National Context

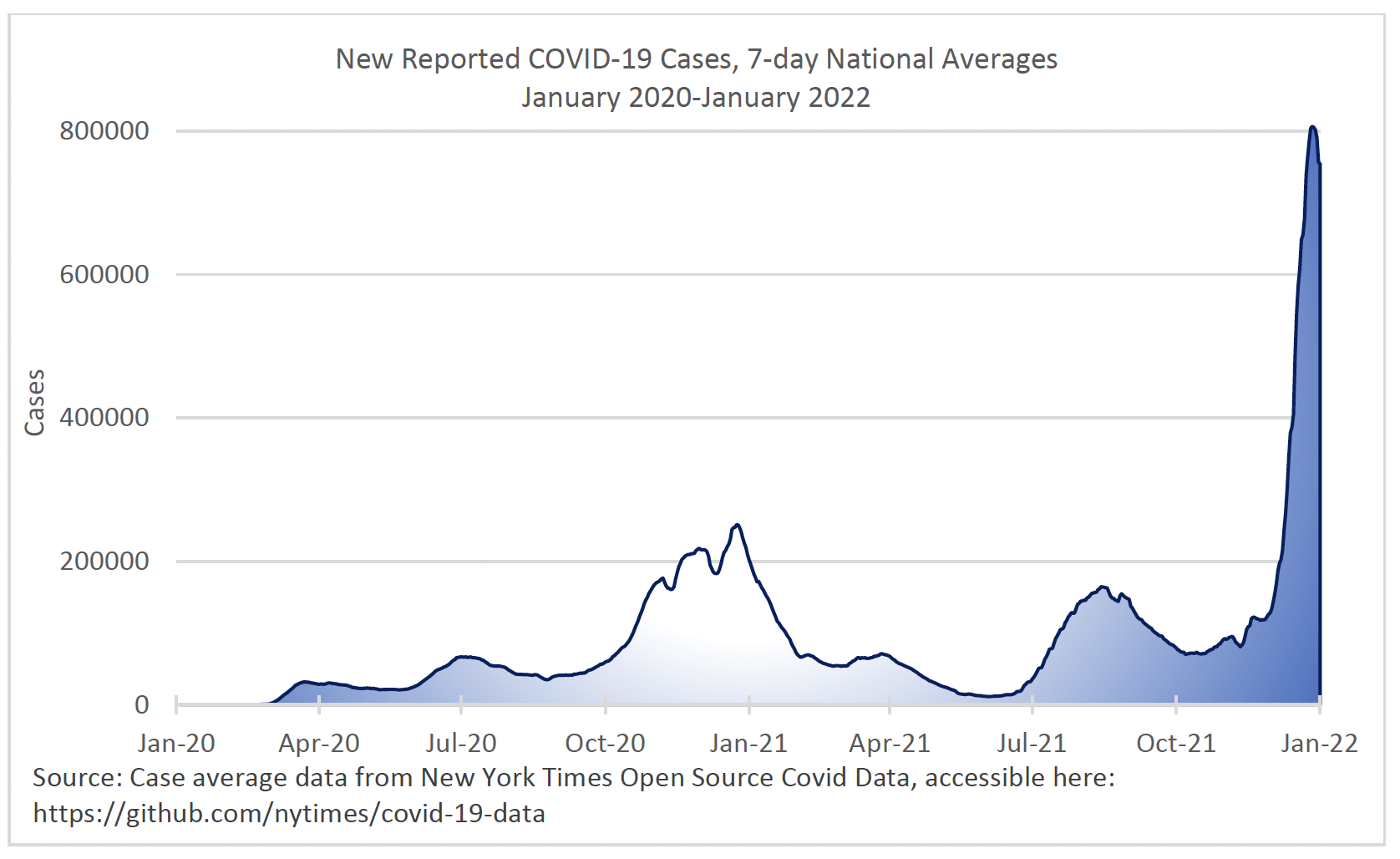

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of COVID-19 in the U.S. in late January 2020, from samples taken in Washington State.2 This represented the early stages of what is now a global pandemic with far-reaching effects on every sector of American life. Since that initial case, throughout the country there have been spikes in reported cases from late November 2020 to the end of January 2021, in the late summer of 2021, and at the end of 2021 into early 2022 (see Figure 1). Hospitalizations, deaths, and testing rates have largely followed the same overall pattern as cases, with hospitalization and death rates peaking slightly later than testing and case rates.3

Figure 1. National figures indicating COVID-19 surges since the first positive case in January 2020

In responding to the pandemic, criminal justice agencies throughout the United States have had to balance the interests of public health with the interests of public safety. Many law enforcement agencies increased the use of citations in lieu of arrests, particularly for lower-level offenses. They also limited enforcement of certain types of offenses, such as traffic violations. These responses reduced the number of interactions between police and the public, as well as the number of people entering jails. Most courts underwent a significant shift toward remote hearings and continued cases for extended periods. Jurisdictions throughout the country enacted policies to limit pretrial detention, including presumptive release on recognizance for broad classes of offenses. Community corrections agencies transitioned from in-person reporting to remote or limited reporting to protect their staff and supervisees. In many cases, closures of community supports, such as substance use treatment and job skill development, required adjustments to community supervision plans.4

Correctional institutions faced an even greater challenge in maintaining this balance. The confined nature of their settings, their congregate environments, and the high prevalence of medical vulnerabilities of individuals in custody all heighten not only the potential for COVID-19 to spread within facilities but also the severity of the disease among those infected.5 Toward the end of 2020, confirmed COVID-19 case rates in prisons were nearly four times the national rate, and some of the largest clusters of cases in the United States have occurred inside correctional facilities. In addition, the death rates in prison are higher than statewide rates, and this disproportionate impact does not appear to be going away.6 By April 3, 2021, individuals in custody contracted the virus at a rate over three times the general population and died from COVID-19 at a rate of two-and-a-half deaths to every one death in the community.7 In response to these challenges, some state systems sought to increase the number of individuals released from correctional facilities by executive orders, state legislation, or other means. At the local level, many departments underwent shifts, such as reducing custodial arrests and increasing release on recognizance.8 Other jurisdictions did not make such concerted efforts to reduce the number of incarcerated individuals.

In addition to these responses, correctional systems also acted to mitigate the risk of infection for those who work and are incarcerated inside the facilities. Responses inside correctional facilities included increasing space between people in custody by opening up closed areas of facilities or creating makeshift housing areas, staggering meal times and recreation, limiting movement outside of housing units, stopping visitation and programming that required any outside staff to enter facilities, and establishing quarantine periods at intake.9,10 Some states implemented mass testing in their prison systems11, and most required PPE compliance from certain incarcerated people as well as staff.12

The pandemic also had a profound effect on behavioral health in the criminal justice system, both with regard to the incidence of mental illness and substance use disorders among justice-involved people, and the availability and accessibility of treatment services. This is significant, as behavioral health needs are already disproportionately prevalent in the criminal justice system.13 The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that people with serious mental illness are booked into jails about two million times per year, and about two in five incarcerated individuals have a history of mental illness.14 The pandemic exacerbated the incidence and severity of these illnesses. Researchers found that symptoms of anxiety and depression increased in the spring of 2020 compared to the same time in 2019,15 and the CDC reported the number of drug overdose deaths in 2020 was the highest number ever recorded.16 This increase is compounded by the fact that the pandemic forced temporary or permanent closures of treatment services, impeding the ability for individuals to get needed treatment.17

Lastly, crime rates during the pandemic changed in a variety of ways. National violent crime rates rose during 2020, while national property crime rates continued a 20-year decline.18 While some offense types increased from 2020 to 2021 (aggravated and gun assaults), others decreased (burglary, larceny, and drug offenses).19 Homicide rates also fluctuated but were generally higher than in recent years, rising by 49 percent from the first quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2020, then declining from a peak in the summer of 2020. Overall, violent crime rates in 2020 remained lower than two decades prior with a difference of over 100 fewer violent incidents per 100,000 in 2020 compared to 2000.20

Endnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 5). CDC museum COVID-19 timeline.

- Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest maps, dates, and death counts. (2022, February 28). The New York Times.

- National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice. (2020, December). Experience to action: Reshaping criminal justice after COVID-19. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

- Montoya-Barthelemy, A. G., Lee, C. D., Cundiff, D. R., & Smith, E. B. (2020). COVID-19 and the correctional environment: The American prison as a focal point for public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(6), 888-891.

- Schnepel, K. T. (2020). COVID-19 in U.S. state and federal prisons. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

- Marquez, N., Ward, J. A., Parish, K., Saloner, B., and Dolovich, S. (2021). COVID-19 incidence and mortality in federal and state prisons compared with the U.S. population, April 5, 2020, to April 3, 2021. Journal of the American Medical Association, 326(18), 1865-1867.

- Prison Policy Initiative. (2022, February 25). The most significant criminal justice policy changes from the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. (2020, March 13). Federal Bureau of Prisons COVID-19 action plan: Agency-wide modified operations.

- Ridderbusch, K. (2021, October). COVID precautions put more prisoners in isolation. It can mean long-term health woes. NPR.

- Schnepel, K.T., Abaroa-Ellison, J., Jemison, E., & Engel, L. (2021). COVID-19 testing in state prisons. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

- Widra, E. & Herring, T. (2020, August 14). Half of states fail to require mask use by correctional staff. Prison Policy Initiative.

- Steadman, H. J., Osher, F. C., Robbins, P. C., Case, B., & Samuels, S. (2009). Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric Services 60(6), 761-765.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Mental illness and the criminal justice system.

- Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Rajaratnam, S. M. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24-30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049-1057.

- Farley, E., Engel, L. & Jemison, E. (2021). COVID-19 and the changing landscape of substance use disorder treatment. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

- Id.

- United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2021, December). Crime in the United States, 2021.

- Rosenfeld. R., & Lopez, E. (2021). Pandemic, social unrest, and crime in U.S. Cities. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

- Violent crime rates in 2000 were near 500 per 100,000 whereas 2020 rates were under 400 per 100,000. See Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer, https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend

This project was supported by Grant No. 2015-ZB-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Crime and Justice Institute (CJI), a division of Community Resources for Justice, works to improve public safety and the delivery of justice by providing nonpartisan technical assistance, research, and other services to improve outcomes across the spectrum of the adult and juvenile justice systems, from policing and pretrial through reentry. CJI provides direct technical assistance, assessment, implementation, research, data analysis, training, facilitation, and more. We take pride in our ability to improve evidence-based practices in public safety agencies and gain organizational acceptance of those practices. We create realistic implementation plans, put them into practice, and evaluate their effectiveness to enhance the sustainability of policies, practices, and interventions. Find out more at www.crj.org/cji.