Justice Reinvestment Initiative in New Hampshire

To achieve better health and safety outcomes, New Hampshire leaders have long worked to understand and address the challenges of how people move through state and local criminal justice and health systems. In recent years, the state has formed task forces, dedicated resources, and supported programs that are focused on addressing mental illnesses, substance use disorders (SUDs), and the co-occurrence of both. However, county and state officials continue to report a high prevalence of people with behavioral health needs moving through county departments of corrections (jails) and state prisons, as incarceration settings are often the only option for holding and treating people with behavioral health challenges.

Stakeholders and state leaders have expressed concern that community-based resources for people with behavioral health challenges are limited across the state. County officials report significant gaps in how the state is currently responding to and serving people with behavioral health needs. These gaps are especially apparent for people with co-occurring disorders and the subset of that population composed of people who are high utilizers of multiple systems, such as jails, prisons, law enforcement, community supervision, emergency rooms, crisis services, and housing and homelessness services. Without more effective and available community-based services to respond to people with substance use disorders, mental illnesses, or both, New Hampshire has increasingly relied on incarceration in jails or prison to address behavioral health challenges, which increases fiscal pressure on counties. To reduce the cycle of incarceration for people with mental health and substance use needs, the state needs solutions that appropriately respond to people in the justice system who are high utilizers of the jail and behavioral health systems.

To this end, Governor Chris Sununu, Commissioner Lori Shibinette of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Commissioner Helen Hanks of the Department of Corrections (NHDOC), Chief Justice Tina Nadeau of the state’s superior court, the New Hampshire Association of County Corrections Affiliate (which is made up of the 10 jail superintendents in the state), Senator Tom Sherman, and Representative Bob Lynn (former chief justice of the supreme court) requested support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) to launch a Justice Reinvestment Initiative in March 2022. As public-private partners in the federal Justice Reinvestment Initiative, BJA and Pew approved New Hampshire state leaders’ request and asked The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center to provide intensive technical assistance.

Under the direction of the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Mental Illness and the Corrections System (Advisory Commission), CSG Justice Center staff are working with DHHS and county jails to facilitate a cross-system data match that will identify the population of people with behavioral health needs who frequently move through local criminal justice systems. CSG Justice Center staff are also using a Medicaid data match to glean utilization trends within the public health system. Additionally, CSG Justice Center staff are conducting focus groups with key stakeholders to better understand the challenges they encounter in identifying and addressing the behavioral health needs of people who are high utilizers. Based on the findings from these quantitative and qualitative analyses, the Advisory Commission, DHHS, and jail superintendents will consider and develop policy options that are designed to improve services for people with behavioral health needs within the criminal justice system, reduce recidivism, and increase public safety and public health outcomes throughout the state.

Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health Trends in New Hampshire

New Hampshire jail incarceration rates are increasing, likely driven by behavioral health pressures.

- In Cheshire County, 84 percent of people in jail who received a mental health assessment in 2019 met the criteria for alcohol and/or drug use disorder or dependence, and 64 percent had co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders.1

- Similarly, the Coos County Department of Corrections estimated that in 2019, about a quarter of people incarcerated in its jail had an opioid use problem.2 In Merrimack County, over two-thirds of people in jail in 2019 reported using drugs on a regular basis.3 And an analysis conducted by the Sullivan County Department of Corrections found a 76 percent overlap between people in the county jail and people served by the community mental health center.4

- About one-third of all jail bookings in Belknap County in 2019 were for protective custody holds—civil commitments for behavioral health crises.5

- The Rockingham County Department of Corrections reported that over half of people booked in the county jail in 2018 were identified as “repeat offenders,” possibly due to behavioral health conditions.6

- Data show that revocations to state prison from community supervision and parole are also driven by behavioral health challenges. In 2019, 50 percent of admissions to state prison were for parole violations.7 In 2017, sub-stance use and failure to comply with treatment were the most common parole violations committed,8 and in 2020, substance use was listed as a reason for revocation in over half (56 percent) of parole revocation hearings that resulted in revocation.9

Despite tremendous behavioral health needs in New Hampshire, mental illness and substance use disorder treatment and service providers have a limited ability to meet these needs generally, let alone for people in the criminal justice system.

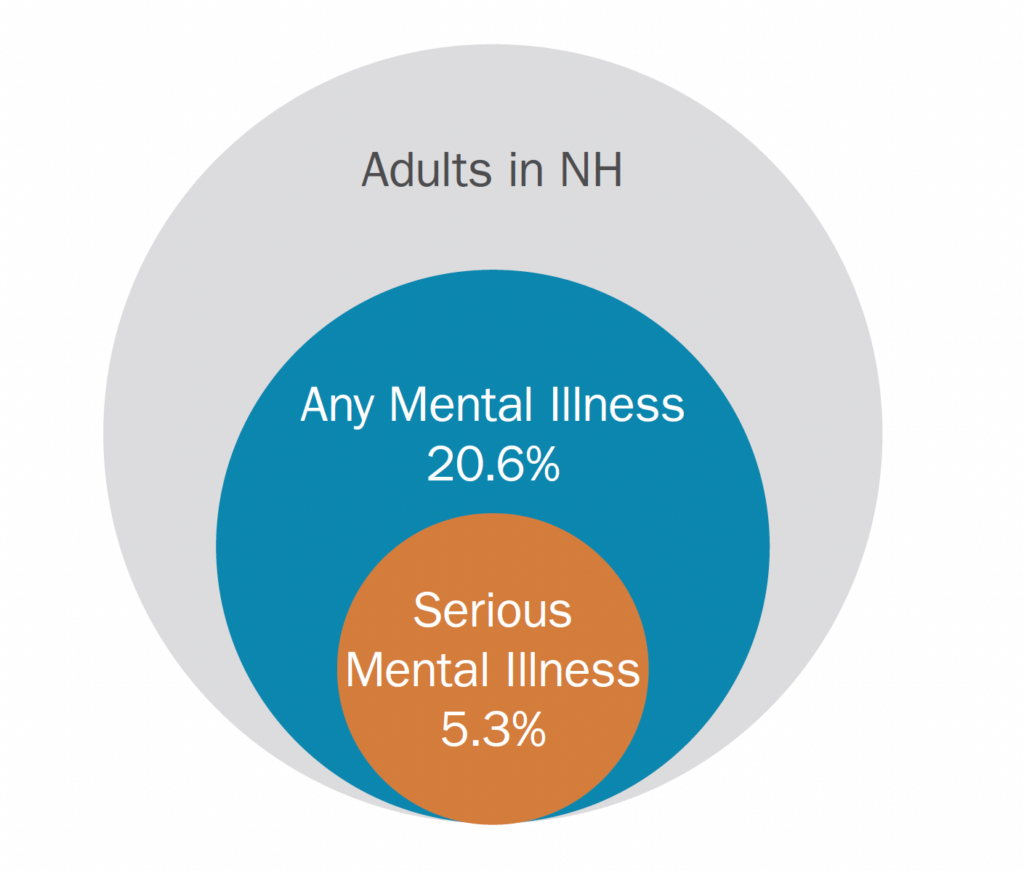

- In 2017 and 2018, an estimated 20.6 percent of adults in New Hampshire had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional condition (i.e., any mental illness, or AMI) and 5.3 percent had a serious mental illness (SMI) each year. New Hampshire’s rates were slightly higher than the national average of 19 percent and 4.6 percent, respectively, in 2017 and 2018.10 (See Figure 1.)

- Suicide increased 62 percent between 2009 and 2018, from 12.2 to 19.8 deaths per 100,000 residents in New Hampshire.11

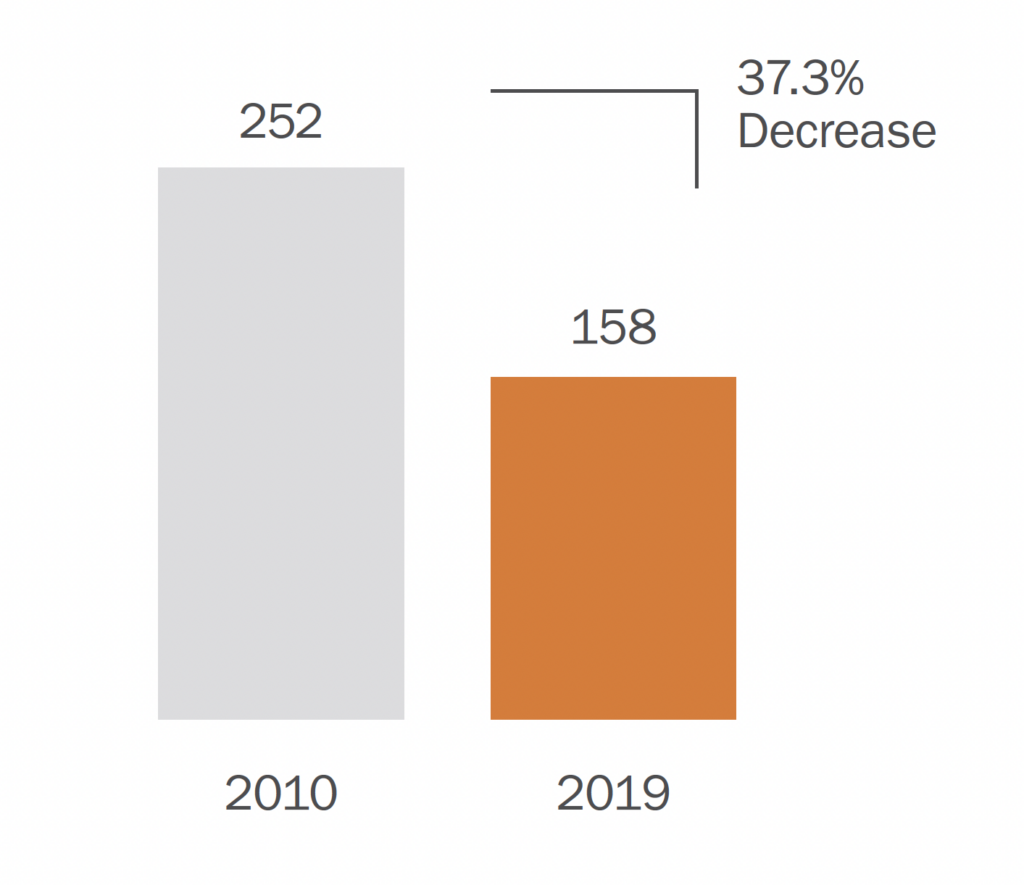

- Between 2010 and 2019, the capacity of the New Hampshire Hospital, the state-operated psychiatric facility, decreased from 252 beds to 158.12 (See Figure 2.)

- Half of New Hampshire counties have been designated as mental health professional shortage areas.13

- From 2015 to 2017, 1.4 percent of people aged 12 or older in New Hampshire had opioid use disorder in the previous year, nearly twice the national average (0.8 percent).14

- New Hampshire had the 11th-highest rate of substance use disorder in the nation in 2017 and 2018, with an estimated 9 percent of adults having a substance use disorder in the past year.15

- In 2017 and 2018, an estimated 9 percent of adults in New Hampshire needed substance use treatment but did not receive it, the seventh-highest rate in the nation.16

- In 2019, the state recognized that behavioral health supports are lacking for people in the criminal justice system, and unaddressed challenges can lead to homelessness, increased emergency department visits, rear-rests, and recidivism. Executive Order 2019-02 established the Governor’s Commission on Mental Illness and the Corrections System to address barriers to accessing mental health services, substance use disorder treatment, and other necessary supports for people involved in the correction systems.

Health care, including that related to people with behavioral health challenges, remains a significant driver of costs for the state and county criminal justice systems.

- In 2019, the NHDOC spent nearly $15 million on medical expenses.17 The exact amount spent on behavioral health is unknown, but in 2018, behavioral health services accounted for one-third of the department’s medical appointments,18 and in 2019, pharmaceutical costs were driven by treatment for hepatitis C and purchase of medications to treat opioid dependence.

- In 2019, the NHDOC spent $6 million on community-based health care for people in prison, with an additional $1.6 million for inpatient stays covered by Medicaid.19

- In 2018, the NHDOC submitted nearly 800 Medicaid applications for people being released from prison to ensure continued access to health care services after release.20 Given current Medicaid suspension policies while people are incarcerated, the NHDOC incurs the cost of providing general and behavioral health care to the incarcerated population.

- The state increased funding for mental health services (excluding New Hampshire Hospitals and the Medicaid program) from $7.3 million to nearly $50 million between 2013 and 2019.21

Figure 1: Percentage of Adults in New Hampshire with a Diagnosable Mental Illness or Serious Mental Illness, 2017–2018

Figure 2: Decrease in New Hampshire Hospital Capacity, 2010–2019

The Justice Reinvestment Initiative Approach

Step 1: Analyze data and develop policy options

Under the direction of the Advisory Commission, CSG Justice Center staff are working with DHHS and county jails to facilitate a cross-system data match to identify the overlapping population of people who have behavioral health challenges, who move through local criminal justice systems, and who can be identified as high utilizers of health and criminal justice systems. CSG Justice Center staff will analyze (1) Medicaid claims activity data for people prior to and after incarceration in the county jail to understand how people with identified behavioral health needs access resources and supports across the state and (2) county jail data related to demographics, bookings and releases, screenings and assessments, medications, and programming and treatment to understand the criminal justice and behavioral health characteristics of locally incarcerated populations. CSG Justice Center staff will also conduct a qualitative assessment of jail behavioral health services, programs, and treatment to better understand challenges and identify recommendations for improvement. This assessment will include focus groups with superintendents, jail staff, community mental health center staff, substance use disorder treatment and recovery support service providers, and housing and homeless-ness service providers. To incorporate perspectives from across the state, CSG Justice Center staff are collecting input from criminal justice system stakeholders including county judges, county attorneys, law enforcement, local police chiefs, public defenders, local officials, and behavioral health organizations.

With the assistance of CSG Justice Center staff, the Advisory Commission, DHHS, and county jail leadership will review the analyses and develop policy and practice recommendations focused on increasing public safety by expanding available services and improving outcomes for people with behavioral health needs within the criminal justice system. The Advisory Commission will consider recommendations in early 2023.

Step 2: Adopt new policies and put reinvestment strategies into place

If the recommendations are formalized via legislation, court rules, agency policy, etc., CSG Justice Center staff will work with New Hampshire policymakers and administrators for a period of 12 to 24 months to translate the changes into practice. This assistance will help ensure that related programs and system enhancements achieve projected outcomes and are implemented using the latest research-based, data-driven strategies. CSG Justice Center staff will develop implementation plans with state and local officials, provide policymakers with frequent progress reports, and deliver testimony to relevant legislative committees.

Step 3: Measure performance

Finally, the CSG Justice Center will help New Hampshire officials improve statewide data collection and sharing to measure and monitor performance as well as, ultimately, increase the state’s capacity for making data-driven deci-sions to support policymaking for people who frequently cycle between the jails and local behavioral health sys-tems. This could include identifying key data points to record and officials best positioned to collect data, shar-ing data across the public safety and health systems, as well as exploring best practices to track, monitor, and ana-lyze data on a regular basis for high utilizers of multiple systems. Improving data collection and sharing will allow state and local leaders to assess the impact of enacted policies on people with behavioral health needs in the justice system.

Endnotes

- County of Cheshire, Report of the County Commissioners County Treasurer and Other Officers of Cheshire County New Hampshire for the Year Ending December 31, 2019 (Keene, NH: County of Cheshire, 2020). Of the 1,610 people booked in calendar year 2019, 280 received a mental health evaluation. Information on mental health in jails was not available for all counties.

- County of Coös, Annual Report of Coös County for the Year Ending December 31, 2019 (Lancaster, NH: County of Coös, 2020). Information on substance use in jails was not available for all counties.

- Merrimack County, ANNUAL REPORT For the year ending December 31, 2019 (Concord, NH: County of Merrimack, 2020). “69% of inmates self-reported regular drug use.” Self-reported drug use statistics were not available for all counties.

- Meeting between The Council of State Governments Justice Center and Sullivan County, Department of Corrections on November 18, 2020.

- County of Belknap, 2019 Annual Report (Laconia, NH: County of Belknap, 2020). Of 1,687 total bookings, 590 (35% percent were protective custody holds. Information on booking types was not available for all counties.

- Rockingham County, Annual Report Fiscal Period Ending June 30, 2019 (Brentwood, NH: Rockingham County, 2019). The Department of Corrections numbers in this report were as of March 2018. Of 3,534 reported intakes, 1,957 (55 percent) were listed as “repeat offenders.” No information on how repeat offenders were identified was included in the report. Information on prior activity was not available for all counties.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, SFY2019 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2020).

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, SFY2018 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2019). Information on parole revocation reasons was based on Parole Board activity during calendar year 2017.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, NH DOC Monthly Parole Hearings Summary Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections,2020). Numbers are for January 1, 2020, to December 1, 2020. There were parole revocation hearings during this period, of which 538 resulted in revocation. Revocations can be due to multiple reasons.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017–2018 NSDUH State Estimates Of Substance Use And Mental Disorders (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse andMental Health Services Administration, 2019). Percentages are annual aver-ages for 2017 and 2018; rates for individual years were not available. Adults are people 18 years of age and older.

- “Suicide in New Hampshire,” America’s Health Rankings United Health Foundation, accessed February 11, 2021, https://www.americashealthrank-ings.org/explore/annual/measure/Suicide/state/NH.

- New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Bureau of Mental Health Services, Mental Health Block Grant NH Plan: Federal Fiscal Years 2020–2021 System Assessment (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department ofHealth and Human Services, Bureau of Mental Health Services 2019).

- “HPSA Find,” United States Health Resources and Services Administration, accessed December 17, 2020, https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/ hpsa-find. The designated counties are Belknap, Carroll, Coös, Grafton, and Merrimack. All are considered rural counties.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Behavioral Health Barometer New Hampshire, Volume 5 (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Percentages are annual averages for 2015–2017; rates for individual years were not provided. Rates for people 18 years of age and older were not listed in the report.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Behavioral Health Barometer: New Hampshire, Volume 6: Indicators as measured through the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse andMental Health Services Administration, 2020), www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/ default/files/reports/rpt32846/NewHampshire-BH-Barometer_Volume6.pdf.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017–2018 NSDUH State Estimates of Substance Use and Mental Disorders (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse andMental Health Services Administration, 2019). Percentages are annual aver-ages for 2017 and 2018; rates for individual years were not available. Adults are people 18 years of age and older.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, FY2019 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2020). The New Hampshire fiscal year is July 1 through June 30.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, SFY2018 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2020). The New Hampshire fiscal year is July 1 through June 30. There were 75,272 appointments reported for FY2018: 24,302 for behavioral health services, 42,088 for medical services, and 8,882 for dental services.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2019 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2020). The New Hampshire fiscal year is July 1 through June 30. The department reported $5,975,092 in “General Fund Expense Medical Payments to Providers 8234 Class 101” and $1,587,388 in “Total Inpatient Stays Paid by Medicaid (90 Day retroactive coverage)” for FY2019. There were 114 episodes of Medicaid-paid care, such as hospital stays and outpatient procedures.

- New Hampshire Department of Corrections, SFY2018 Annual Report (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 2019). The New Hampshire fiscal year is July 1 through June 30. Medicaid application numbers were not included in the 2019 annual report.

- New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, New Hampshire 10-Year Mental Health Plan (Concord, NH: New HampshireDepartment of Health and Human Services, 2019).

This project was suppor ted by Grant No. 2019-ZB-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit organization that serves policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels from all branches of government. The CSG Justice Center’s work in justice reinvestment is done in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance. These efforts have provided data-driven analyses and policy options to policymakers in 26 states. For additional information about Justice Reinvestment, please visit csgjusticecenter.org/jr/.

Research and analysis described in this report has been funded in part by The Pew Charitable Trusts public safety performance project. Since 2005, The Pew Charitable Trusts and its partners have conducted research, provided technical assistance and legislative support to governments, and made strategic grants to advance fiscally sound, data-driven criminal and juvenile justice policies and practices that protect public safety and reduce correctional populations and costs. To learn more about the project, please visit pewtrusts.org/publicsafety.

Project Contact: Madeleine Dardeau, Project Manager, mdardeau@csg.org