot account for whether these people have met all the criteria required for BID approval, including compliance with probation conditions and full payment of restitution, and thus whether they are actually eligible to have their sentences closed.

Figure 9 shows that many of the BID petitions that DCS has not approved for release are awaiting revision by supervision officers before they are submitted to judge. Once judges receive petitions that DCS has approved, 53 percent are approved.

Figure 9: Status of BID Petitions by the Georgia Department of Community Supervision and Submitted to Judges, July 2017 through December 2020

Although we could not fully examine compliance with supervision conditions, we can report rates of violations and sanctions during people’s supervision terms. As expected, people whose BIDs are approved by both DCS and by judges have lower rates of violations and sanctions than people whose BIDs are not approved. Twenty-one percent of people who had their BID petitions approved had sanctions during their terms, whereas 36 percent of people who did not have their BID petitions approved had sanctions. Generally, violations and sanctions are related to instances of noncompliance, so one would expect that cases with fewer instances of noncompliance would be more likely to have BID petitions approved, in line with the policy.

Given how infrequently BIDs are given at sentencing, as well as the limited time that has passed since reform, it was not feasible to broadly assess how DCS staff use BIDs. At this time, BIDs are rarely available as a discharge option, so further research will be needed to assess how DCS staff use BIDs as they become more widely available through Senate Bill 105.

Many People Are Eligible for Early Termination, but Few Receive It

Early termination could apply to the vast majority of felony probation cases—not only those sentenced after Senate Bill 174’s implementation date, but all existing felony probation cases for qualifying offenses as of July 2017. Based on the available DCS data, our analysis found 218,188 dockets since 2017 that may have been eligible for early termination. For the purposes of this analysis, in which we used a simplified definition of eligibility for early termination, a docket is considered eligible for early termination if the offense is not a person or sex offense, the sentence is at least three years, and the person had served at least three years as of January 2021. This definition of eligibility is not limited to first, second, and third felony convictions and accounts for neither prior probation revocations nor the behavioral criteria DCS uses to determine whether someone should be discharged via early termination (these criteria are compliance with probation conditions and full payment of restitution). Roughly half of eligible dockets (107,806) have received early termination petitions. An early termination petition is automatically submitted by DCS when someone has not been arrested for anything other than a minor traffic offense, does not have a revocation, and has paid all restitution. In one-quarter of those cases (28,947), DCS has approved the early termination petition, and 12,261 of those have been approved by a judge.

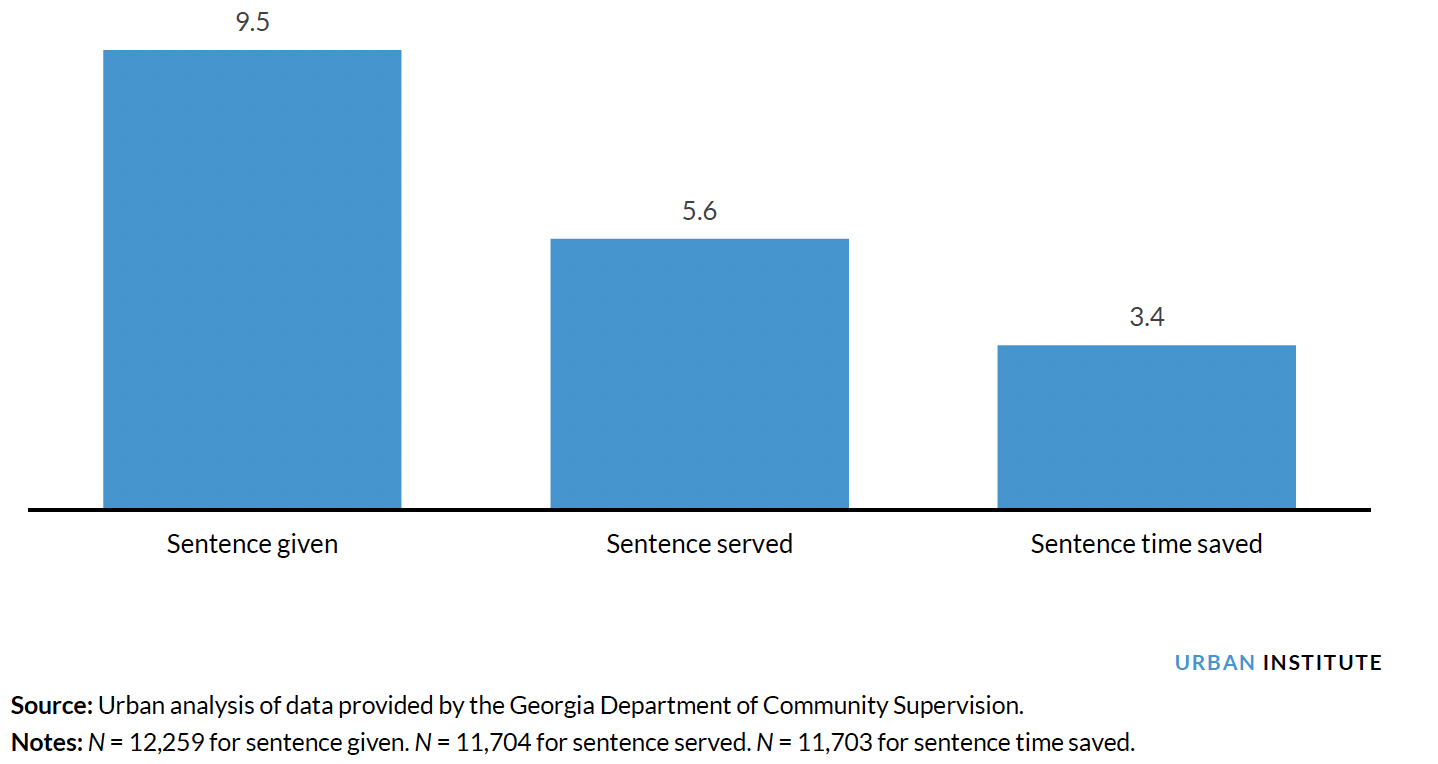

Figure 10 shows that receiving early termination in Georgia greatly reduces time on supervision. For people who have been granted early termination, the average sentence is 9.5 years, and the average time served before early termination is 5.6 years, resulting in 3.4 years of probation time saved.

Figure 10: Average Probation Sentence Length, Average Sentence Served, and Average Time Saved (in Years) off Sentence among People Granted Early Termination in Georgia, July 2017 through December 2020

Similar to cases with BID petitions, among cases with early termination petitions, cases for which petitions are approved by both DCS and a judge have lower rates of sanctions and violations than those for which petitions are not approved. For example, 12 percent of cases approved for early termination have had a sanction, compared with 36 percent of cases not approved for early termination. Again, this is somewhat expected because compliance with probation conditions is among the eligibility criteria for early termination, and sanctions and violations are often related to instances of noncompliance.

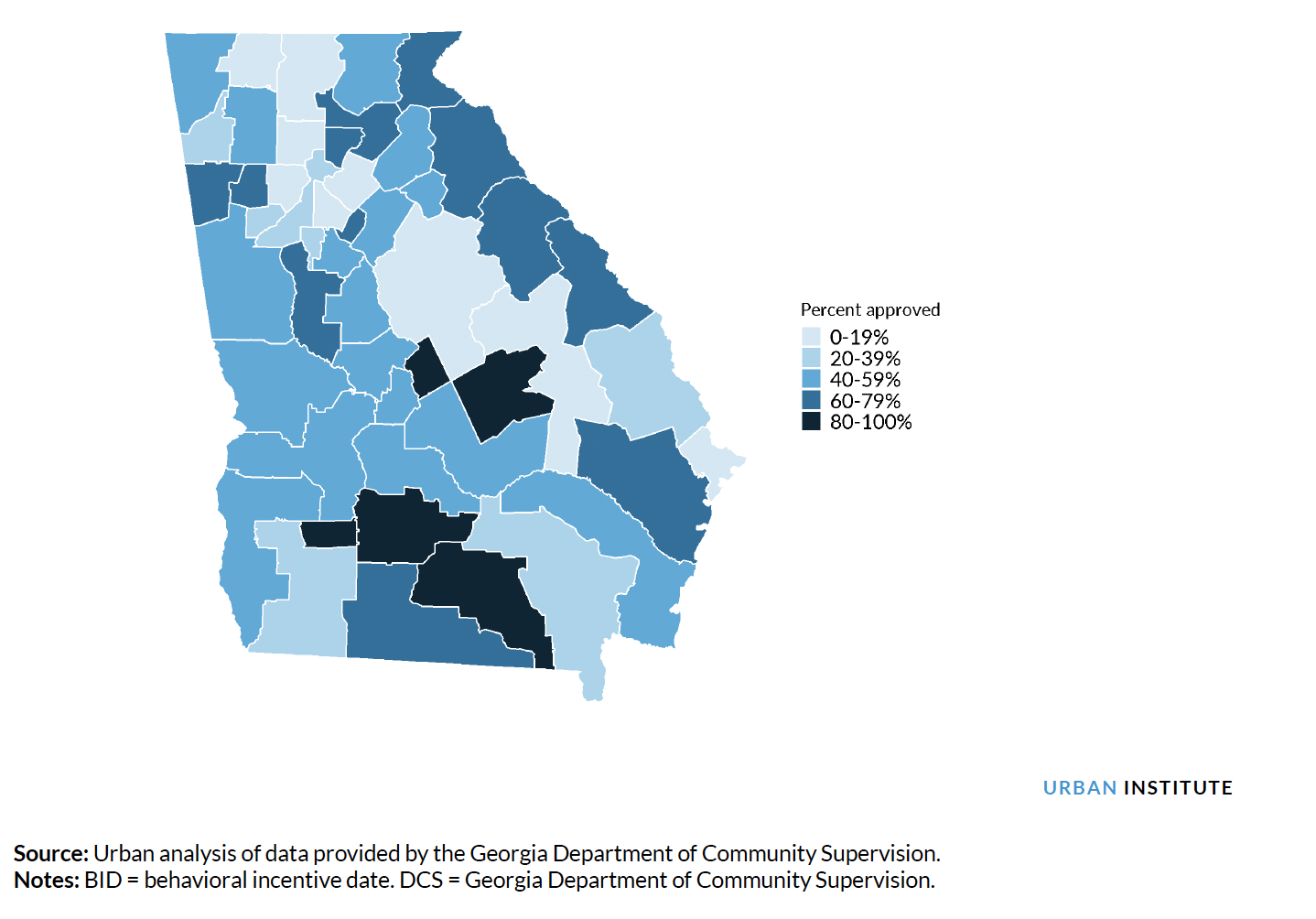

Importantly, rates of final approval for BID petitions and early termination petitions vary substantially by judicial circuit. Figure 11 shows DCS and judges have approved between 0 and 19 percent of petitions in some circuits and between 80 and 100 percent in others.

Figure 11: Percentage of Petitions for BIDs and Early Termination Approved by Judges after DCS Approval by Judicial Circuit of Conviction, July 2017 through December 2020

During the period of analysis, early termination was used much more frequently than BIDs, largely because the process for being considered for early termination was driven by automated DCS processes rather than judicial decisionmaking. But early termination is still underused: only 27 percent of early termination petitions have been approved by DCS, and only 42 percent of those approved petitions have then been approved by judges and discharged.

By law, judges have the discretion to approve or deny early termination petitions for any reason (“for the best interest of justice and the welfare of society,” per Senate Bill 1746), and judges in some circuits regularly use their discretion to deny petitions. In fact, judges in some circuits have established local policies dictating circumstances in which cases are automatically considered ineligible for early termination beyond the statutory criteria. This may include requiring a person to have paid all fines and fees (in addition to restitution) in full, that they only have a certain number of years remaining on their sentence, or that they have not failed any drug tests during their probation term.

Some probation officers we interviewed noted that the automated process through which they submit early termination petitions to the court means they regularly submit petitions they believe judges in their circuits are likely to deny. This underscores that judicial discretion may limit the efficiency and effectiveness of Georgia’s early termination policy. Nonetheless, the automated system for identifying cases eligible for early termination makes it much easier for DCS staff to process them and submit petitions for early discharge than it would be if staff had to do so manually. Still, people with multiple felony cases may receive early termination on one docket but remain on supervision for others.

Because judges in Georgia have broad discretion to deny early termination petitions, these petitions may not be effective incentives for people on probation. One judge we interviewed noted that people may accept a longer probation sentence as part of their plea negotiations based on the assumption that they will be eligible for early termination at three years in circuits where early termination is actually unlikely because of judges’ local policies or individual preferences.

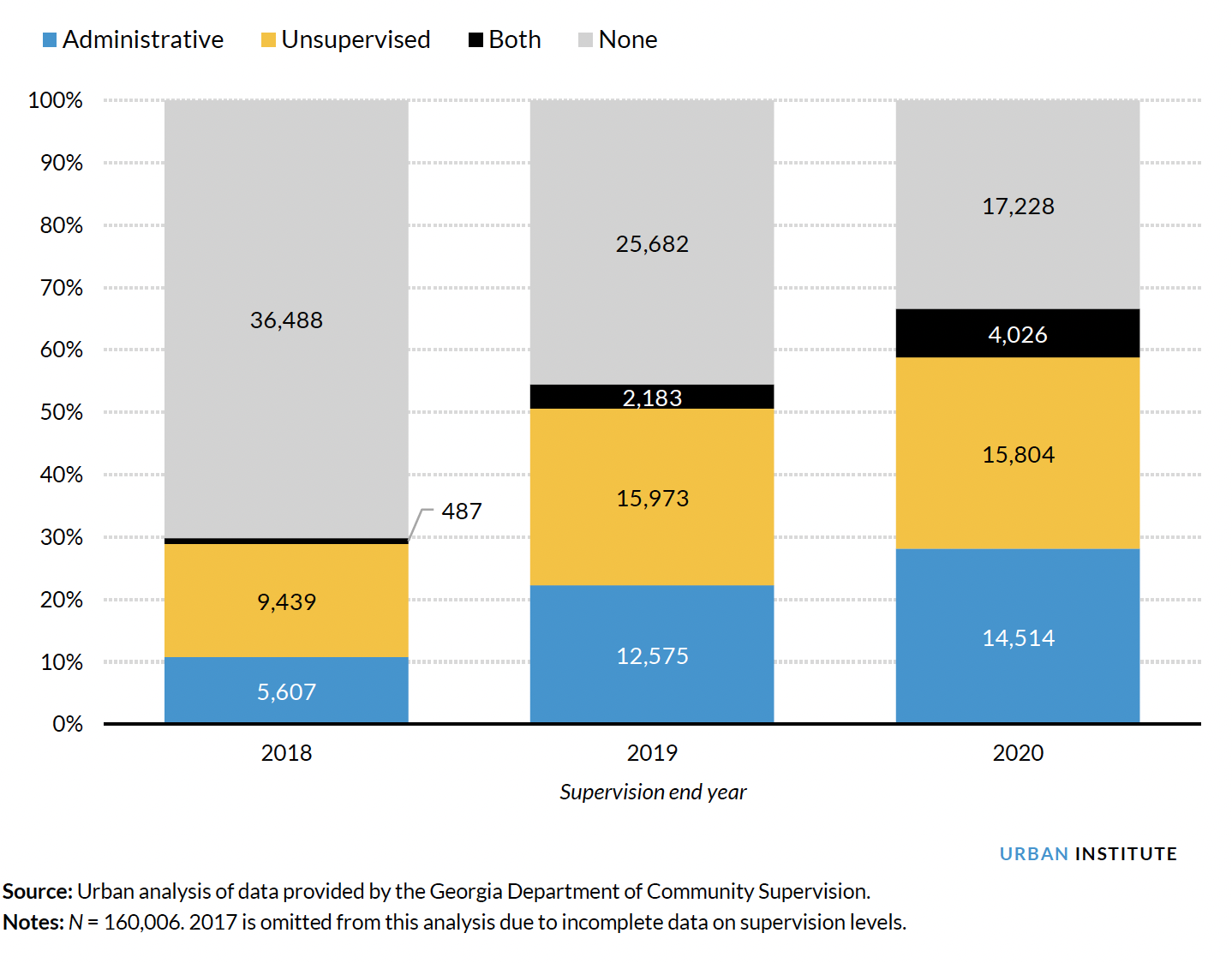

More Probation Cases Have Been Placed on Unsupervised Supervision Than Have Been Discharged through Behavioral Incentive Dates or Early Termination

As noted above, we analyzed the total number of probation cases (or dockets) in Georgia and not individual supervision terms or people. Notably, someone may have multiple cases or dockets open at the same time. Total cases at year-end declined from 2017 through 2020 by roughly 13 percent, and in 2020 totaled just over 282,000.

When examining how many cases have been impacted by Senate Bill 174, we find that many probation cases in Georgia have been placed on unsupervised probation at some point since 2018, whereas fewer have received BID discharges or early terminations. Of the cases that ended in 2020, 19,830 (38 percent) were on unsupervised status at some point in their term (figure 12), whereas just under 12,000 were closed through BID discharge or early termination from July 2017 through December 2020 (roughly 6 percent of all cases closed during this period).

Figure 12: Number of Probation Cases That Had Been on Nonreporting Supervision in Georgia by Year-End, 2018 through 2020

Even when examining only cases eligible for BIDs or early terminations, the data show that far more cases are placed on nonreporting supervision (that is cases that may be categorized as administrative, unsupervised, or both) than are closed to BID discharge or early termination. Roughly 45 percent of cases eligible for BIDs at sentencing and roughly 60 percent of cases eligible for early termination are placed on nonreporting supervision at some point during supervision.

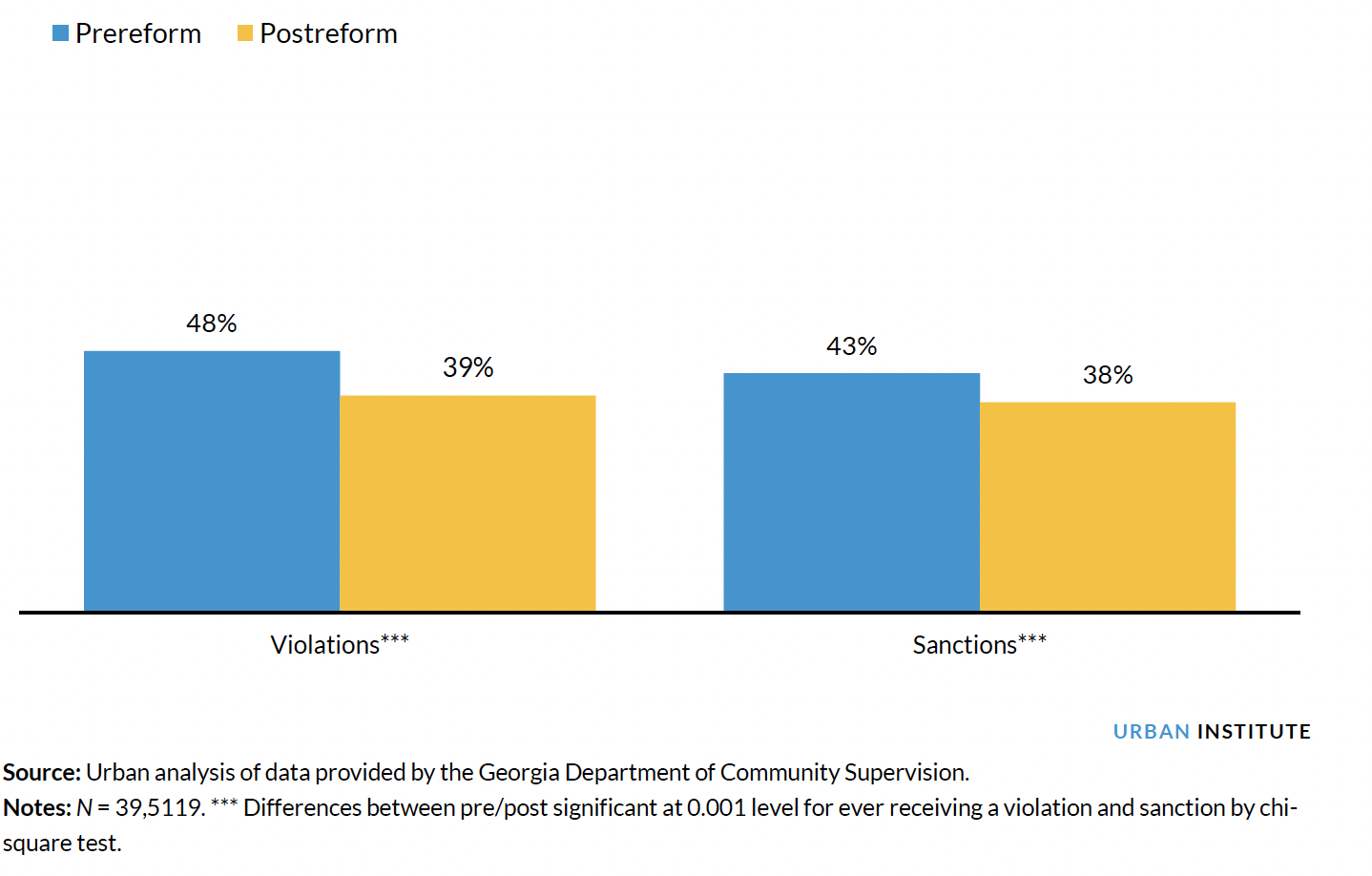

Violations and Sanctions Are Down Since Reform

The potential incentive of early termination and shorter terms of supervision might lead to fewer violations and sanctions while on supervision. The data show that since Georgia’s sentencing reforms were implemented, rates of successful supervision completion across the felony probation population have remained relatively steady at over 70 percent. But rates of violations and sanctions fell from the prereform period (January 2017 through June 2017) to the postreform period (July 2017 through December 2020).

Figure 13: Rates of Violations and Sanctions among People Who Ended Supervision in Georgia before and after July 2017 Sentencing Reforms

Conclusions and Recommendations

Louisiana and Georgia took different approaches to reforming probation sentencing through policy, but the following conclusions can be generalized from the two states based on our analysis:

- Sentence lengths among the overall probation populations have decreased in both states postreform. In Louisiana, sentences fell from an average of 3.4 years prereform to 2.6 years postreform for people eligible for the three-year maximum. In Georgia, sentences fell from an average of 6.0 years in 2017 to 5.6 years in 2019 and 2020 among all people on probation. These reductions hold across all offense types.

- Georgia has experienced challenges applying its changes to probation sentencing policy, which rely heavily on judicial discretion. During the period we analyzed, many judges failed to assign BIDs at sentencing, meaning many people on probation did not have the opportunity to be discharged under this policy; this was addressed by Senate Bill 105, passed in 2021, which automatically sets BIDs of three years in cases where judges do not assign them. But even when BIDs are given and the DCS petitions the court to close a supervision term because someone meets the eligibility criteria, judges only approve petitions half of the time. Similarly, judges approve fewer than half of DCS-approved petitions for early termination. In contrast, because Louisiana established a maximum sentence length that can be given at sentencing, discretion has not prevented the reform from being used.

- Geographic variations exist in both states because of how judges apply the policies.

- In Louisiana, rates of successful supervision completions have increased, and rates of revocation have decreased since the sentencing reforms. In Georgia, rates of successful completions have remained steady, and rates of violations and sanctions have decreased.

- Probation staff in both states generally consider the shorter probation sentences beneficial and believe the opportunity to be considered for early release is an incentive for people on their caseloads. But when there is judicial discretion, the possibility of denial by a judge reduces the effectiveness of early release as an incentive.

- Requiring financial obligations to be paid in full before supervision closure significantly reduces the impact of these reforms. Even in Louisiana, where obligations can be transferred to civil judgments, some judges choose to hold probation cases open to provide people more time to meet financial obligations.

- In both states, the combinations of policy reforms have reportedly driven reductions in probation cases. For example, cases in Louisiana are lower largely because of the combined effects of changes to probation sentencing and implementation of earned compliance credits. In many parts of Georgia, active cases are down mainly because the policy capped active supervision terms, but early termination and BID approvals have likely also affected this in some jurisdictions.

Based on our findings, we provide the following recommendations for states considering reforming their probation sentencing policies or programs:

- When developing policy, consider the interplay between policies that will be implemented simultaneously, including the impact that interplay will have on implementation. For example, Georgia adopted BIDs, early termination, and caps on active supervision in 2017. The ability to more easily shift people to unsupervised status appears to have been the most impactful aspect of that policy package, because eligibility criteria are broader for unsupervised status and some probation staff are more comfortable keeping people on unsupervised probation (“to keep our hands on them,” as one staff member put it) than discharging them fully from supervision. In Georgia, this can cause someone on community supervision to stay under correctional control for a decade or longer.

- Because Georgia gives very long probation sentences, some judges and supervision staff consider three years to be too early to discharge people from probation, particularly when sentences are 10 years or longer. In states like Georgia that give longer supervision sentences than other states, meaningful front-end reform to reduce sentence lengths is needed to make policies like BIDs and early termination designed to reduce time served on the back end more effective.

- States should review data about financial obligations and their impact on supervision lengths and look for ways to collect on these obligations that do not involve correctional control.

- States should closely monitor and report on the use and effectiveness of probation sentencing reforms so underuse and deviations from policy can be addressed and corrected.

Notes

- Jake Horowitz, “1 in 55 U.S. Adults Is on Probation or Parole,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, October 31, 2018, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2018/10/31/1-in-55-us-adults-is-on-probation-or-parole.

- The population eligible does not account for disqualifications related to supervision compliance and restitution payment (this number includes those who may otherwise be excluded due to problems with supervision compliance and making restitution payments). This calculation is based on the number of felony supervision dockets sentenced in the eligible period divided by all felony supervision dockets sentenced in the period, and not necessarily individual people.

- Georgia passed new legislation, Senate Bill 105, in 2021 that provides further guidance on BIDs and early termination processes. In addition to clarifying what it means to be in compliance with supervision requirements for the purpose of having one’s sentence closed through a BID or early termination, the new law requires the court to set a hearing within 90 days of receiving an order to terminate through a BID or early termination. It also provides that a BID date of three years from the date of sentence imposition will automatically be applied in cases where a court does not actively impose a BID date at sentencing.

- This number is based on a simplified definition of eligibility: having no person or sex offenses, having a sentence of three or more years, having served at least three years, and having the sentence end or begin postreform.

- Some additional cases were identified in the data as having had BIDs approved even though they were not identified as being eligible for BIDs (n = 106) or as having received a BID at sentencing (n = 53).

- Georgia Senate Bill 174, available at https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/legislation/document/20172018/168761.