System Impacts

Introduction

In addition to the quantitative data described above, CJI collected qualitative data in the form of interviews with justice system practitioners and stakeholders throughout the state. Each practitioner was forced to adjust to the extraordinary circumstances the pandemic created. Below is a summary of some of notable findings from these interviews, as they relate to several different segments of Nevada’s justice system.

Law Enforcement

- Departments focused their limited resources on more serious offenses

- Drug and mental health calls increased

- Officers reported a need for more behavioral health alternatives

A combination of changing crime rates, staffing shortages, and policy responses designed to protect public health impacted Nevada policing during the pandemic. In early 2020, statewide lockdowns, combined with reductions in tourism throughout Clark County and the rest of the state, contributed to a reduction in calls for service.57 This was met by staffing shortages brought about by large numbers of officers out sick due to the pandemic. In addition, law enforcement agencies introduced a range of practices and policies designed to limit unneeded in-person interactions, but they did so largely on an informal and unwritten basis. These included using citations whenever it was safe to do so, while reserving custodial arrests for individuals charged with committing serious offenses or allegedly engaging in activity that posed an immediate threat to public safety. These policies were motivated by a few different factors, including staffing shortages and a desire to protect officers and the public from contracting the virus during street encounters.

Law enforcement practices to reduce unneeded in-person contact were localized and department-specific. Some agencies triaged calls for service and primarily responded to those with a determined public safety flag (e.g., prioritizing calls involving a threat of injury over calls reporting a public nuisance), and referred calls that did not require immediate intervention to public health agencies. Other departments halted or delayed the execution of lower-level arrest warrants, particularly for misdemeanor offenses that did not jeopardize public safety.

In addition to the aforementioned departmental policies, state lawmakers passed legislation in June 2021 that heavily favored the use of citations for ordinance violations, most traffic violations, and many state misdemeanors, with the exception of violent crimes, stalking, or driving on a canceled or suspended license.58 Law enforcement officers continue to be restricted from issuing a citation if the violation is likely to continue or if there is an imminent threat of danger to another person or property. This increased discretion for law enforcement officers likely impacted the decline in court filings and prison admissions for low-level, nonviolent offenses.59

Another shift in law enforcement practices during the pandemic was related to calls for service where an individual displayed a behavioral health need. Stakeholders in Nevada shared that these kinds of calls increased during the pandemic. The state has a variety of mechanisms through which police officers can engage with individuals who have behavioral health needs in ways that are more likely to result in positive outcomes. These mechanisms include Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT), Mobile Outreach Safety Teams (MOST), Forensic Assessment Services Triage Teams (FASTT), and other programs. During the past few years, interest in CIT trainings and other programs has increased. However, during COVID-19, many of these trainings were canceled, postponed, or conducted virtually, which stakeholders generally believe is not as effective as in-person training. Moreover, the current capacity of most of these teams is limited and, as a result, they are often only able to respond to 40 to 50 percent of calls for service. This capacity was further reduced when some clinicians on these teams worked from home during the pandemic. Along with treatment providers having limited capacity due to social distancing or staffing issues, this made interactions with individuals in crisis and referrals to treatment more challenging. Interviewees felt strongly that in-person interactions are more effective at intervening in a crisis, but acknowledged that telehealth or virtual services are better than nothing.

Another change law enforcement experienced during the pandemic was an increase in calls for service to law enforcement for fatal and nonfatal drug overdoses. The Nevada Overdose Data to Action program reported that accidental drug overdose deaths increased by 55 percent between 2019 and 2020.60 Stakeholders shared that this was likely due to an increase in fentanyl use, which is in line with national trends. Nationwide, there were more overdose deaths related to fentanyl in one year from April 2020 to April 2021 than overdose deaths caused by all types of drugs combined in the entirety of 2016, according to the CDC and the National Center for Health Statistics.61 Nevada has leave-behind programs, including in Washoe County, where law enforcement and EMS can leave naloxone kits for overdose treatment in situations where they think opioids may be used. For example, if they have responded to an overdose and have reasons to believe it may happen again, they can leave naloxone kits with the individual who experienced the overdose or with family or friends to reverse potential future overdoses. While the pandemic created an even greater need for resources to combat overdoses, the use and availability of naloxone has been inconsistent across the state, stemming from officers’ individual aversion to carrying it and a lack of funding for widespread access across the state.

Apart from the tools like naloxone, law enforcement typically has the authority to bring an individual who may have committed an offense but is experiencing mental health or substance use issues to a place where they can get treatment, medication, and other services. These types of centers include the Carson Tahoe Mallory Behavioral Health Crisis Center, where individuals can receive care without having to go to the emergency department or be booked into jail. Stakeholders shared that there are not enough places like this and that transporting individuals to one of the few centers can be difficult. During the pandemic, this became even more challenging due to treatment centers limiting the number of individuals for whom they could provide beds or treatment. Treatment providers had to balance mitigation methods such as social distancing with providing treatment to individuals in crisis.

Prosecution

- District attorneys prioritized prosecution of violent and sex offenses and showed some increased flexibility concerning dispositions of certain drug and property offenses

Similar to law enforcement, the pandemic forced prosecutors’ offices, to varying extents, to focus their resources on the most serious cases. During the first wave of the pandemic in spring and summer of 2020, the Clark County District Attorney’s Office established a special unit to screen cases for prosecution, prioritizing those that involved injury or harm to others. Interviews revealed that other counties made efforts to prioritize cases involving an imminent public safety risk, though they did not establish a separate unit. Accordingly, both the AOC and Eighth Judicial District felony case filing data show the largest percentage of cases filed during the pandemic were for person-based offenses. While there was a clear shift in focus, prosecutors’ offices did not establish formal policies; the changes occurred predominantly through unofficial policy or at the discretion of individual prosecutors and judges.

Practitioners also generally agreed that prosecutors displayed increased flexibility concerning plea agreements for nonviolent and non-sex offenses. Interviews revealed this was largely driven by an effort to dispose of cases quickly in light of the backlog and reduce density during a pandemic by reserving prison and jail beds for individuals who pose a risk to public safety. This increased flexibility included offering more probationary sentences to incentivize pleas, which is reflected in court data. For example, in the Eighth Judicial District Court, more than 58 percent of drug dispositions were sentenced to probation, compared to 45 percent for drug dispositions sentenced to probation before the pandemic. The percentages of cases where individuals were sentenced to probation also increased for property and person offenses, but to a lesser degree. For sex offenses, the use of probation was similar before and during the pandemic.

Courts

- A widespread shift to remote practice paid dividends in efficiency but presents risks concerning a backlog and the viability of some convictions

- Continuances and closures added to existing court backlogs

- Specialty Courts recorded a higher incidence of behavioral health issues and reduced completion rates

As the pandemic began, most Nevada courts limited in-person court proceedings. The state’s largest judicial districts in the Eighth and Second Judicial District Courts closed in-person operations between April and September of 2020, utilizing remote participation where feasible. Since June 2021, both courts have fully reopened and resumed a more regular schedule, but they still maintain remote hearings for certain types of cases or proceedings.62 In addition to physical court closures and remote hearings, all courts, to varying degrees, continued cases to avoid compromising the health of individuals involved in court proceedings. Stakeholders shared that courts attempted to focus continuances largely on cases where the defendant remained out of custody, but many in-custody cases were also delayed.

Justice courts never completely shut down, due to the immediate need to arraign newly arrested people; however, AOC data showed that pending caseloads grew as processes slowed.

Stakeholders noted some benefits and disadvantages of remote proceedings. On one hand, remote proceedings allowed for physical separation among the parties at a time when it was critical for public health. Attorneys and judges noted the benefits of having a more flexible schedule, as well as the elimination of wasted time waiting for cases to be called. Discussion with individuals from the impacted community revealed a preference for remote hearings in reducing some of the barriers to getting to court, including work, childcare, transportation, and, in rural areas, distance.

On the other hand, several interviewees discussed challenges inherent to remote hearings. Defense attorneys expressed frustration with being unable to speak to their clients directly before, during, or after a hearing, which they said is critical to preparing a defense. Both prosecutors and defense attorneys expressed concerns around introducing testimonial evidence over a remote session, believing that some of the persuasive value of the evidence was lost. Some defense attorneys believed that during remote sentencing hearings (as well as parole or probation violation hearings), the lack of physical proximity between judges and the defendant could sometimes lead to a tougher sentence, or a higher likelihood of revocation. Some practitioners in rural areas suggested a centralized location where people could appear to testify that might be more geographically convenient than the court of relevant jurisdiction, such as a library or other government building.

In addition to shifting to remote proceedings, the pandemic significantly hampered the process of preparing a criminal case. Defense attorneys reported that collecting evidence, finding and interviewing witnesses and strategizing with clients made it difficult to adequately represent their clients. Similarly, prosecutors often needed to wait longer for evidence to arrive, due to pandemic-related delays at the state lab, as well as challenges with coordinating witnesses. Prosecutors and victim witness advocates reported difficulties in connecting with crime victims and facilitating their appearance in court, especially in rural areas. This resulted in cases taking longer to go through the court process. As described earlier, data from the AOC show the number of felony cases older than a year increased by 370 percent between 2019 and 2020.

While closures and continuances were a necessary response to the pandemic, delayed dispositions have also created challenges for the courts. One that has persisted is the growing number of unresolved cases added to a backlog that is straining resources, especially in Clark County. (Courts around the country are facing this problem, according to a report from the National Center for State Courts.63) Of the more than 23,000 cases filed in Nevada’s Eighth Judicial District (primarily Clark County) between July 2018 and June 2021, 5,509 had yet to be disposed by August 2021.64 Of the pending cases, 79 percent involved felony charges. Roughly 1,650, or 38 percent, of those pending felony cases were person-based offenses, with 244 categorized as either murder, attempted murder, or conspiracy to commit murder. Even before the pandemic, prosecutors and defense attorneys in Clark County had heavy caseloads. After the pandemic-related continuances, several reported their caseloads increased significantly. The number of case filings and open cases are stark compared to estimates from the Second Judicial District (Washoe County). Between July 2018 and June 2021, those courts saw just over 5,000 cases filed. Exploring open caseloads as of June 30 of each year, data showed that the Second Judicial District’s pending caseloads were notably lower in 2020, with 428 open cases compared to the 550 open case average from the two prior years. As of June 30, 2021, however, there were 709 open cases in the Second Judicial District, 78 percent of which were felony filings. Still, in Washoe County and the rural counties, caseloads were a less significant issue, and practitioners there generally reported optimism that the courts can catch up and return to the normal flow of cases during 2022.

To alleviate the backlog, courts began implementing new policies to resolve cases faster, the first of which concerned modifications to criminal trial stacks. In the spring of 2021, court leadership in both Clark and Washoe counties implemented a new procedure for cases that were ready for trial. This involved a standing session with a minimum of six to 10 cases scheduled and strongly presumed to proceed, a higher number than before the policy was implemented. The court uses set factors to rank the scheduled cases in order of their readiness and suitability for trial, with the most significant factors being whether the defendant is currently incarcerated, and whether the defendant invoked their speedy trial rights at first appearance.65 There is widespread agreement in both counties that the new trial stacks have had a positive effect and accelerated the pace of dispositions.

In addition to these expedited trial sessions, the Eighth and Second Judicial District Courts, as well as some Justice Courts, have developed new ways to facilitate pretrial plea agreements. Courts have primarily done so by holding mandatory settlement conferences between the parties in cases that are 60 or fewer days from their scheduled trial date. Judges in Clark County who preside over such hearings report a high rate of resolution for such cases. Involved parties agree that the settlement conferences aid in expediting case resolutions, and at least one practitioner believes that this procedural step can lead to generally fairer dispositions than would be reached following a trial verdict.

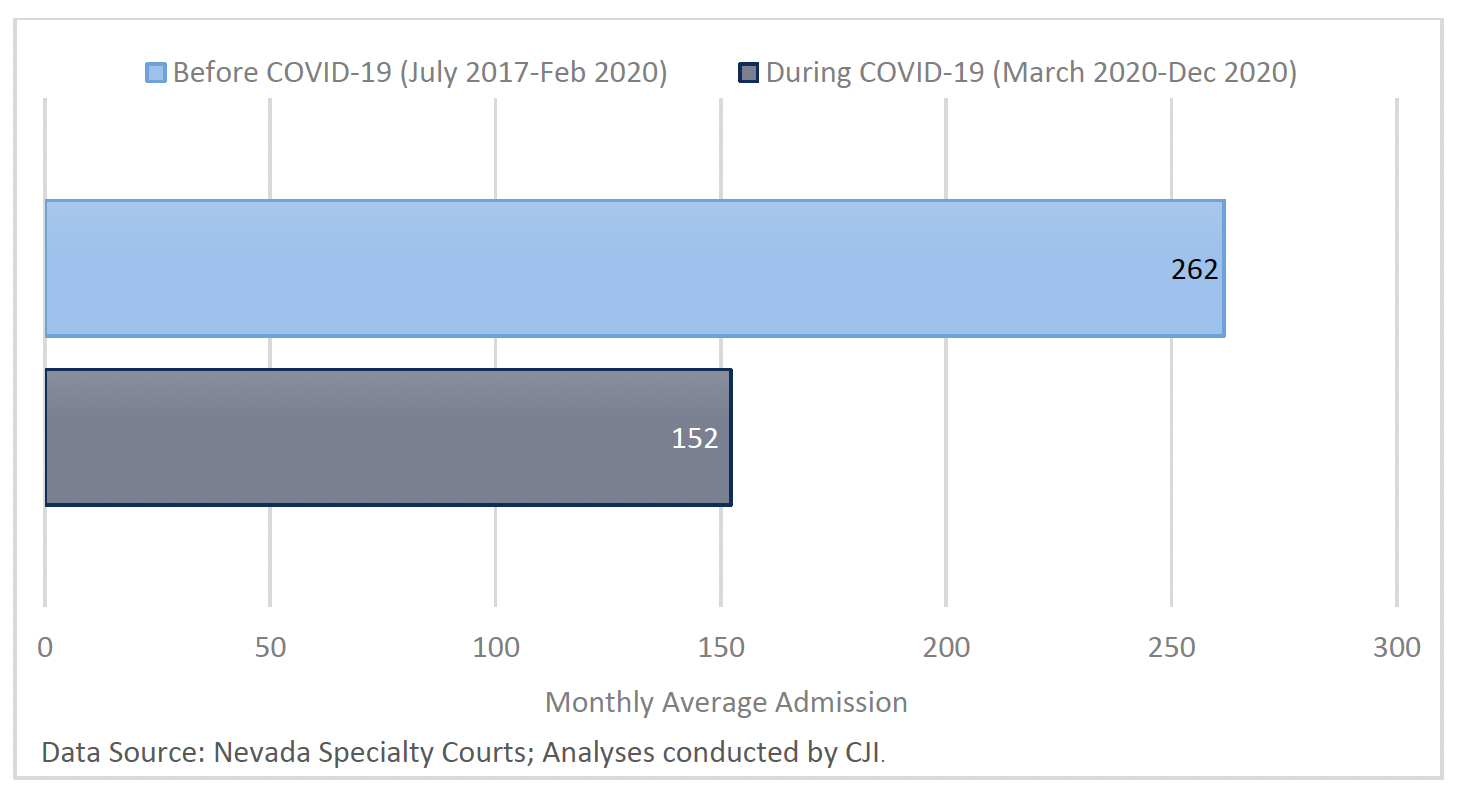

Lastly, beyond changed court processes, data show the pandemic brought shifts in the reliance on diverting individuals to Specialty Courts during the pandemic. During the pandemic, utilization of Specialty Courts decreased, with a 42 percent decline in average monthly admissions (see Figure 15). This was largely in step with decreased court filings overall. The reduced admissions to Specialty Court were particularly significant given the increase in percentage of those entering the programs who had behavioral health needs. During the pandemic, there was a 21 percent increase in the proportion of admissions with mental health histories, a 21 percent increase in those with prior substance use treatment, and a 6 percent increase in the proportion of individuals who were unemployed.

Figure 15. Specialty Courts’ average monthly admissions went down 42 percent during COVID-19

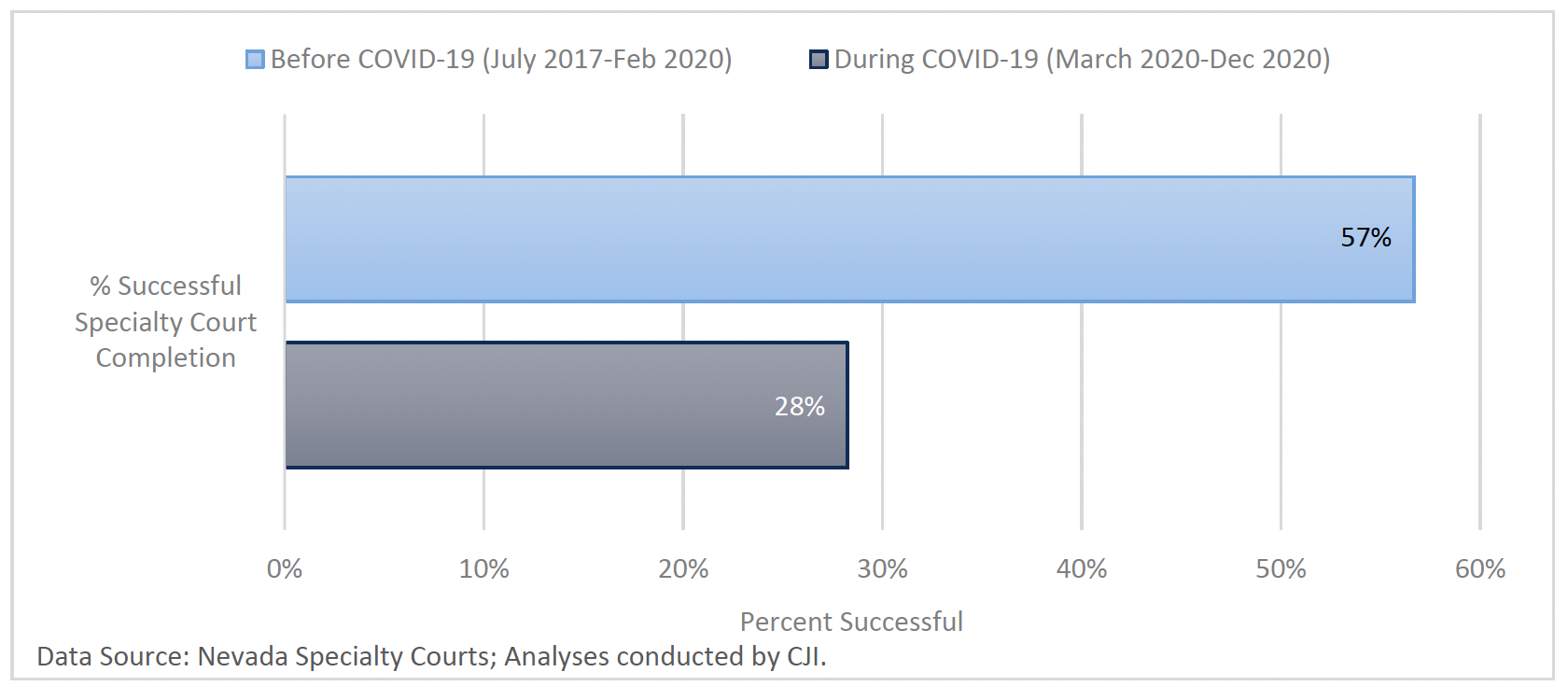

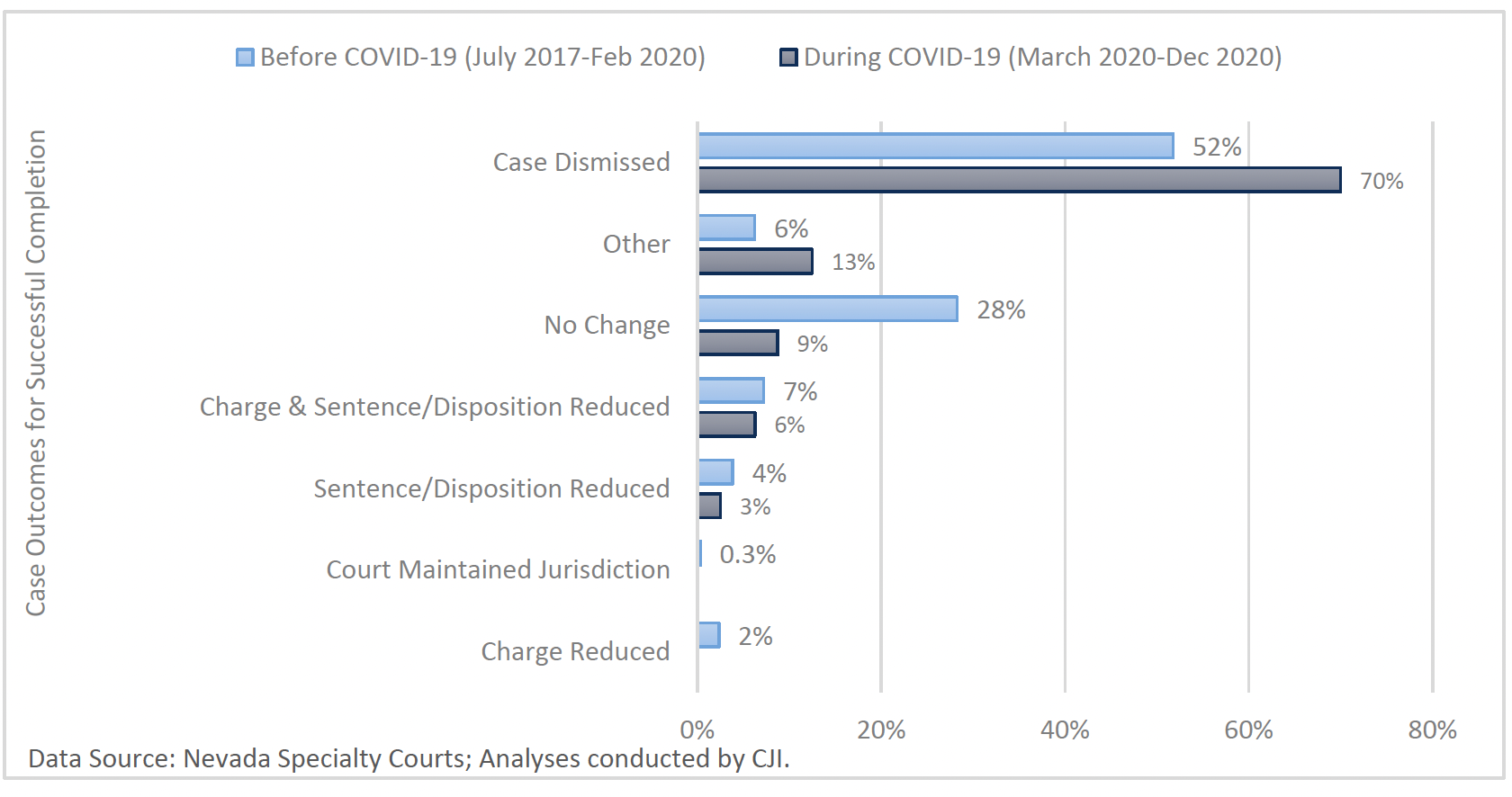

Aside from reduced admissions, the rate of successful completion of Specialty Court programs also dropped during COVID-19, outpacing the decline in admissions and dropping by half, to a success rate just under 30 percent (see Figure 16). Interviews indicated that staff noticed a sharp increase in absconding66 in the initial months of the pandemic, particularly among the high-risk and high-need population, but they reported that this did not remain the case for long. As for case outcomes among the smaller percentage of successful Specialty Court completions during COVID-19, case dismissals became increasingly common (see Figure 17).

Figure 16. The Specialty Court successful completion rate dropped 50 percent during COVID-19

Figure 17. A greater share of case dismissals are among those who successfully completed Specialty Court during COVID-19

Corrections

- NDOC collaborated with the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health to establish a “firewall strategy” that included screening processes, reduced exposure by limiting external contacts, and restricted movement within facilities

- The firewall strategy was not accompanied by any effort to reduce the population of NDOC facilities

- The implementation of CDC-recommended practices for the prevention of institutional virus transmission proved very challenging in a corrections setting

- Some of the implemented policies – including prolonged lockdowns, limited contact with external support systems, and reduced programming – had adverse effects on the mental health and wellbeing of incarcerated people

- With prison medical staff diverted to respond to COVID-19 patients, access to medical care and behavioral health support for the general population became more difficult

The firewall strategy

The Nevada Department of Corrections’ (NDOC) initial approach to protect its staff and incarcerated people from the spread of COVID-19 was referred to as the firewall strategy. It was developed and implemented in March 2020 by NDOC administrators in conjunction with staff from the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH). As a result of this collaboration, NDOC established a new institutional admissions procedure and staff screening process, consisting of temperature checks, a verbal COVID-19 assistance questionnaire, visual symptoms observation, mandated nose and mouth coverings, and a mandatory reporting requirement for any staff member or incarcerated person who displayed symptoms.67 If during one of these screenings an incarcerated person was symptomatic or tested positive, they were initially moved to isolation for 14 days, a period that was later changed to 10 days following updated CDC policy guidance. If the symptomatic or positive person was in a dorm setting, the other individuals in the dorm would be monitored for symptoms but not tested. Likewise, any staff member who was positive or symptomatic at screening would be required to quarantine for the 14-day, and later 10-day, period. The strategy also prohibited all outsiders from coming into institutions to avoid potentially exposing incarcerated individuals. This resulted in stops to all visitation, nearly all in-person programming, and a presumptive halt of all but the most critical inter-facility transfers. The firewall strategy also restricted movement within the facilities in the form of lockdowns of incarcerated people. There was also a severe reduction of recreation time, religious services, and prison libraries.

Challenges with implementation

This firewall strategy proved difficult to implement in a corrections setting and created several challenges within institutions. First, the necessity to keep certain classes of incarcerated individuals separate from others – for example, those who are at a high risk of engaging in violent misconduct – limited opportunities to achieve meaningful physical separation. Second, a lack of information about the pandemic or the rationale for the policy changes created an environment of distrust and sometimes noncompliance among people in custody. Interviews suggest that requests for information by incarcerated people through inmate request forms (known as Kites) received inconsistent replies and sometimes went unanswered. Interviewees also noted that their confusion was exacerbated by observing practices that conflicted with policies such as the fact that some transfers between facilities still occurred and mask wearing was not consistently observed across the facilities, both by staff and individuals in custody.68 Third, the staffing shortages NDOC experienced throughout the pandemic presented an additional challenge to the effective implementation of the policies. In January of 2022, prison officials stated that there was a 25 percent vacancy rate among custody staff, which was a significant increase from 9 percent at the start of the pandemic.69

Impact of policies on incarcerated individuals

While conceived to protect the physical health of people in custody, some pandemic policies had adverse impacts on the mental health of people incarcerated. One example was the significant amount of time spent in lockdown. Interviews with stakeholders indicated that the use of lockdown periods increased significantly during the pandemic, along with access to recreation, work detail, programming, religious services, and law libraries. Some interviewees reported that individuals got a total of six or seven hours of access to outside space across a period of 10 months.

This isolation was compounded by the halt of in-person visitation. NDOC suspended all visitation between March 2020 and May 2021, and it has since been discontinued in response to flare-ups of the virus, with one statewide suspension as recent as January 6, 2022.70 To compensate for the absence of visitation, NDOC allowed two free phone calls per week.71 However, interviews revealed that there was high demand for the phones, often making them unavailable, and that call times were scheduled during unusual hours, often in the middle of the night. This lack of connection to the outside is significant, as research shows that pro-social behavior achieved through programming or existing relationships is an important element of recidivism reduction.72 Studies have shown that visits are integral in promoting an incarcerated person’s mental health by reducing stress, maintaining family bonds, and supporting a connection to their larger community.73,74

In addition to the halt of visitation, the pandemic rendered in-person programming unavailable. NDOC stopped nearly all in-person programming for at least nine months (from March 2020 to April 2021), with some types of programming taking over a year to resume.75 For instance, NDOC halted educational programming in March 2020 and in the majority of facilities it did not return for over 16 months. There was an effort at some facilities to provide people with packets to complete toward their educational certificate, in lieu of in person classes. However, credit for packet completion was not always awarded, due to an inability to discern whether people were themselves completing the packet assignment.

An additional collateral consequence of the limited programming was its potential to extend prison stays for individuals in custody. Under Nevada law, individuals who committed an offense on or after July 17, 1997, are permitted to earn 10 days of credit per month for meritorious behavior, in addition to a lump sum of 60 days of credit for educational programming, 90 days for a high school diploma, and 120 days for completing their first Associate Degree.76 Without programming opportunities, individuals in custody could not participate or earn credits to reduce their sentences. Because credits may not be earned by people convicted of more serious Category A or B felonies, the absence of credits only adversely impacted those convicted of Category C, D, or E felonies.77 The Legislature targeted these concerns through passage of AB 241 in the 2021 legislative session. The bill retroactively allotted individuals incarcerated during the pandemic an additional 5 days per month not to exceed 60 total days total. The purpose of the legislation was to in part compensate for these loss of programming credits.

Access to medical care

In addition to the challenges noted above, access to medical care for incarcerated people during the pandemic was reduced. In more normal times, people connected with medical providers by submitting an inmate request form and medical staff approved or disapproved the request and determined follow up care.78 NDOC staff shared that in some facilities, medical staff had to largely shift away from chronic care to focus on COVID-19 screening. Staff also had to triage which medical concerns were the most serious to address, which resulted in many Kites going unanswered or unaddressed for months. During the pandemic, NDOC contracted with nursing staff to help with COVID-19 testing, which allowed other medical staff to continue providing other services. Finally, NDOC continued to charge incarcerated individuals for medical care, a cost that most states across the country waived during the pandemic.79

Lastly, while the Department made all staff and those in custody eligible for vaccination as soon as it was available, access to the vaccines and trust in them remains a challenge across the state’s prisons. Interviews revealed that incarcerated people are required to submit a vaccination request, and that the timeline from submitting the request to being administered a vaccine was sometimes over a month. As of October 20, 2021, NDOC reported that 64.74 percent of incarcerated individuals were fully vaccinated.80

Behavioral health in correctional institutions

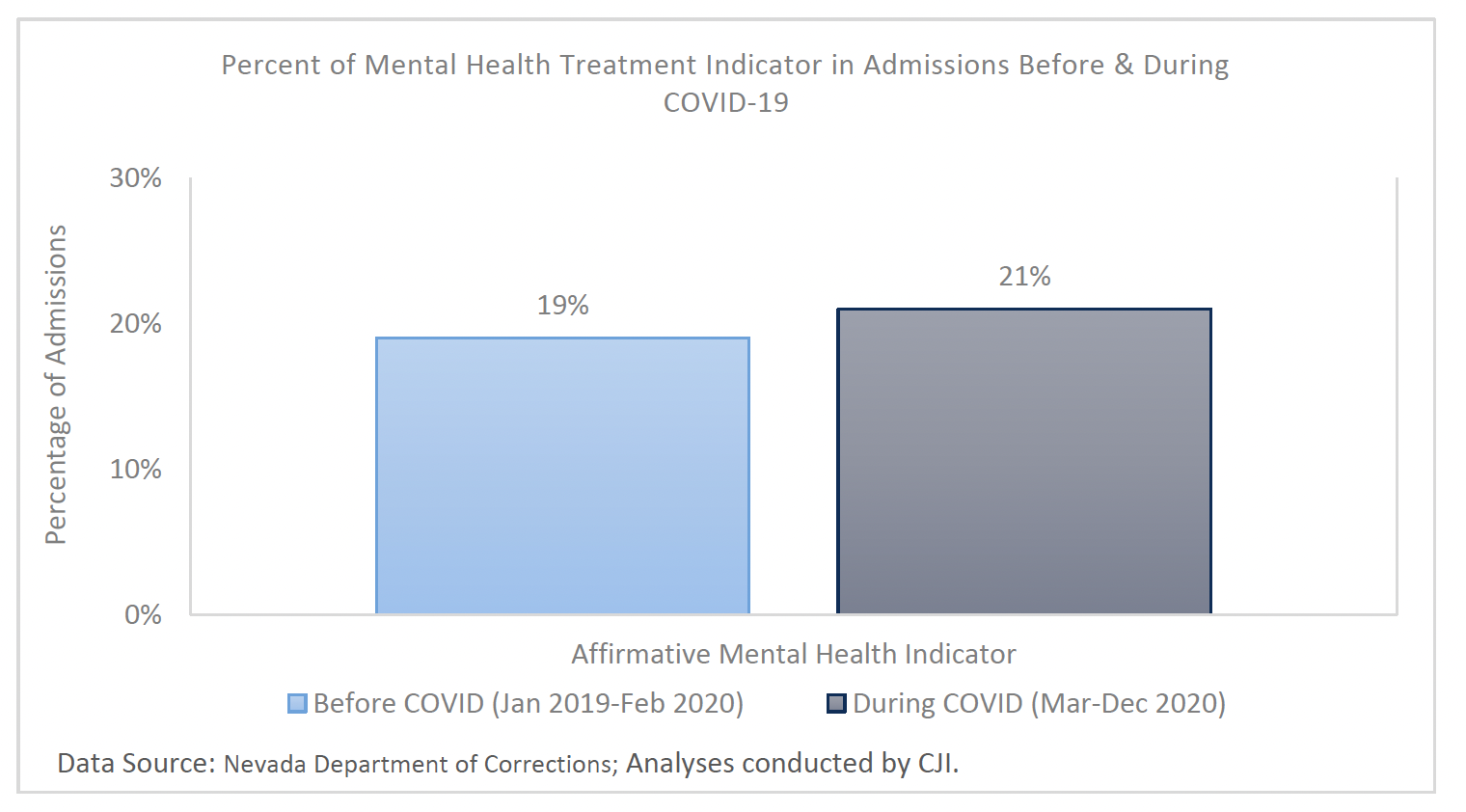

The high prevalence of behavioral health needs among individuals in custody increased during the pandemic. The percent of individuals in need of mental health treatment and admitted to NDOC custody during COVID-19 (March through December 2020) was higher than the preceding 14 months (see Figure 18). NDOC data showed that just over 18 percent of people in NDOC custody on May 30, 2020, had affirmative mental health indicators; a year later this was up to 19 percent. For both years, over 90 percent of those with affirmative mental health indicators were further classified as having “mild impairment” and needing follow-up mental health services but not necessitating custody placements.

Figure 18. Slight increase in the portion of NDOC admissions indicating prior mental health treatment at admissions

These classification percentages are significant in that during the pandemic those in specific mental health housing received continued treatment while those whose treatment was classified as follow-up received limited services as staff was diverted to COVID-19 care. Nevada’s correctional system has housing units specifically for individuals with mental health or substance use disorders, including therapeutic communities in NDOC facilities. Interviews revealed that these specialty units were able to maintain most of their regular programming because it did not require individuals to move throughout the facility. However, while those who were already in these units were able to stay engaged in programming and services, stakeholders shared that it was difficult to introduce new individuals. Facilities throughout the state were limiting transfers, and intake facilities lack the capacity for therapeutic communities. Thus, individuals entering the prison system during the pandemic who may have been eligible for such housing could not participate. As a result, program numbers decreased for these units, and fewer individuals were able to take advantage of the services offered in them. Concerning programming overall, research indicates that access to and participation in counseling and other programs is crucial to the mental health and well-being of those in custody, especially during times of heightened stress.81

Looking specifically at mental health services in jails, it was also more difficult to maintain the status quo. In the Las Vegas Municipal Jail, for example, wellness fairs with community partners are typically offered for incarcerated individuals to connect with post-release job opportunities. The jail also usually holds AA meetings but stopped both the wellness fairs and AA meetings for several months due to growing restrictions. Before COVID-19, if an incarcerated individual was experiencing psychosis and refusing treatment, jails had the means to send them to the hospital. However, during the pandemic, hospitals had stricter capacity limits, so it was difficult to provide care for individuals in crisis. Group therapy sessions were also suspended for a time, including self-regulation, values clarification, and anger management. In some areas of the state, programs such as MOST and FASTT are able to connect incarcerated individuals to services by going to jails and meeting with individuals who will be released in the near future. Interviewees expressed that during the pandemic, some of these teams were unable to enter the jails and therefore they could not easily provide needed services to individuals preparing to release from incarceration.

Typically, individuals entering NDOC custody are assessed for their mental health status to identify any impairment, medication, or therapy needs. Based on this evaluation, they may share recommendations with mental health staff or refer the individual for further treatment and evaluation when needed. The recommendations may result in certain housing or programming assignments, or transfer to another institution, depending on the capacity for a facility to serve the individual.82 At the height of NDOC COVID-19 surges, instead of the full evaluation process, mental health staff initiated door-to-door welfare checks to see how incarcerated individuals were tolerating the lockdown. While this practice enabled staff to assess the needs of incarcerated individuals, it also presented challenges in terms of privacy and willingness for individuals to open up and express needs. In addition, stakeholders with lived experience in the justice system shared that these checks did not happen with frequency or regularity.

Reentry

A key part of reducing the number of individuals coming into the justice system is ensuring that individuals leaving incarceration have access to appropriate reentry supports. During the pandemic, staff shortages presented a significant barrier to preparing for individuals’ reentry from NDOC facilities. Nevada statute requires NPP and NDOC to collaborate in developing a reentry plan six months prior to an individual’s release on parole.83 This has been extended by practice to apply to all individuals being released from NDOC custody and not just those being released to parole. The plan focuses primarily on establishing housing opportunities for individuals, but it also sets up necessary treatment and job readiness programming. NDOC staff meet regularly with individuals in custody to develop the plan. As noted above, access to individuals in custody was limited during the pandemic as housing units were quarantined and facilities did not have enough staff to escort individuals to staff offices. Additionally, NPP staff did not work in the facilities during the pandemic, and their role in facilitating contact with parole services prior to release was unavailable. Interviews noted many situations where the Parole Board approved an individual for parole, but because the person was unable to find housing, their reentry plan was not approved, and they were not released from NDOC custody. The data on how many individuals currently in prison who have been granted parole were unavailable for analysis.

Aside from challenges in developing the reentry plan, the pandemic made finding transitional housing significantly more challenging. Prior to COVID-19, transitional housing was already limited, and during the pandemic these opportunities further diminished. Additionally, anywhere that did have capacity required a two-week quarantine before entry, raising the unanswered question of where a person released from prison or jail should go in the interim.

Lastly, state statute requires NDOC to provide individuals leaving prison with identification, clothing, transportation, Medicaid and Medicare enrollment paperwork, and a 30-day supply of medication if they were receiving it while in custody.84 In addition to these items, during the pandemic, NDOC administered a COVID-19 test upon release. This policy ideally would allow individuals in custody to return to their family or other housing arrangements with proof they were not carrying the virus; however, interviewees noted that individuals rarely received their test results prior to release.

Community Supervision

- Due to reduced staffing and a desire to reduce in-person contact, Nevada Parole and Probation (NPP) shifted to a more remote supervision model, including online and phone check-ins and fewer home visits

- NPP focused its resources on higher risk supervisees – in line with national best practices – by reserving closer, more frequent supervision for those with demonstrated needs for closer surveillance

COVID-19 had a significant impact on how Nevada’s Division of Parole and Probation (NPP) operated. Supervision traditionally required regular in-person check-ins, largely occurring at NPP Field Offices. At each of these check-ins, a supervision officer would review a monthly worksheet with the individual they were supervising, administer necessary drug tests, and generally assesses how the person doing with completion of and adhering to their supervision conditions. In addition to these check-ins, officers also conducted home check-ins where they visited the individual’s residence. Following state-wide orders prohibiting or disfavoring in-person activities to maximize social distancing, these in-person meetings were more difficult to hold, and NPP transitioned to contactless supervision for most supervisees. While NPP already had remote supervision for its lowest category of supervisees, the transition to virtual supervision for its entire population was a significant change.

Supervision officers responded to this shift in a variety of ways. Some cited going remote as the largest challenge during the pandemic, feeling that it was an inadequate replacement for in-person meetings and less effective at assessing compliance. They noted concerns over whether individuals on supervision were exploiting the pandemic and citing symptoms of COVID-19 as a rationale for noncompliance.

Others applauded the technical improvements made during COVID-19 without diminishing the quality or effectiveness of supervision. Three out of four survey respondents noted the utility of electronic report submission and, for their supervisees, the utility of remote court or counseling sessions.

Likewise, feedback from individuals on supervision expressed that virtual check-ins created substantially more flexibility. It allowed them to stay connected with supervising officers without experiencing the challenges they did before COVID-19, including travelling to the office, interrupting a work schedule, and inability to get child care, among others. Individuals on supervision indicated that getting to and from an office check-in were significant hurdles that made it difficult to maintain good communication with supervisors and sometimes led to missing meetings.

Another aspect of NPP’s work that was significantly impacted by the pandemic was the presence of agency staff within NDOC facilities to assist with release planning. Stakeholders reported that prior to COVID-19, NPP staff would regularly visit prisons to meet with incarcerated people and NDOC caseworkers to facilitate eventual release. Since the onset of the pandemic, this work has largely been put on hold, and a system has not been created to allow such visits to occur remotely.

Similar to the added flexibility surrounding check-ins, during the pandemic NPP officers increasingly used discretion in responding to violations. This discretion was supplemented with a reduction in in-home residence checks and temporary halts of drug testing. Further, both the courts and NPP gave the directive to reserve revocation for serious misconduct; surveyed officers overwhelmingly agreed that their time and resources were spent on more serious offenses during COVID-19. Despite focusing on serious offenses, when asked about the most common violations observed during COVID-19, surveyed officers still overwhelmingly reported substance use-related activity driving revocations. This was particularly true for violations that did not involve a new charge, with 66 percent of officer responses referencing some aspect related to substance use, ranging from alcohol violations to controlled substance relapse as the most common violation that did not involve a new charge observed during the pandemic. This was also true for new crime violations during COVID-19, with nearly one in three survey entries citing possession of a controlled substance as a most common new criminal offense.

Given the emphasis of focusing time and resources on serious misconduct, surveyed officers reported a decline in supervisee revocations during the pandemic, despite filing a similar number of violation or incident reports as before COVID-19. Officers shared that if someone was consistently checking in and their supervisor knew how to get in touch with them, officers were willing to work through any setbacks and barriers using the graduated sanctions matrix.85 Discretion, with the clearly identified goal of keeping individuals out of prison unless they presented a public safety threat, allowed officers to think critically about misconduct and evaluate the appropriate response using the graduated matrix as a resource. Data on NDOC admissions during COVID-19 offer additional evidence of such practices, showing a 26 percent decline in average monthly admissions of individuals with parole violations that did not involve a new conviction alongside a 30 percent decline in admissions for probation violations that did not involve a new conviction, with 25 to 33 fewer admissions each month, respectively (see Figure 7). This trend is also supported by data from the Eighth Judicial District, Nevada’s largest district. Among cases with probation revocation hearings dates before COVID-19, 65 percent were revoked. For cases with probation revocation hearings during COVID-19, 61 percent were revoked. Despite a larger share of pending probation hearings, the percentage of cases where the probation was revoked after a final hearing further decreased to 36 percent during the first six months of 2021. Furthermore, during the first half of 2021, a greater percentage of hearings resulted in probation being reinstated compared to being revoked, which was not found before or during the pandemic.

Despite the reduction in violations that did not involve a new conviction occurring during the pandemic, there was still a sizeable number of individuals serving time in NDOC custody for such violations (e.g., technical violations or absconding). As of May 31, 2021, 1,928 individuals were in NDOC custody for a violation of either parole or probation without new convictions, more than half for nonviolent prior offenses, like property (31 percent), drug (12 percent), or other offenses (12 percent).86

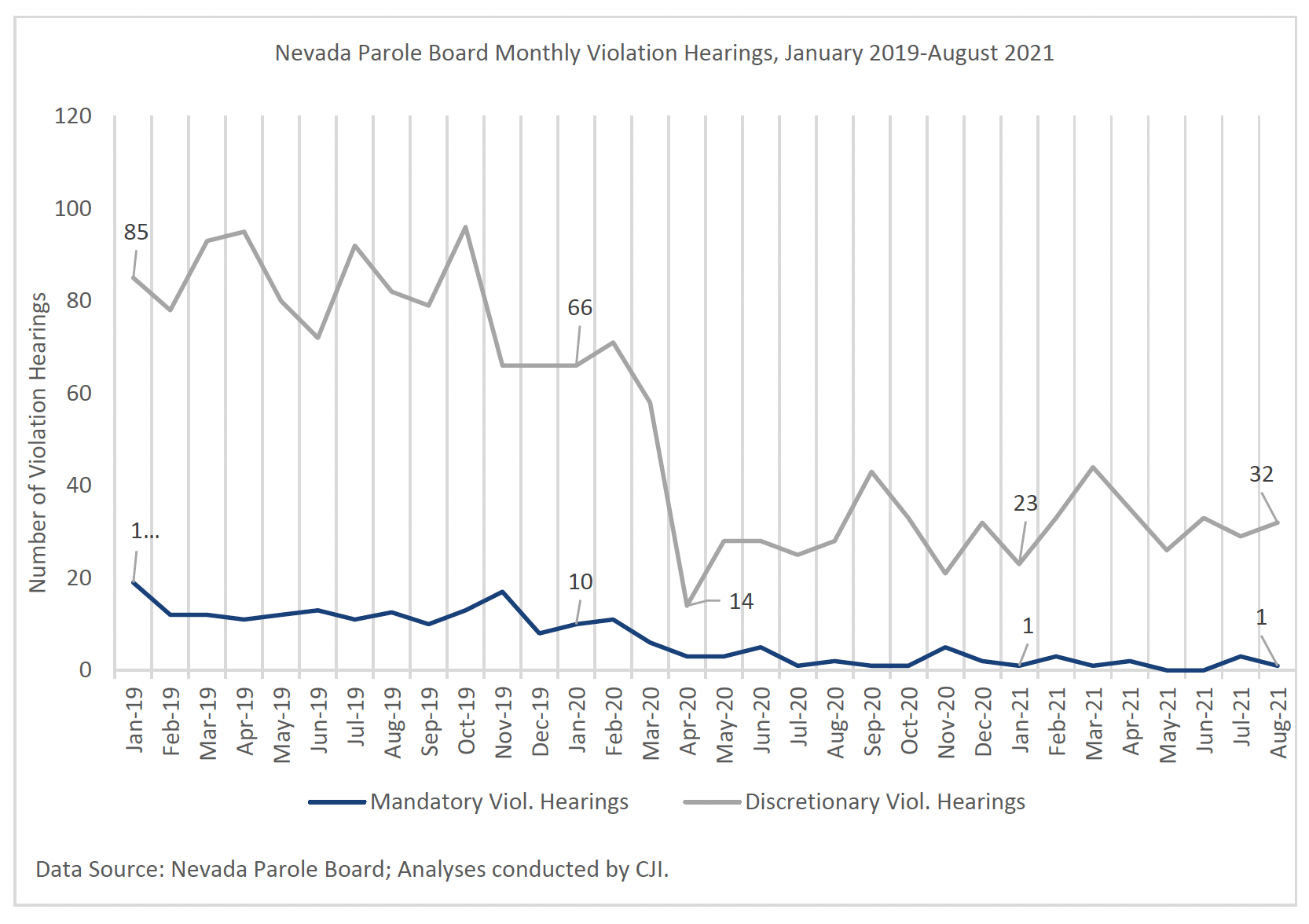

As for parole violation hearings, the Parole Board heard over 60 percent fewer cases during COVID-19 than in the 14 months prior (see Table 1), a difference of over 50 fewer parole violation hearings per month. This downward trend in number of violation hearings during COVID-19 continued to hold across the first half of 2021, with the average monthly number of violation hearings down nearly two-thirds from the 2019 average of 95 hearings per month to just over 30 (see Figure 19).87 Interviews revealed that COVID-19 forced previously in-person parole violation hearings to go remote. The data findings, however, suggest that violations are occurring less frequently, and additional hearings may be unnecessary at this time, especially when roughly 80 percent of all violation hearings, regardless of timing, involved cases designated as “moderate risk” and only 2 percent involved “high risk” cases.

Figure 19. Parole violation hearings remained low after April 2020

Despite fewer parole violation hearings both during COVID-19 and over the first half of 2021, revocation rates increased in both periods. For instance, the estimated revocation rate for parole violation hearings before COVID-19 was around 74 percent; during COVID-19 parole revocations increased to 86 percent of violations and held at over 85 percent well into 2021. The higher revocation rates were clear across all risk levels both during COVID-19 and into 2021; however, a closer look at the offense types processed during these different timeframes showed a greater share of violation hearings for violent offenses during COVID-19. These more serious offense types were likely a contributor to the observed growth in revocation rates despite fewer hearings. Interviews revealed that defense counsel felt the new remote style for parole violation hearings resulted in worse outcomes for their defendants.

Behavioral health for individuals on community supervision

Often, individuals who are on probation or parole are required to engage in behavioral health treatment as a condition of their supervision. Many treatment programs and services shut down or at least reduced capacity during the pandemic. In some cases, this was due to an attempt to social distance and in other cases it was because of challenges in remaining fully staffed. The difficulty in remaining open at full capacity was particularly the case for residential treatment providers, such as Ridge House, Vitality, and STEP2. Ridge House, for example, serves almost exclusively justice-involved clients, and the program typically receive many more applications than it has capacity to accept. It was very challenging for most residential treatment providers to continue offering services as usual while also maintaining social distancing and other COVID-19 protocols. Requiring quarantine upon admission was a positive step toward limiting the exposure to and spread of COVID-19 within these centers, but it did create many barriers to treatment provision and therefore the ability to serve the number of individuals in need of care. In some cases, this delayed an individual’s release onto parole or otherwise affected their ability to comply with their conditions of release.

While many residential facilities struggled to maintain their usual capacity, most community providers of non-residential behavioral health services were able to quickly transition to providing virtual services once the implications and dangers of the pandemic were apparent. The proliferation of telehealth services was helpful for individuals who faced barriers to entering and staying in treatment, such as lack of transportation or childcare. In addition, stakeholders shared that less stigma is typically associated with engaging in virtual behavioral health services. However, they also expressed that telehealth was difficult for individuals who did not have access to appropriate technology and for individuals with high levels of behavioral health need. This was particularly true for justice-involved individuals.

Endnotes

- The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (2020). The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department 2020 Annual Report.

- Assembly Bill 440.

- Assembly Bill 440.

- See Figure 3 and Figure 6.

- Dobbins, A. (2021, October 7). Drug overdose deaths increase in Nevada. Nevada Today.

- Keating, D., & Bernstein, L. (2021, November 17). 100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 12 months during the pandemic. The Washington Post.

- The extent of the shift to remote hearings varied by county; for example, despite some exceptions, such as suspending jury trials, the Third Judicial District Court otherwise continued in-person appearances for all essential cases and permitted in-person appearances for non-essential cases in March 2020. See: The Third Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada, Administrative Order 20-01 (March 17, 2020).

- Court Statistics Project. (2022, January 12). 2020 Incoming Cases in State Courts.

- The Eighth Judicial District data file used for these analyses captured cases filed between July 2, 2018 to June 30, 2021. The latest disposition date is August 9, 2021.

- NRS § 178.556.

- Data findings support staff reports, showing a greater share of absconding as reason for Specialty Court failure during COVID-19.Before COVID-19, absconding accounted for around 16 percent of failure reasons; during COVID-19 it rose to more than 23 percent.

- State of Nevada Board of Prison Commissioners. (2020). [Board of State Prison Commissioners meeting minutes].

- 68 While the Governor issued a mask mandate across the state in April 2020, NDOC did not require staff wear masks until June 2020.

- 69 Rindels, M. (2022, January 25). With 1 in 4 officer jobs vacant, employees say prison staffing dangerously low. The Nevada Independent.

- 70 Nevada Department of Corrections (n.d.). Home [Facebook page]. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- 71 State of Nevada Department of Corrections. (2022, January 25). NDOC COVID-19 Updates.

- Duwe, G. (2017 June). The use and impact of correctional programming for inmates on pre- and post-release outcomes. National Institute of Justice.

- Minnesota Department of Corrections. The effects of prison visitation on offender recidivism. National Institute of Corrections.

- Multiple staffers at reentry services organizations reported observing significantly lower morale and a higher incidence of mental health issues among people exiting NDOC custody, and they feared that the difficult conditions inside facilities during the pandemic could have an adverse impact on future recidivism.

- There were effectively four categories of NDOC programs available to incarcerated people before the pandemic: educational, mental health-focused, reentry-focused, and drug treatment-focused, as required by the therapeutic communities statute. See NRS 209.4237. Almost all of these programs were shut down for extended periods during the pandemic, at least for months and in some cases for over one year. In some facilities, drug treatment programs run by NDOC staff were able to continue, but less frequently and with smaller class sizes.

- Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 209.4465

- Id.

- Nev. AR 600, https://doc.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/docnvgov/content/About/Administrative_Regulations/AR%20600%20-%20040811.pdf (last visited May 19, 2015)

- Herring, T. (2020, December 21). Prisons shouldn’t be charging medical co-pays – especially during a pandemic. Prison Policy Initiative.

- Nevada Department of Corrections. (2021, October 25). Board of Prison Commissions October 25, 2021 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8unzPsB5Vec

- Morgan, R. D., Kroner, D. G., Mills, J. F., Bauer, R. L., & Serna, C. (2014). Treating justice involved persons with mental illness: Preliminary evaluation of a comprehensive treatment program. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(7), 902-916.

- There was only one observation in 2020 or 2021 of “severe impairment” requiring special housing and ongoing treatment.

- NRS § 213.140.

- NRS § 209.511

- Over two-thirds of surveyed officers also reported increased use of graduated sanctions during COVID-19.

- The majority (n=1,182) were probation violations without new convictions, while 698 were violations without new convictions of discretionary parole. In both May 2020 and May 2019, there were similar distributions of non-conviction-related violators in NDOC custody – over 60 percent probation violations and under 40 percent parole violations – again, all violations unrelated to new convictions. COVID-19 does not appear to have impacted this distribution.

- It is worth noting that in any given year in the Parole Board data, a very small portion of parole violation hearings are mandatory, with discretionary hearings comprising around 90 percent of all hearings.

This project was supported by Grant No. 2015-ZB-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Crime and Justice Institute (CJI), a division of Community Resources for Justice, works to improve public safety and the delivery of justice by providing nonpartisan technical assistance, research, and other services to improve outcomes across the spectrum of the adult and juvenile justice systems, from policing and pretrial through reentry. CJI provides direct technical assistance, assessment, implementation, research, data analysis, training, facilitation, and more. We take pride in our ability to improve evidence-based practices in public safety agencies and gain organizational acceptance of those practices. We create realistic implementation plans, put them into practice, and evaluate their effectiveness to enhance the sustainability of policies, practices, and interventions. Find out more at www.crj.org/cji.