Nebraska’s Criminal Justice System: Urgent Challenges & Proposed Policy Solutions

The Challenge

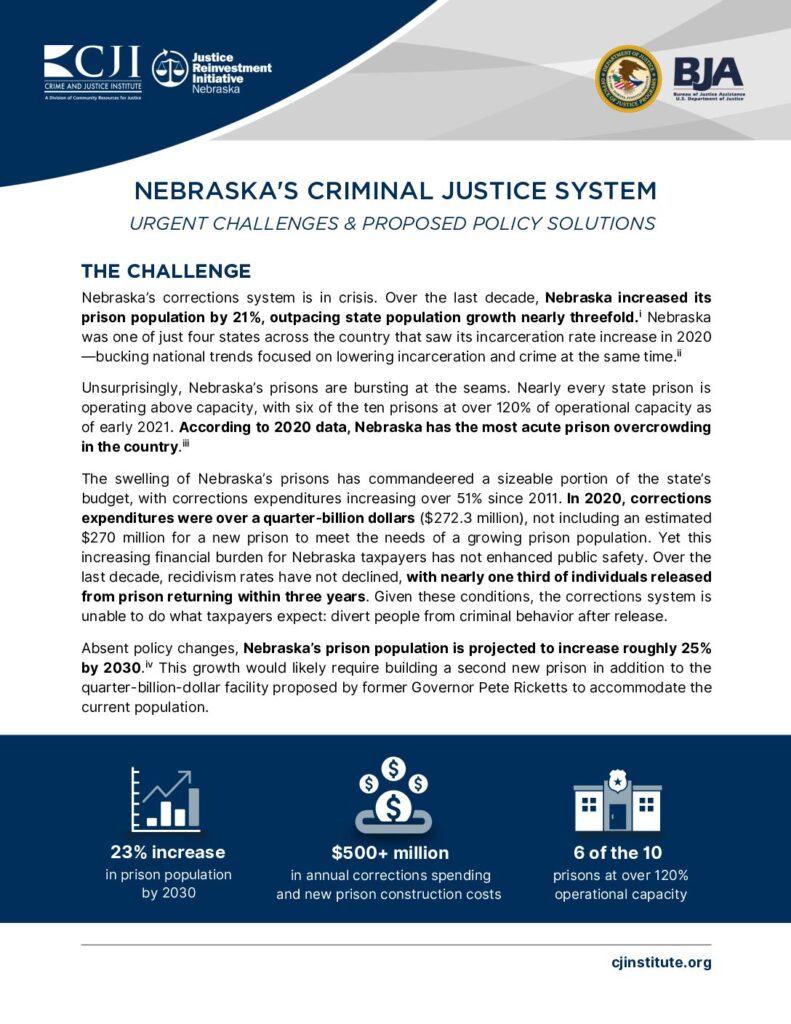

Nebraska’s corrections system is in crisis. Over the last decade, Nebraska increased its prison population by 21%, outpacing state population growth nearly threefold.ⁱ Nebraska was one of just four states across the country that saw its incarceration rate increase in 2020 —bucking national trends focused on lowering incarceration and crime at the same time.ⁱⁱ

Unsurprisingly, Nebraska’s prisons are bursting at the seams. Nearly every state prison is operating above capacity, with six of the ten prisons at over 120% of operational capacity as of early 2021. According to 2020 data, Nebraska has the most acute prison overcrowding in the country.ⁱⁱⁱ

The swelling of Nebraska’s prisons has commandeered a sizeable portion of the state’s budget, with corrections expenditures increasing over 51% since 2011. In 2020, corrections expenditures were over a quarter-billion dollars ($272.3 million), not including an estimated $270 million for a new prison to meet the needs of a growing prison population. Yet this increasing financial burden for Nebraska taxpayers has not enhanced public safety. Over the last decade, recidivism rates have not declined, with nearly one third of individuals released from prison returning within three years. Given these conditions, the corrections system is unable to do what taxpayers expect: divert people from criminal behavior after release.

Absent policy changes, Nebraska’s prison population is projected to increase roughly 25% by 2030.ⁱᵛ This growth would likely require building a second new prison in addition to the quarter-billion-dollar facility proposed by former Governor Pete Ricketts to accommodate the current population.

The Solution

In spring 2022, the Nebraska legislature debated a bill containing data-driven justice reform policies to reduce the state’s projected prison growth while promoting public safety and reducing recidivism. The bill, LB 920, was the product of a yearlong effort by a bipartisan group of stakeholders from across the state, the Nebraska Criminal Justice Reinvestment Working Group. Based on years of criminological research, LB 920’s policies were crafted to maximize taxpayer resources by reserving prison beds for serious offenses, expanding alternatives to incarceration, and improving community-based behavioral health services to interrupt misconduct and prevent crime. Had LB 920 passed, it would have decreased projected prison population growth by over 1,000 people by 2030, saving the state more than $55 million in additional costs.

Sentence enhancements cost taxpayers significantly yet provide minimal public safety benefit. As predicted by the research, funneling more taxpayer funds to cover longer stays has not improved justice system outcomes, as recidivism rates have remained high. Despite this, Nebraska continues to use longer sentences for less serious, non-violent criminal behaviors.

Policy Priorities

1. Preserve Prison Beds for the Most Serious Misconduct

Research shows that imprisonment harms individuals’ health, economic stability, and positive relationships, all of which may contribute to increased criminal involvement following release.ᵛ Moreover, there is no conclusive evidence suggesting that longer prison stays are more effective at reducing recidivism or protecting public safety than shorter stays, and, in certain contexts, longer stays have been shown to increase the likelihood of recidivism.ᵛⁱ Despite these findings, the average length of stay on a prison sentence in Nebraska grew by 38% from 2011 to 2020, driven in part by longer sentences resulting from consecutive sentences, mandatory minimums, and habitual criminal enhancements.

Sentence enhancements cost taxpayers significantly yet provide minimal public safety benefit. As predicted by the research, funneling more taxpayer funds to cover longer stays has not improved justice system outcomes, as recidivism rates have remained high. Despite this, Nebraska continues to use longer sentences for less serious, non-violent criminal behaviors.

Policy Recommendations

- Reserve mandatory minimum sentences for violent and serious offenses.*

- Ensure habitual criminal enhancement statute is used only for violent or sex offenses.*

- Modify credit accrual for those with mandatory minimum sentences to incentivize behavior change.*

- Reduce the use of discretionary consecutive sentences.*

Potential Impact

- Long sentences are a primary driver of Nebraska’s prison population. Limiting sentencing enhancements could significantly reduce the length of time people spend in prison and therefore the overall prison population.

- Nebraska can save more than 300 prison beds by 2030 by implementing all four policy recommendations described above.vii

*Starred policies did not receive consensus support from the working group.

2. Tailor Penalties with Severity of Conduct

Criminological research has consistently found that incarceration is not more effective at reducing recidivism than non-custodial sanctions such as probation.ᵛⁱⁱⁱ In fact, incarceration may lead to higher rates of recidivism for certain types of lower-level behavior, like drug offenses and technical violations, and is significantly more expensive to taxpayers than alternatives to incarceration.ⁱˣ The total cost to house a person in state prison is over $40,000 per year.ˣ Given that, it is critical that Nebraska policymakers ensure that the length of a prison sentence corresponds to the severity of the conduct.

Drug Possession

Drug possession was the leading offense for admission to Nebraska prisons in 2020. Unlike many other states, Nebraska categorizes possession of controlled substances other than marijuana as a felony, regardless of the amount possessed. This means that people who are addicted to drugs and in possession for personal use—not sale—are punished with felony sentences. Research suggests that deterrence (i.e., threatening punishment) does not work for many drug users because of the seriousness of their behavioral health disorders.ˣⁱ A more effective response to drug possession may be alternatives to incarceration, such as treatment.

Property Crime

Unlike many states, Nebraska considers a third or subsequent shoplifting offense to be a felony, even when the value of the item is below the typical threshold for felony theft, $1,500. This means that people can be convicted of a felony and go to prison for stealing something under five dollars, if it is a third theft offense. In 2020, property offenses represented more than 10% of admissions to the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services (NDCS). Of those, shoplifting was among the most frequent.

Burglary

Burglary was the top property offense for the admissions in 2020, and the sixth most common offense overall, constituting 5% of all admissions. While many states differentiate types of burglary based on seriousness (e.g., home invasion versus breaking into an abandoned commercial building), Nebraska’s burglary statute covers a broad range of conduct and treats all types of burglaries the same despite differing levels of severity. Additionally, Nebraska law authorizes a wide sentencing range of incarceration anywhere up to 20 years for any burglary, which is applied inconsistently across the state.

policy Recommendations

- Create misdemeanor level for possession of residue of a controlled substance.*

- Establish a look back period for habitual theft under $500.

- Create a tiered penalty structure for different burglary conduct.

Potential Impact

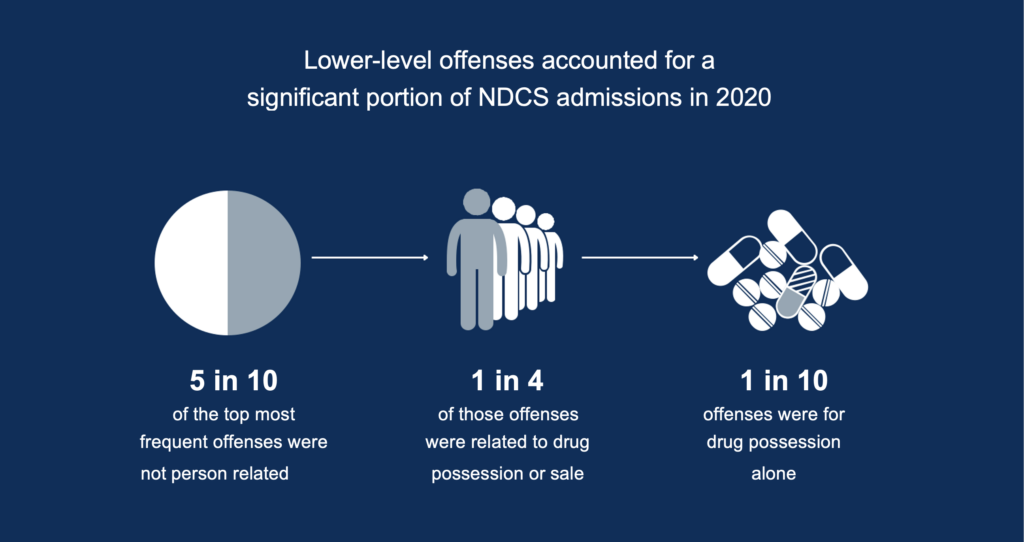

- Five of the top ten most frequent offenses at admission to NDCS in 2020 were offenses that did not cause or risk bodily harm to another person. Possession of a controlled substance other than marijuana together with possession with intent to deliver accounted for almost a quarter of all admissions, while possession alone comprised 13%.

- Nebraska can save more than 100 prison beds by 2030 by implementing all three policy recommendations described above.

*Starred policies did not receive consensus support from the working group.

3. Streamline Release for People Prepared to Reenter Society

As sentence lengths increased on the front end of the criminal justice system, releases from prison—through sentence expiration, release to post-release supervision, and parole— plateaued on the back end. In 2018, 78% of eligible people were granted parole; two years later, that percentage dropped to just 58%. At the same time, people ultimately released on parole spent longer in prison ahead of release: 60% more time than in 2011. In sum, fewer people were granted parole, and when released, they had been in prison longer.

A variety of factors have contributed to this decline in parole rates and increase in time served, including: longer sentences at the front end (see priority 1); a parole process with multiple meetings and reviews; and the number of criteria the Board of Parole must evaluate, many of which are subjective and unrelated to public safety. As described above, imprisonment harms individuals’ health, economic stability, and positive relationships, all of which may contribute to increased criminal involvement following release.ˣⁱⁱ

policy Recommendations

- Eliminate “flat sentences” that prevent parole release even when all statutory criteria for parole eligibility are met. “Flat sentences” occur when someone is sentenced to minimum and maximum terms that are the same.

- Streamline the parole process for eligible, low-risk people serving sentences for nonviolent offenses.

- Align parole criteria with current criminological research on recidivism.

- Establish a geriatric parole option where appropriate for people over the age of 70.*

potential impact

Nebraska can save more than 100 prison beds by 2030 by implementing all three policy recommendations described above.

*Starred policies did not receive consensus support from the working group.

4. Expand Alternatives to Incarceration

Research has found that incarceration is no more effective at reducing recidivism than alternatives to incarceration like probation.ˣⁱⁱⁱ Alternatives to incarceration have the potential to lower costs by limiting interaction with the court, reducing both time and costs associated with the court process, and enable investment in local treatment programs that prevent people from cycling back into the justice system.

Numerous judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys interviewed during the working group process spoke of the need for more investment in alternatives to incarceration and diversion opportunities for appropriate lower-level offenses. Availability of diversion programs varies widely across the state because they are administered county by county and county attorneys are solely responsible for their establishment and oversight. As a further barrier, while the Nebraska Supreme Court outlines eligibility standards for each type of problem-solving court, in practice candidates must be approved by the prosecutor in many counties.

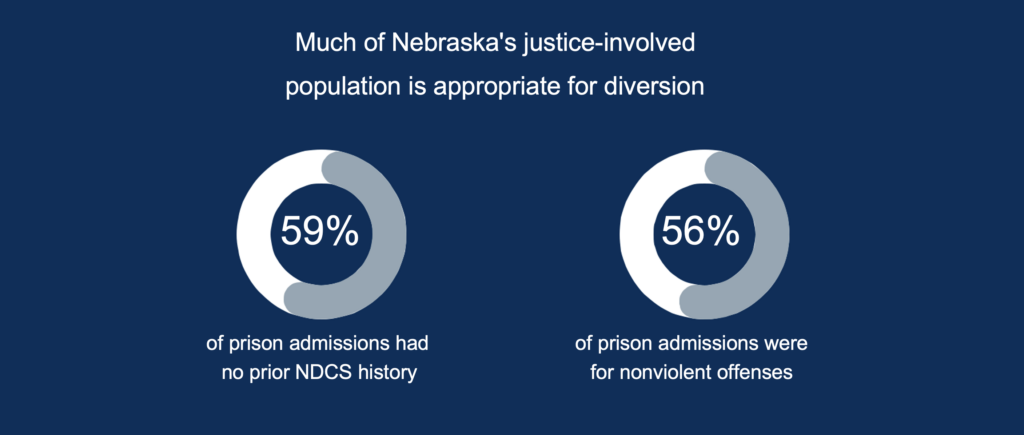

The data demonstrate that a substantial portion of the justice-involved population may be appropriate candidates for diversion: 59% of admissions to custody had no prior NDCS history, and 56% of individuals admitted to prison in 2020 were sentenced for nonviolent offenses.

policy Recommendations

- Create a standard structure for diversion programs statewide, with ample flexibility to address local needs and challenges, and reinvest state funding in counties to administer programs.

- Establish additional problem-solving courts where appropriate and evaluate outcomes to inform future efforts.

- Establish standardized eligibility criteria for problem-solving courts and use a team model for selecting participants.

Potential Impact

- In 2020, more than half of initial admissions were for Felony IIIA or Felony IV offenses, the two least serious felony classes in the state. Of those individuals, more than half had no prior involvement with NDCS. Moreover, more than a third of all property offenses and more than half of all drug offenses admitted to NDCS in 2020 were for Felony IV, the least serious felony class.

- Increasing the use of alternatives to incarceration—in line with best practice—could shift some lower-level felonies to diversion programs or probation, resulting in a decrease in admissions to prison.

- Though there is insufficient information to generate specific numeric projections, the more diversion is used, the greater the reduction in prison population and related system costs, along with increased access to effective interventions to treat behavior driving criminal offenses.

5. Enhance Reentry Supports for Justice-Involved People

People who are released from prison and return to their communities face numerous barriers including employment, housing, behavioral health treatment, medical care, transportation, and childcare. This process is made more difficult when appropriate and necessary resources are unavailable or difficult to access. As one example, recently released individuals interviewed during the working group process explained that accessing healthcare during the reentry process is a common barrier, and behavioral health experts shared that acquiring Medicaid coverage can be complicated and therefore delay prompt care. Additionally, while people exiting prison are released with a parole reentry plan, it focuses mainly on finding appropriate housing and does not address other related challenges.

Unsurprisingly, Nebraska’s recidivism rate has increased over time, with 30% of those released in 2018 returning to NDCS custody, up four percentage points from 2008. Improving basic services for people exiting prisons is critical to reducing recidivism.

Policy Recommendations

- Require tracking of the use of the NDCS and Department of Health and Human Services program that enrolls individuals released from prison in Medicaid.

- Ensure responsivity factors are considered in the parole planning process to help address reentry barriers.

Potential impact

Improving the reentry process and providing more support for those returning to their communities—in line with current criminological research—could reduce recidivism and parole revocations that contribute to prison admissions. However, information is insufficient to generate specific numeric projections.

6. Invest in Community-based Behavioral Health Services

Like many states, Nebraska has major gaps in its community-based behavioral health resources. These gaps are even greater for people seeking care outside of large cities. Although Nebraska expanded efforts to implement telehealth services during the pandemic, there are critical shortages in services and a patchwork of programming with disparate outcomes across the state.

With few accessible treatment options to address underlying issues that drive criminal behavior, Nebraska’s prisons have become a repository for people with complex behavioral health needs. People with mental health and substance use disorders fare better in treatment than in incarceration.ˣⁱᵛ Money saved from diverting people from prison should be directed to community-based services.

Policy Recommendations

- Increase access to telehealth services for court-involved individuals by establishing a pilot program to use courthouses as connection access points for virtual behavioral health service appointments.

- Increase student loan assistance for mental health providers in shortage areas.

Potential impact

- People with behavioral health needs are disproportionately represented in the justice system.ˣᵛ The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that people with serious mental illness are booked into jails about two million times per year, and about 40% of incarcerated individuals have a history of mental illness.ˣᵛⁱ

- By prioritizing programming that targets an individual’s criminogenic needs and improving access to treatment services, Nebraska can better address underlying issues driving criminal behavior.ˣᵛⁱⁱ Though there is insufficient information to generate specific numeric projections, these policies will increase diversion opportunities, reduce recidivism, and improve public safety—thereby decreasing the need for additional prison beds.

7. Support Community Supervision Best Practices

The agencies responsible for community supervision in Nebraska have made great progress over the last decade in implementing evidence-based practices in line with the goals of the previous JRI effort. As a result of a shift to using community supervision more effectively, the number of people supervised on probation has grown 70% in a decade, and many of these people have complex needs and challenges. Supervising agencies are also facing staffing shortages. As a result of all these factors, community supervision officers have reported feeling overloaded and stressed.

On the parole side, admissions to prisons for parole revocations have increased over the past decade. One in six admissions to NDCS comes either from parole or post-release supervision failure. Moreover, those revoked from parole and returned to NDCS custody in 2020 served significantly longer in prison than in 2011 (78% longer). In other words, more people are failing on parole and post-release supervision, and they are staying longer in prison when they are reincarcerated.

Roundtable discussions with people directly impacted by the justice system and providers of behavioral health services suggest failures on community supervision are often driven by limited treatment options for substance use disorder or mental health diagnoses that may contribute to criminal behavior, especially in more rural parts of the state.

Policy Recommendations

- Hire additional assistant probation officers to support high-risk caseloads.

- Create statewide standards for early discharge on probation.

- Provide funding for tangible incentives to promote prosocial behavior, condition completion and supervision success, and to align current practice with research.

- Provide greater residential housing support for people on community supervision, especially those on parole who commit technical violations.

- Inform people who have successfully completed probation that they may have their conviction(s) set aside to remove barriers associated with their criminal conviction(s).

Potential Impact

Though information is insufficient to generate specific numeric projections, Nebraska can reduce prison admissions for probation and parole violations by continuing to improve supervision practices and focusing resources on the highest-risk populations.

Additional Recommendations

The working group recommended several additional policies that cut across priority areas:

- Prioritize restitution to crime victims above other legal financial obligations imposed by the court.

- Reconvene the working group to monitor the implementation and fidelity of justice system reforms.

- Enhance stakeholder education on young adult brain development to inform decisions in the justice system.

Though there is insufficient information to generate specific numeric projections relative to these recommendations, many policies recommended by the working group enable the state to make accurate predictions on prison population trends in the future.

Acknowledgements

This brief was prepared by Molly Robustelli, Lisa Margulies, and Amanda Coscia with assistance from staff members Carrie Chapman, Colby Dawley, Leonard Engel, Celeste Gander, Maura McNamara, Razmeet Samra, and Christian Schiavone.

This project was supported by Grant No. 2019-ZB-BX-K003 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Endnotes

i Unless otherwise stated, all Nebraska figures are CJI’s analysis of data from Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, Nebraska Division of Parole Supervision, and Nebraska’s Administrative Office of the Courts & Probation provided during the working group process. Population counts from the U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 and 2020.

ii Weihua Li, David Eads, and Jamiles Lartey. “There are fewer people behind bars now than 10 years ago, will it last?” The Marshall Project, September 20, 2021, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/09/20/there-are-fewer-people-behind-bars-now-than-10-years-ago-will-it-last.

iii E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2020—Statistical Tables (Washington, D.C.: Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. 2021), 34, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p20st.pdf.

iv The JFA Institute, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, Ten-Year Population Projections, FY 2020-2030 (Denver, CO: 2018), http://news.legislature.ne.gov/jud/files/2022/03/JFA-Projections-2020.pdf.

v Katherine Beckett and Allison Goldberg, “The Effects of Imprisonment in a Time of Mass Incarceration,” Crime and Justice 51 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1086/721018.

vi G. Matthew Snodgrass, et al., “Does the Time Cause the Crime? An Examination of the Relationship Between Time Served and Reoffending in the Netherlands,” Criminology 49 (2011): 1149-1194; Thomas A. Loughran, et al., “Estimating a Dose-Response Relationship Between Length of Stay and Future Recidivism in Serious Juvenile Offenders,” Criminology 47 (2009): 699-740; The Pew Charitable Trusts, Time Served: The High Cost, Low Return of Longer Prison Terms (Washington, D.C.: 2012), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports /2012/06/06/time-served-the-high-cost-low-return-of-longer-prison-terms.

vii Prison population projections are estimates calculated by CJI and assume policies are implemented with fidelity.

viii Beckett and Goldberg, “The Effects of Imprisonment in a Time of Mass Incarceration.”

ix William D. Bales and Alex R. Piquero, “Assessing the impact of imprisonment on recidivism,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 8, no. 1 (2012): 71-101; Cassia Spohn and David Holleran, “The effect of imprisonment on recidivism rates of felony offenders: A focus on drug offenders,” Criminology 40, no. 2 (2002): 329-358; Elizabeth K. Drake and Steve Aos, Confinement for technical violations of community supervision: Is there an effect on felony recidivism, (Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2012).

x Henry J. Cordes, “Paying the Price: Nebraska gun law helped spark nation-leading prison growth,” Omaha World-Herald, January 9, 2022, https://omaha.com/news/state-and-regional/crime-and-courts/paying-the-price-nebraska-gun-law-helped-spark-nation-leading-prison-growth/article.

xi Linda C. Fentiman, “Rethinking Addiction: Drugs, Deterrence, and the Neuroscience Revolution,” U. Pa. JL & Soc. Change 14 (2011): 233, http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jlasc/vol14/iss2/2.

xii Beckett and Goldberg, “The Effects of Imprisonment in a Time of Mass Incarceration.”

xiii Id.

xiv Chandler, Redonna K., Bennett W. Fletcher, and Nora D. Volkow, “Treating Drug Abuse and Addiction in the Criminal Justice System.” JAMA 301, no. 2 (2009): 183. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.976.

ˣᵛ Henry J. Steadman, et al., “Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates.” Psychiatric Services 60 no. 6 (2009): 761-765; Jeremy Travis, Bruce Western, and F. Stevens Redburn, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences (Washington, D.C.:National Research Council of the National Academies, 2014).

xvi National Alliance on Mental Illness, Mental illness and the criminal justice system, https://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Infographics/NAMI_CriminalJusticeSystem-v5.pdf.

xvii The Pew Charitable Trusts, More Imprisonment Does Not Reduce State Drug Problems, (Washington, D.C.: 2018), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2018/03/more-imprisonment-does-not-reduce-state-drug-problems.