An Assessment of Earned Discharge Community Supervision Policies in Oregon and Missouri

Table of Contents

Many states have enacted comprehensive justice system reforms to reduce incarceration and community supervision in order to focus funding on people at higher risk of reoffending and invest in strategies to achieve better outcomes for people and communities. Many policy reforms have been spurred by significant growth in the population on community supervision and have focused on strategies to reduce the ballooning of community supervision. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, probation and parole populations nationwide grew 239 percent from 1980 to 2016 (Horowitz, Utada, and Fuhrmann 2018). Notably, community supervision populations peaked in 2007 and fell 11 percent between 2007 and 2016.1 Research on the impact of these policy changes has not kept pace with the rate at which they are enacted, leaving policymakers and practitioners with a knowledge gap concerning which reforms have worked and why.

In an effort to fill that gap, the Urban Institute and the Crime and Justice Institute assessed earned discharge policies in two states to understand their impact on people who are supervised, on supervision staff caseloads, and on outcomes including revocation and recidivism. Earned discharge refers to the reduction of a community supervision term for a person who is identified as eligible based on compliance with the conditions of their supervision and/or meets their case plan goals. It is intended to encourage people to meet the conditions of their supervision and/or to reward their progress on their case plan. Adopting earned discharge policies allows states to reduce supervision terms for people who are doing well, shrink caseloads, and focus resources on people at high risk of reoffending and those in their first year of supervision.

Research has shown that supervision is most effective when it focuses on people who are at higher risk of reoffending and that recidivism rates drop precipitously after the first year of supervision (Alper, Durose, and Markman 2018; Andrews and Bonta 2010). Some studies have indicated that incentives may promote changes in people’s behavior while on supervision,2 and that the potential for early discharge can be a strong motivator for people to comply with their supervision requirements (Wodahl, Garland, and Mowen 2017).

To reduce recidivism rates and make community supervision more effective, some states have awarded earned discharge from supervision to people who fulfill their supervision conditions. States have chosen different approaches to implement their earned discharge policies. For this assessment, we selected two states that approached the awarding of credits differently. Some states, including Missouri, have implemented a system that automatically awards credits for each month of compliance. In contrast, Oregon began with a similar credit system but later transitioned to a review of compliance at the midpoint of supervision to consider earned discharge. Guided by general parameters in Oregon statute and administrative rule, local supervision authorities have discretion over how they implement earned discharge policies and procedures. Urban and the Crime and Justice Institute analyzed implementation and outcomes of both states’ policies.

In addition to tailored questions designed for Oregon and Missouri, we explore three overarching questions that apply to both:

- How has earned discharge been implemented?

- How is this policy reform related to supervision populations and caseloads?

- Are outcomes different for people who complete supervision through earned discharge compared with those who do not?

Earned Discharge in Oregon

In 2012, the Oregon Commission on Public Safety studied the state’s prison population and community supervision practices as part of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative. It found that the state’s prison population had risen by roughly 50 percent since 2000 and was projected to continue to grow (Oregon Commission on Public Safety 2012). It also found that many positive, evidence-based community supervision practices were already in place, but that the state had few tools for incentivizing people to comply with supervision through opportunities to earn early discharge.

The commission’s study and recommendations led Oregon to pass H.B. 3194 in 2013, which included a set of reforms intended to address the projected prison population growth, improve community supervision practices, and reduce costs. Among those reforms was an earned discharge policy that was initially designed as an incentive (for eligible supervision cases) in the form of a 30-day reduction in supervision for every 30 days of compliance. About three-quarters of the entire population on supervision is eligible for the earned discharge policy and generally includes probation and local control post-prison cases that are at least one year in length.3 That policy was revised in 2015 to provide for a review for discharge at the midpoint of each eligible case’s term rather than calculating credits to determine when someone may be considered for discharge. At the time of the review, if conditions related to payment of fines have been met, the person has received no recent administrative sanctions, and they have been actively participating in the case plan, the case is discharged.

Using data provided by the Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC) and the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, we assessed the state’s implementation of earned discharge and its relation to supervision populations and outcomes. Key findings include the following:

- Earned discharge is underused in Oregon; while just under three-quarters of people’s supervision terms are eligible for earned discharge, it has accounted for less than 10 percent of closures each year since the reform.

- The state implemented earned discharge by giving counties a large amount of discretion in how to award earned discharge. Counties vary widely in their use of earned discharge due to these differences.

- People ending supervision through earned discharge serve less of their total sentences than people receiving early terminations or ordinary discharges.4 Despite being underused, through 2019, earned discharge saved more than 61,000 months of supervision time.

- Earned discharge cases have the lowest overall three-year reconviction rates among all discharge types. Accounting for differences in the types of discharge groups and only comparing similar cases, those who receive earned discharge have a lower overall three-year reconviction rate (13 versus 18 percent) when misdemeanors and felonies are included. However, when only felonies are included, earned discharge closures have a statistically significant but not meaningfully higher recidivism rate, as the rate remains very low (6 versus 4 percent).

Background

Oregon passed H.B. 3194 to address prison growth, improve community supervision practices, and reduce costs. The legislation included provisions to invest savings in local strategies to reduce recidivism, create an earned discharge policy, increase community-based services and supports, offer presumptive probation for certain offenses, and allow probation or shorter sentences for some drug offenses.

Upon passage of H.B. 3194, the ODOC began developing its administrative rules for the earned discharge program, which is designed for people on probation or local control post-prison supervision for a felony or designated drug-related misdemeanor. People on supervision may have cases on multiple types of supervision at the same time. Cases supervised as part of parole or post-prison under the authority of the Oregon Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision are not eligible for earned discharge. However, cases on probation and local control post-prison supervision are eligible. About three-quarters of people’s supervision terms, across the entire supervision population, in 2019 were eligible to be closed to earned discharge. No matter the authority (the Oregon Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision or the courts), supervision is carried out by local supervision authorities, led by a local community corrections director or sheriff. The ODOC partners with and provides oversight for 34 Oregon counties for community supervision. Moreover, the ODOC fully manages community supervision in 2 counties. As part of its oversight, it provides guidance on policy development and implementation, provides technical assistance and evaluation support, develops statewide budgets and distributes general fund dollars targeted for county community corrections programs, reviews and audits local systems, and enforces policies (when necessary).

Oregon’s earned discharge program was originally designed to provide an incentive of 30 days off a supervision sentence for every 30 days of compliance. The supervising agencies found it difficult and cumbersome to calculate the credits, so in 2015, the policy was legislatively revised to provide for a review for discharge at the midpoint of every eligible case’s term. The ODOC tracks people’s supervision terms and notifies the relevant county when someone is nearing the midpoint of their term and is eligible for consideration for earned discharge. Eligibility remained the same: cases still had to serve at least 50 percent of the period of supervision, the time on supervision could not be less than six months, and people had to be on probation and local control post-prison supervision for a felony or designated drug-related misdemeanor. To be eligible, people must also have fully paid restitution and compensatory fines, they must not have been administratively sanctioned (not including interventions) or found in violation by the court in the six months before their review, and they must be actively participating in their supervision case plan.

The definition of compliance with case plan conditions, and therefore whether people can receive earned discharge, is discretionary and varies by county. The ODOC has encouraged counties to use internal policies to ensure consistency among offices within each county. Counties’ policies can define compliance with treatment conditions as being actively engaged in treatment or as having completed it, and policies can prescribe different circumstances in which sanctions can be used for people on supervision. This means that counties may respond to the same behavior differently, and therefore that they may approve earned discharge differently. In addition, some prosecutors and judges have required that cases be brought back before them before discharge. Although this is not legally required, some counties have reached agreements with prosecutors and judges to do so.

Lastly, Oregon uses an incentive funding model for local community corrections and maintained this model in crafting the earned discharge policy. Local supervision authorities are given state funding for people they supervise, except for nondesignated drug-related misdemeanor offenses. Because earned discharge would reduce the number of people supervised by local agencies, H.B. 3194 requires that these cases still be funded to their latest possible supervision end date regardless of whether they are discharged early so as not to deprive local agencies of funding. Although the state does not spend less in total for the people who are discharged from supervision early, local community corrections agencies can spend the money not spent on supervising people earning discharge on evidence-based practices and reinvestment to improve system outcomes.

Our analysis, which uses data from the ODOC, includes data on all admissions to supervision (i.e., probation, parole/post-prison supervision, and local control post-prison supervision) from January 2009 through December 2019. The data include information on offense type, authority type, risk level, supervision start and release dates, sanctions and incentives, conditions, and demographic characteristics. The analysis also uses recidivism data from the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission. In addition, we visited community corrections leaders and staff in two counties and conducted virtual interviews with those in four others. The virtual interviews, like the site visits, included various agency representatives, including directors, administrators, supervisors, and officers. See box 1 for key terms in Oregon community supervision, and see the technical appendix for more information about the data sources and methodology.

We examined the implementation of the earned discharge program and its impact on supervision populations, comparing outcomes for people who received earned discharge with outcomes for those who did not. Notably, the findings and recommendations from this project were shared in real time with Oregon stakeholders. As a result, the state made several adjustments in line with the recommendations in this brief to the earned discharge policy through House Bill 2172 in 2021. These new changes5 are not reflected in the analysis presented in this brief. Our key research questions for Oregon are as follows:

- To what extent have agencies in Oregon implemented earned discharge for people on probation and local control post-prison supervision?

- What proportion of people meeting statutory requirements for eligibility are receiving earned discharge? Do differences exist based on race, ethnicity, gender, county, supervision type, offense type, or risk level?

- How has the length of supervision changed for people ending supervision through earned discharge, and does that differ by county?

- Do recidivism outcomes differ for people who received earned discharge compared with a matched group who were eligible and successfully completed supervision but not through earned discharge?

Box 1

Key Terms in Oregon Community Supervision

Bench probation is unsupervised probation, meaning the person on probation has conditions but does not meet with a supervision officer. In the data used for this report, bench probation indicates that a case has been transferred to bench probation from formal supervision, typically because of a person’s positive performance while on formal supervision.

Board control post-prison supervision is supervision of a person who has served more than 12 months in custody in an ODOC facility, whose conditions and supervision length are set by the Oregon Board of Parole, and who is supervised by local community corrections offices.

Closure refers to successful or unsuccessful termination from a supervision term that includes early termination, earned discharge, ordinary discharge, other discharge, or revocation.

Early termination is a kind of successful closure prior to the end of a person’s probation sentence. To be considered for early termination, a person must have completed at least one year of supervision; must not have been convicted of a violent crime, a sex offense, or terrorism; and must not have committed repeated drug offenses. Compliance with supervision conditions, progress toward their reentry goals, and other factors are also considered.

Earned discharge refers to successful closure resulting from earned discharge.

Eligible supervision terms are terms that have an eligible controlling offense (owing to supervision type and length) to be considered for earned discharge. A person is eligible for review if the supervising authority is probation or local control post-prison supervision and their sentence is at least one year, because Oregon statute indicates that supervision periods cannot be shortened to less than six months. Note that some figures in this report show eligibility before 2013; these are supervision terms that would have been eligible had the earned discharge policy been in place.

Ineligible supervision terms are those that have an ineligible supervising authority (i.e., board control post-prison supervision) or do not have a sentence of at least one year.

Local control post-prison supervision is a kind of supervision through which a person serves a term under the jurisdiction of a local supervisory authority after serving a local control custody sentence of 12 months or less.

Ordinary discharge refers to closure that is a successful completion owing to expiration of a supervision term.

Other discharge refers to closure resulting from dismissal, appeal, or rejected/withdrawn interstate compact case.

Revocation refers to closure ending in incarceration of a person on supervision.

Supervision sentence length is the anticipated end date of a supervision term minus the start date.

Successful completion refers to positive supervision closure, including terms ending in earned discharge, early termination, release to bench probation, or ordinary discharge.

Supervision term is a period of continuous supervision that can include multiple sentences with different sentencing dates.

Unsuccessful completion means a supervision term ending in revocation.

Source: Oregon Department of Corrections – Community Corrections Division.

Findings on Earned Discharge in Oregon

Earned Discharge is Used in Oregon, Though Infrequently

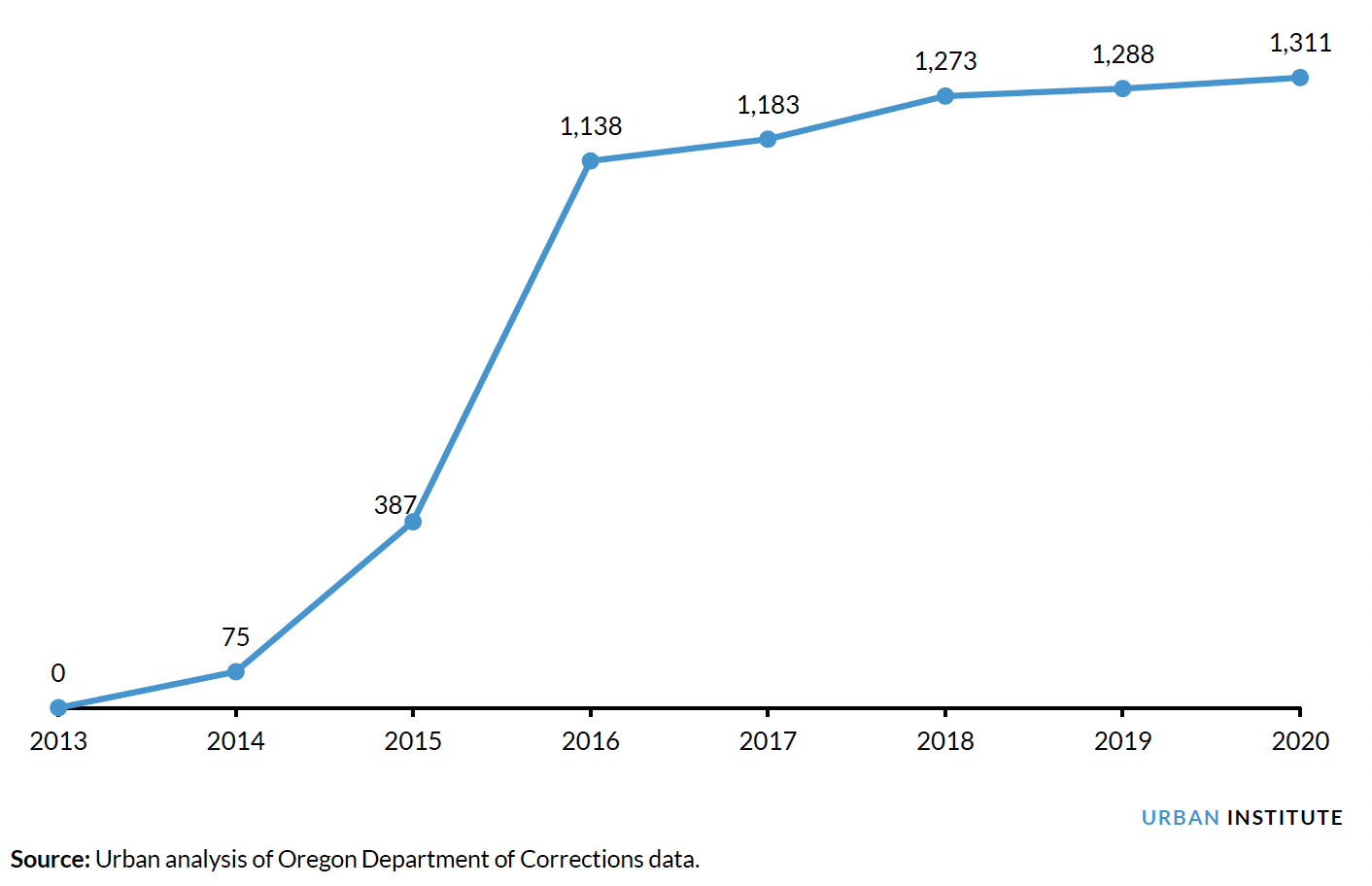

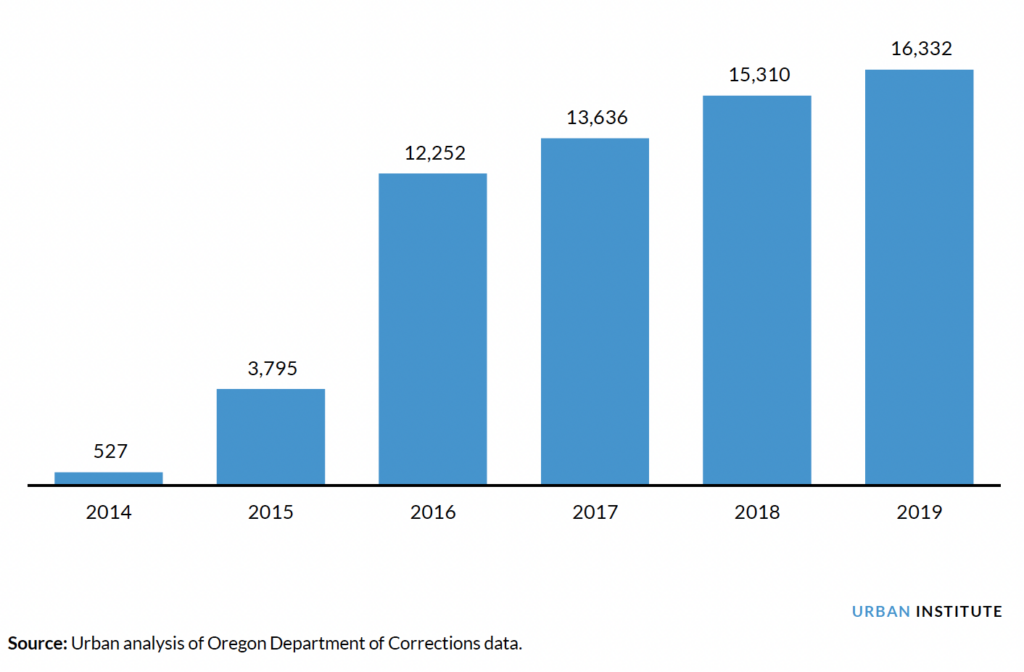

In 2019, 20,539 supervision terms for people in Oregon ended. Though the number has been growing in recent years, in 2019, fewer than 1,500 closures closed to earned discharge. Figure 1 shows people’s supervision terms that have closed because of earned discharge since the state implemented it.

Figure 1: Number of Supervision Terms Closed per Year in Oregon Because of Earned Discharge

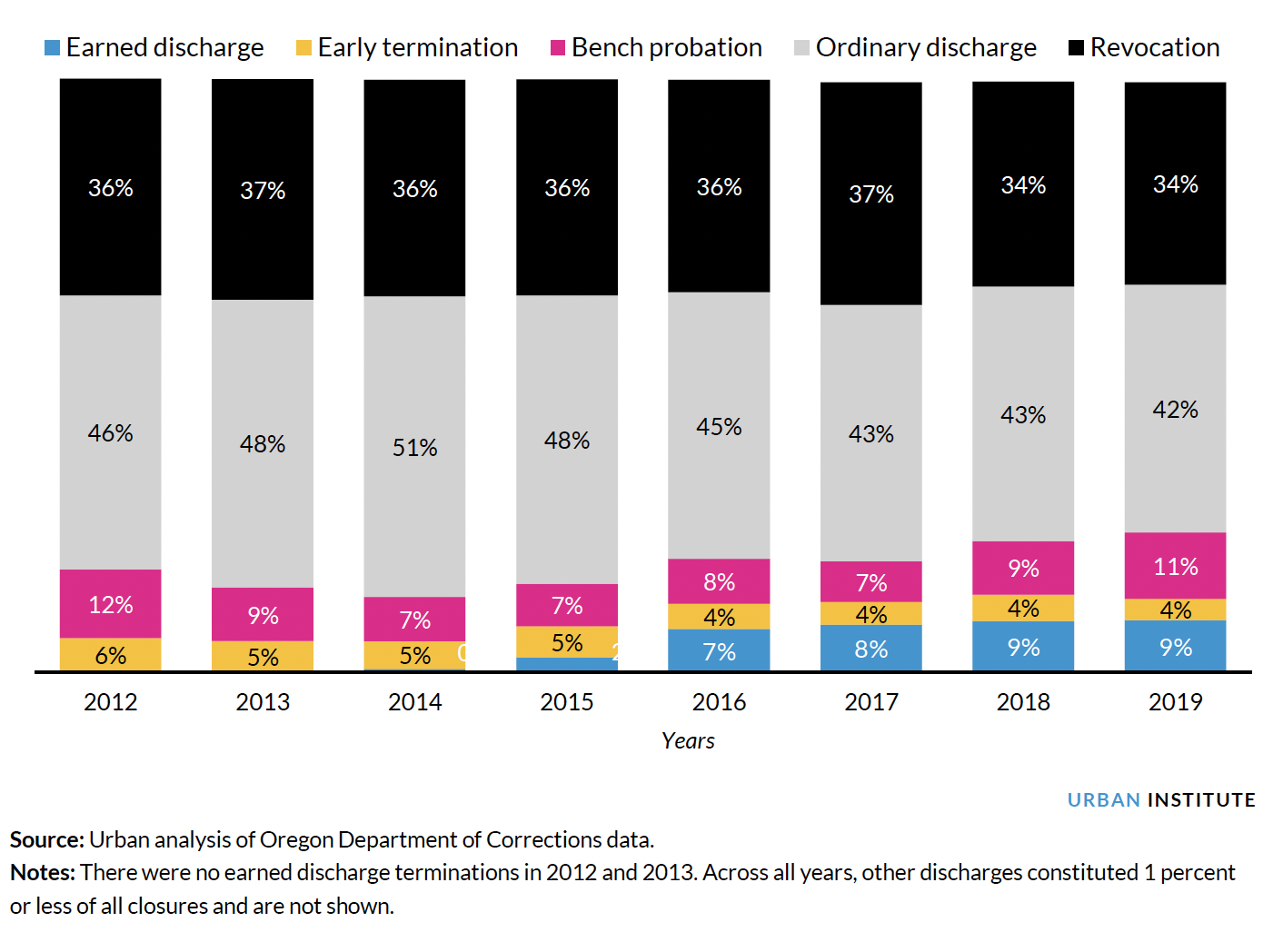

In 2019, 70 percent of people’s supervision terms, or 14,398 closures, were eligible for earned discharge. Nine percent of those terms that were eligible in 2019 received earned discharge, whereas 42 percent received ordinary discharge (the most common closures that year; figure 2). Ordinary discharges are supervision terms that closed owing to expiration of supervision terms. In 2019, 34 percent of eligible terms closed through revocation, 11 percent closed to bench probation, 4 percent closed because of early termination, and 1 percent closed through kinds of discharge other than those shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Percentage of Closures Eligible for Earned Discharge Ending by Closure Type by Year in Oregon

Among only those people who successfully completed supervision, in 2019, 64 percent of successful eligible completions closed to ordinary discharge, 17 percent to bench probation, 13 percent to earned discharge, and 6 percent to early termination.

Supervision staff report that the most common reasons people do not receive earned discharge include failure to pay restitution, failure to complete treatment or community service, and violations. Even in counties that are motivated to discharge people early, many people considered for earned discharge are not awarded it due to behavioral reasons, such as sanctions related to relapses in drug use.

Despite the relatively low use of earned discharge, community supervision staff we interviewed generally consider it beneficial because it can be an effective incentive for people on supervision. Even people who do not meet the conditions by the midpoint of their supervision terms are often motivated to meet those conditions before subsequent reviews. Some interviewees noted that earned discharge has helped reduce their caseloads, and many prefer earned discharge over other methods of managing caseloads, such as early termination.

How a policy or program is initially implemented and how it is subsequently monitored and measured can impact rates of its use. In this case, supervision agency leaders reported that the ODOC provided little training on how to implement earned discharge. In addition, county staff reported having received minimal support or oversight from the ODOC to encourage their use of earned discharge. The ODOC sends counties a monthly list via email of people who are approaching the halfway mark of supervision, but counties must establish their own systems for ensuring that eligible people are considered for earned discharge. Furthermore, that monthly list excludes people who were initially denied earned discharge but are eligible for a subsequent review, so counties are not reminded to review people more than once. Some counties have established their own systems to track people who could be considered at subsequent reviews; others have not. Many of the staff we interviewed want clearer and more consistent statewide definitions of earned discharge eligibility, which they believe would increase equity, reduce confusion, and expedite decisionmaking. Lastly, few data are collected and shared on earned discharge besides rates of use, so counties lack a clear sense of how it impacts their offices and whether it is working as intended.

Earned Discharge Use Varies by County, Supervision Type, and Demographics

Broken down by supervision type, gender, and race, the share of the eligible population that successfully completes and ends supervision on earned discharge varies. People on probation are less likely to be eligible for earned discharge than people on local control post-prison supervision (84 versus 100 percent), but people on probation who are eligible are roughly as likely to successfully complete as eligible people on local control post-prison supervision (65 versus 64 percent); and among those who are eligible and successfully complete, people on probation are more likely to actually exit supervision on earned discharge (14 versus 8 percent).

Moreover, among eligible people on any type of supervision, women are more likely to be eligible than men (77 versus 68 percent), and among those who are eligible, women are more likely to successfully complete (70 versus 63 percent). However, among eligible people who successfully complete, men and women are equally likely to close on earned discharge.

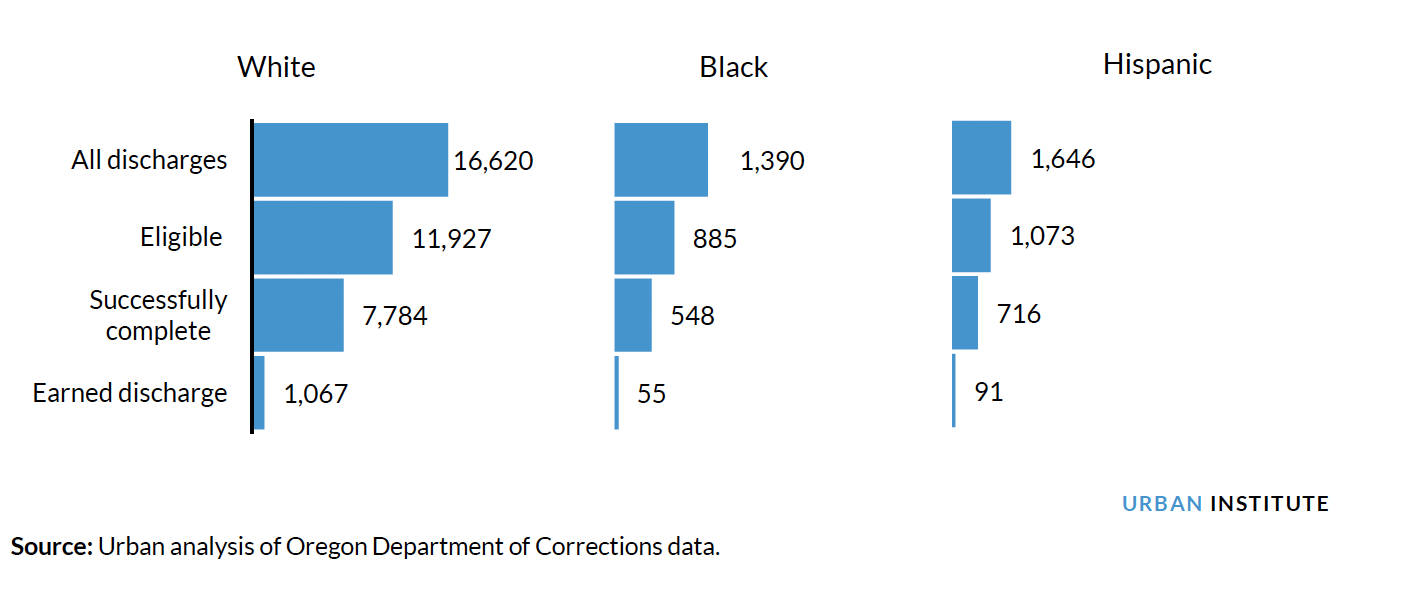

As figure 3 shows, among all discharges, white people are more likely than Black and Hispanic people to be eligible, to successfully complete within the eligible group, and to close to earned discharge if an eligible completer.

Figure 3: Shares of White, Black, and Hispanic People in Oregon Receiving Discharges Who Were Eligible, Successfully Completed, and Received Earned Discharge in 2019

Most terms that close to earned discharge have a primary offense related to drugs, property, or “other” (which includes offenses such as driving under the influence, felony possession of a firearm, and unlawful weapon use). In 2019, 75 percent of earned discharge closures fell into those categories, compared with 81 percent of eligible closures.

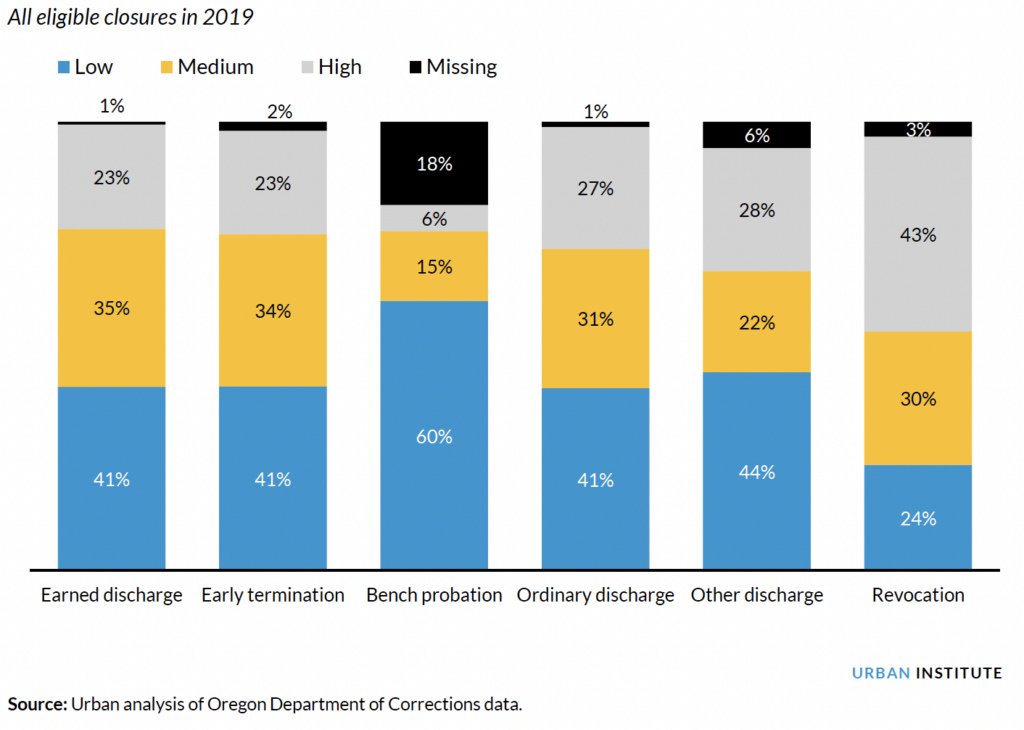

Among eligible people, people who close to earned discharge and early termination have similar risk profiles (figure 4). Among earned discharge closures in 2019, 41 percent were scored as low risk, 35 percent as medium risk, and 23 percent as high risk. That year, among people closing to early termination, 41 percent were scored as low risk, 34 percent as medium risk, and 23 percent as high risk.

Figure 4: Risk Levels among People under Supervision in Oregon by Supervision Closure Type

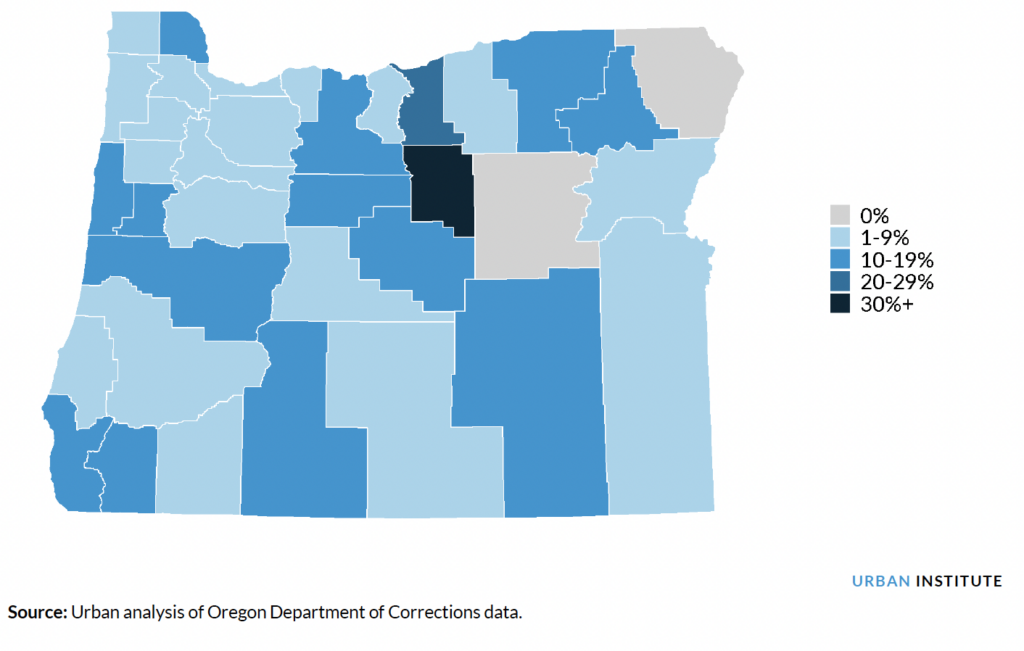

As figure 5 shows, the share of people who close to earned discharge varies by county of conviction, ranging from a low of 0 percent to a high of 33 percent of all closures ending with earned discharge.

Figure 5: Percentage of Eligible Closures Ending in Earned Discharge in Oregon by County in 2019

Earned discharge policies and practices (and thus outcomes) vary by county because of structural and cultural reasons. Per state administrative rule, one of the criteria for earned discharge is compliance with the conditions of supervision and of one’s case plan. A person is expected to be actively participating in their supervision case plan,6 a clause that is open to interpretation by supervising authorities (for instance, does someone on supervision need only to be making progress, or must they complete their case plan before being considered?).

Moreover, not all counties provide subsequent reviews to people denied earned discharge at the halfway point of supervision. Regarding such reviews, administrative rule states, “The supervising officer may conduct a subsequent earned discharge review at any point thereafter.”7 Some county community supervision offices have implemented oversight systems to prompt officers to do subsequent reviews, whereas others provide no such oversight. Staff from offices that have implemented oversight systems note that use of earned discharge has increased since they did so. Also, some offices have simplified and streamlined the earned discharge review process, whereas staff in other counties consider their processes cumbersome.

A third reason for geographic variation is how counties have negotiated their earned discharge policies with local stakeholders differently. Although state law permits county community supervision offices to discharge people from supervision via earned discharge without court authorization, some seek informal approval from the court as a courtesy and/or honor judges’ designations of certain cases as ineligible for earned discharge on the court order.

Finally, the community supervision culture in different counties and offices may be impacting the use of earned discharge. For example, some staff we interviewed consider earned discharge too lenient.

Shortened Supervision Terms Resulting from Earned Discharge Have Saved Thousands of Months of Supervision Time

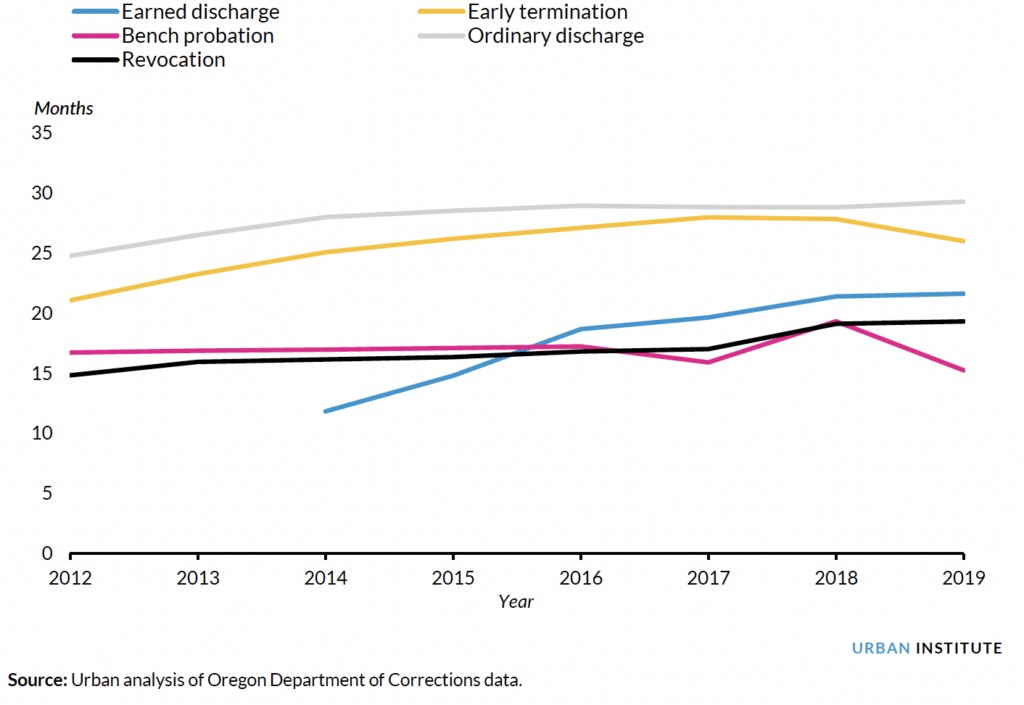

People who are eligible and ineligible for earned discharge are receiving supervision sentences of about the same duration. In 2019, people who were eligible had an average sentence of roughly 26 months, compared with 29 months for people who were ineligible. The time people were actually spending on supervision increased slightly between 2013 and 2019. In 2013, terms ending successfully served on average 25.7 months; by 2019, that average was 26.6 months. Figure 6 shows that as of 2019, among eligible completions, average length of stay was shortest for terms releasing to bench probation, but terms closing to earned discharge were also spending several months less on average than terms closing to early termination and ordinary discharge.

Figure 6: Average Number of Months People Spent on Supervision among All Eligible Completions by Completion Type, 2012 to 2019

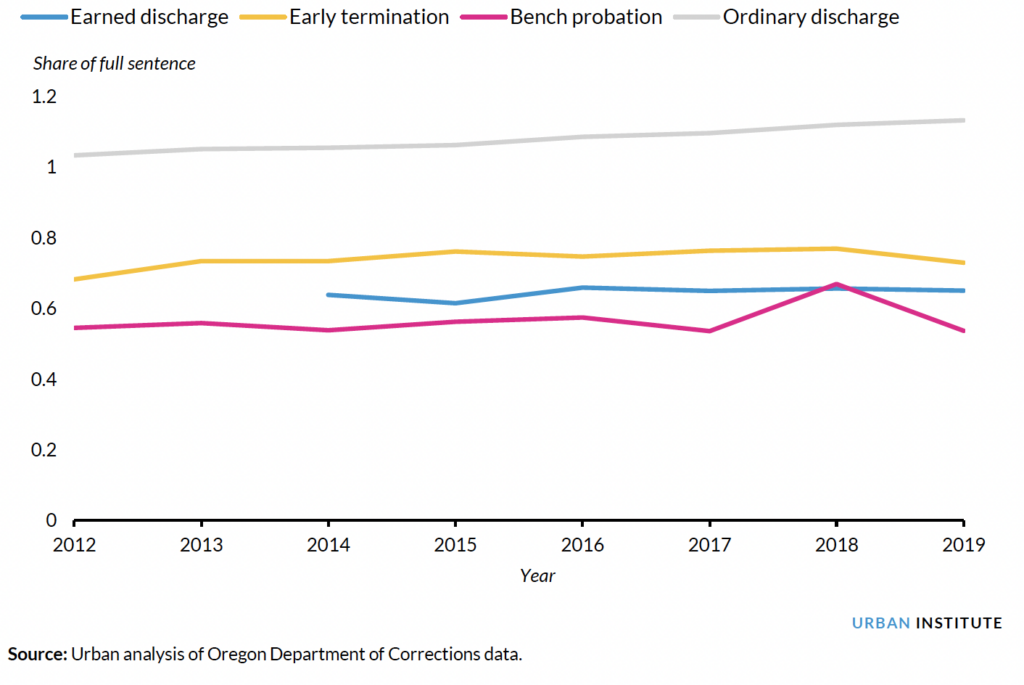

Moreover, people ending supervision with earned discharge serve less of their sentence on average than people ending on early termination and ordinary discharges. As figure 7 shows, terms ending in earned discharge serve roughly two-thirds of their sentence on average.

Figure 7: Share of Full Sentence Being Served among All Eligible Completions by Closure Type, 2012 to 2019

Earned discharge closures reduced the average supervision term by 13 months in 2019. Across Oregon that year, this aggregated to 16,332 total months “saved” from supervision terms owing to the earned discharge policy (figure 8).

Figure 8: Total Months Saved per Year Off of Supervision Sentences Because of Earned Discharge, 2014 to 2019

People Receiving Earned Discharges Have Similar Recidivism Rates as People Receiving Other Successful Completions

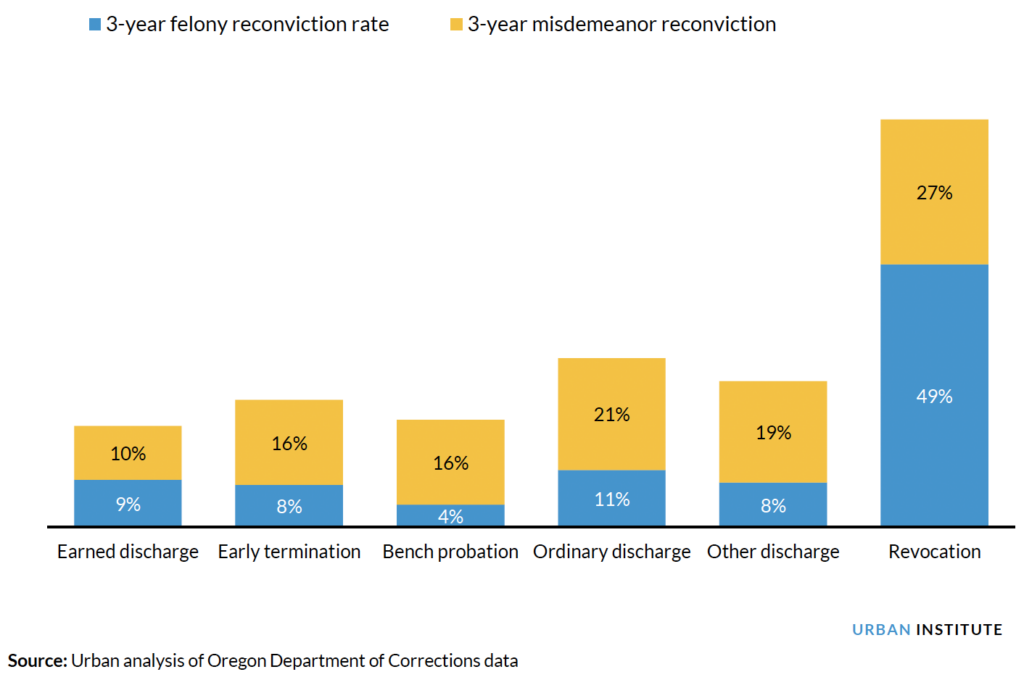

Those exiting supervision through earned discharge are doing so having served less time than those closing their terms successfully through other methods. Research indicates that the benefits of supervision decline over time (Alper, Durose, and Markman 2018; Andrews and Bonta 2010), and this assessment explored whether the reduction in supervision time paired with the incentive of earning discharge was associated with any differences in recidivism rates compared with cases that did not receive earned discharge. For this analysis, we define recidivism as reconviction of a felony or misdemeanor within one, two, and three years of starting supervision.8 As figure 9 shows, after earned discharge was implemented, people who were eligible for earned discharge and who closed their supervision term on earned discharge had a lower total reconviction rate (19 percent) than people ending their supervision on any other closure type.

Figure 9: Three-Year Felony and Misdemeanor Reconviction Rates among the Eligible Population Admitted to Community Supervision between August 2013 and December 2017, by Closure Type

Because particular cases within each discharge type can be very different, we also ran an analysis to make the groups more comparable to better understand the recidivism-rate differences associated specifically with receiving earned discharge.9 We compared people who received earned discharge (the treatment group) with a similar group of people who were eligible for earned discharge but successfully closed to a different discharge type (the comparison group). The treatment and comparison groups comprised people on probation or local control post-prison supervision who started supervision after January 2014, successfully closed, and had a controlling offense that was eligible for earned discharge. The two groups were matched on relevant characteristics through propensity-score matching. We examined recidivism as new convictions within three years of starting supervision.

After matching and controlling for relevant factors, we found that felony reconviction rates were slightly higher for people exiting supervision through earned discharge than for people exiting through other discharge types. The treatment group had a three-year felony reconviction rate of 6 percent, whereas the control group had a three-year felony reconviction rate of 4 percent. Regarding total three-year reconviction rates (i.e., felonies and misdemeanors), the group that ended supervision on earned discharge had a reconviction rate that was statistically significantly lower than the matched group of people who closed through other discharge types. Earned discharges had an overall three-year reconviction rate of 13 percent, compared with 18 percent in the comparison group.

Earned Discharge in Missouri

In 2011, the Missouri Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections found that prison admissions had risen by more than 100 percent in the prior two decades, and that admissions were being driven by high numbers of revocations from community supervision, including probation and parole.10

Missouri H. B. 1525, which contained the recommendations of the Missouri Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections and which created an earned compliance credit (ECC) program for people on probation and parole, was signed into law in 2012. Policymakers and practitioners designed the program to incentivize people on community supervision to comply with their probation or parole conditions by allowing them to earn 30 days off their supervision terms for every month of compliance. Using data from the Missouri Department of Corrections (MDOC), we examined the implementation of the ECC policy and its impact on supervision populations and outcomes for people who were eligible for ECCs and people who received ECC discharge, compared with people who were ineligible or were eligible and did not receive ECC discharge.

Key findings indicate that the following occurred between ECC program implementation in September 2012 and December 2018 (the end of our analysis period):

- The number of people under supervision declined substantially.

- A majority of people discharged successfully from supervision received ECC discharge.

- Rates of ECC discharges differed by people’s demographic characteristics, county, and supervision type.

- The average duration of supervision sentences and time spent under supervision decreased.

- People who were eligible for ECCs and who successfully completed supervision had fewer violations than comparable people who were revoked from supervision.

- Recidivism rates were low among people who successfully completed supervision, regardless of whether they received ECCs.

- Missouri experienced challenges implementing the ECC program—due to changing eligibility criteria and different interpretations in different geographic jurisdictions—and the MDOC responded by convening a team to assist.

Background

Between 1990 and 2011, Missouri’s prison population more than doubled to more than 30,000 people. Moreover, the number of people under supervision rose from 62,759 in 2001 to 73,904 in 2010, and from 1990 to 2009, corrections spending increased almost 250 percent. In 2010, 71 percent of admissions to prison were for revocations of supervision, 31 percent were for probation revocations, and 40 percent were for parole revocations. Of all admissions to prison in 2010, 43 percent were for technical violations of probation or parole. From 2005 to 2010, most revocations (roughly 80 percent) occurred before the end of people’s second year of supervision, and the average probation term was 4.5 years, meaning most people on probation were being supervised long after their risk of revocation lessened (Missouri Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections 2011).

In 2013, Missouri passed H. B. 1525 as part of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative. State leaders sought ways to cost-effectively improve supervision across the state. The bill created earned compliance credits for people on probation and parole, awarding eligible people 30 days off their supervision terms for every month of compliance with supervision conditions. In Missouri’s case, compliance means the absence of an initial violation report submitted by a probation or parole officer during a calendar month, or the absence of a motion to revoke to suspend supervision filed by a prosecutor. The MDOC Division of Probation and Parole oversees the supervision of everyone on felony probation and parole. Conditions for supervision are established by judges for people on felony probation and by the Missouri Board of Probation and Parole for people on parole.

Most people on felony supervision in Missouri are eligible to earn compliance credits, which are available to people convicted of a felony drug offense or a Class D or E felony.11 For certain otherwise eligible offenses, the sentencing court may make a finding that a person is ineligible for credits. Only when people have completed two years under supervision and paid restitution can they be discharged via earned credits. Eligible people can accrue credits after the first full calendar month of supervision. Anyone who began a term of probation or parole before September 1, 2012, could begin accruing credits on October 1, 2012.

Notably, some parameters of the ECC policy have been modified since H.B. 1525 was passed. In 2018, Missouri clarified circumstances in which credits do not accrue during a given month. Currently, credits do not accrue for someone if the outcome of a hearing is pending during any month in which a violation report (which can include a report of absconder status) has been submitted, if they are in custody, or if a motion to revoke or to suspend has been filed. Further, credits are rescinded if the court or board revokes probation or parole, or if the court finds the person ineligible to earn credits because of the nature and circumstances of the violation. If the court places the person in a 120-day program or postconviction drug treatment program, credits do not accrue while they are completing the program.12

Using data from the MDOC, our analysis includes data about people 18 years or older under supervision (probation or parole) for a felony offense from January 2008 through December 2018. The data include information on offense type, supervision type, classifications, sentence length, supervision start and release dates, criminal history, risk and need scores, violations, recidivism events, and demographic factors. In addition, Urban and the Crime and Justice Institute interviewed various people—including MDOC administrators, supervisors, and officers, as well as a prosecuting attorney and a judge—to better understand ECC procedures and practices. See box 2 for key terms in Missouri community supervision, and see the technical appendix for more information about the data sources and methodology.

We examined the implementation of ECCs, changes to the supervision population, and outcomes for people who received ECCs compared with those who did not. Our key research questions for Missouri are as follows:

- How has the introduction of ECCs impacted the number of people under supervision?

- What proportion of people eligible to earn credits received ECC discharge, and are there any differences based on supervision type, gender, race, district office, or risk level?

- How has the length of supervision changed for people eligible to earn ECCs?

- How does compliance with conditions interact with earning credits?

- Is there a difference in the rate of reconviction for people who were eligible for ECCs compared with a matched group who could have been eligible but finished supervision before the ECC policy was implemented?

- How have ECCs been implemented at both the agency level (in terms of policy change) and at the staff level in operationalizing the policy changes on the ground?

Box 2

Key Terms in Missouri Community Supervision

Closure means termination from an MDOC supervision term.

ECC discharge refers to a successful completion resulting from earned compliance credit status.

ECC-eligible terms are supervision terms of at least two years that have an eligible offense. Some figures in this section show ECC-eligible terms before 2012; these are supervision terms that would have been eligible had the ECC policy been in place.

Ineligible supervision terms are those that do not have an eligible offense or do not meet the two-year time requirements.

Ordinary discharge refers to successful completion that does not result from ECCs.

Revocation refers to closure ending in incarceration of someone on a supervision term. Revocations include a small number of terms closing on abscond status but do not include interstate transfers or death.

Successful completion (i.e., ECC discharge or ordinary discharge) refers to closure that does not include incarceration, abscond status, interstate transfer, or death.

Supervision sentence length refers to the anticipated end date of a supervision term minus the beginning date of the supervision term.

Supervision term refers to a period of continuous MDOC supervision that can include multiple sentences with different sentencing dates.

Findings

The Number of People under Supervision Declined after H.B. 1525

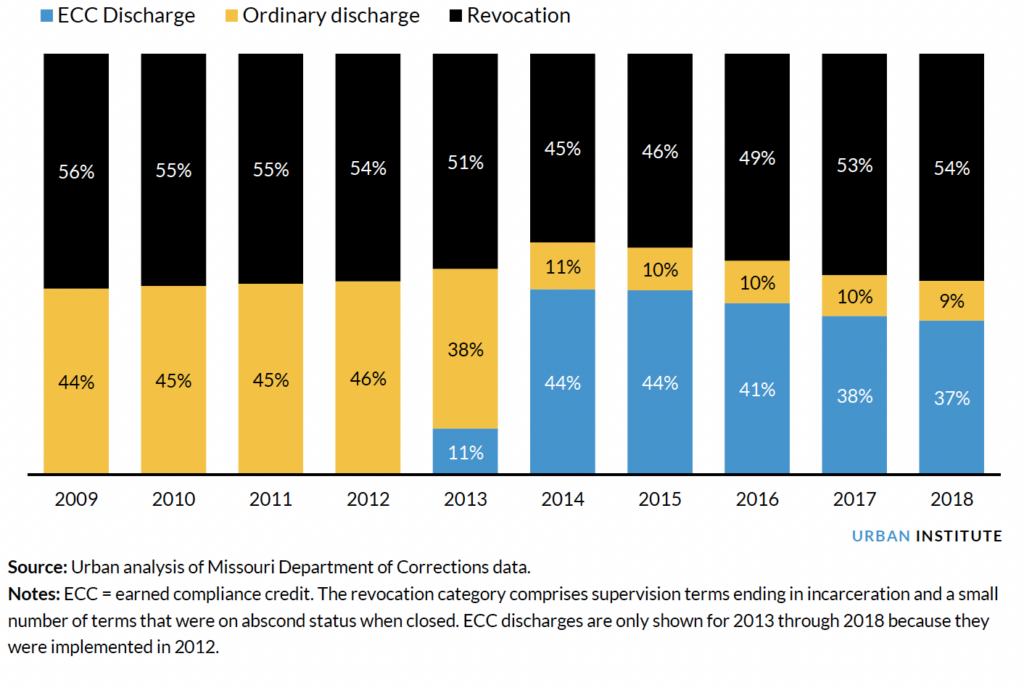

In 2012, when H.B. 1525 was signed into law, Missouri had 77,331 people under supervision through probation and parole. By 2018, that number had declined 23 percent to 59,326. That decline was driven by supervision closures, which increased 17 percent in the first year after the legislation (from 32,307 in 2012 to 37,888 in 2013). In 2014, there were 37,515 closures. Although supervision closures declined after those initial two years, they remain higher than prereform.13

The sharp rise in supervision closures in the two years postreform was a function of ECCs applying not just to people starting supervision, but also to those who began a term of probation, parole, or conditional release before September 1, 2012. Many people who had served a majority of their supervision term before the reform became eligible to earn credits and could shorten their remaining terms and discharge early because of ECCs.

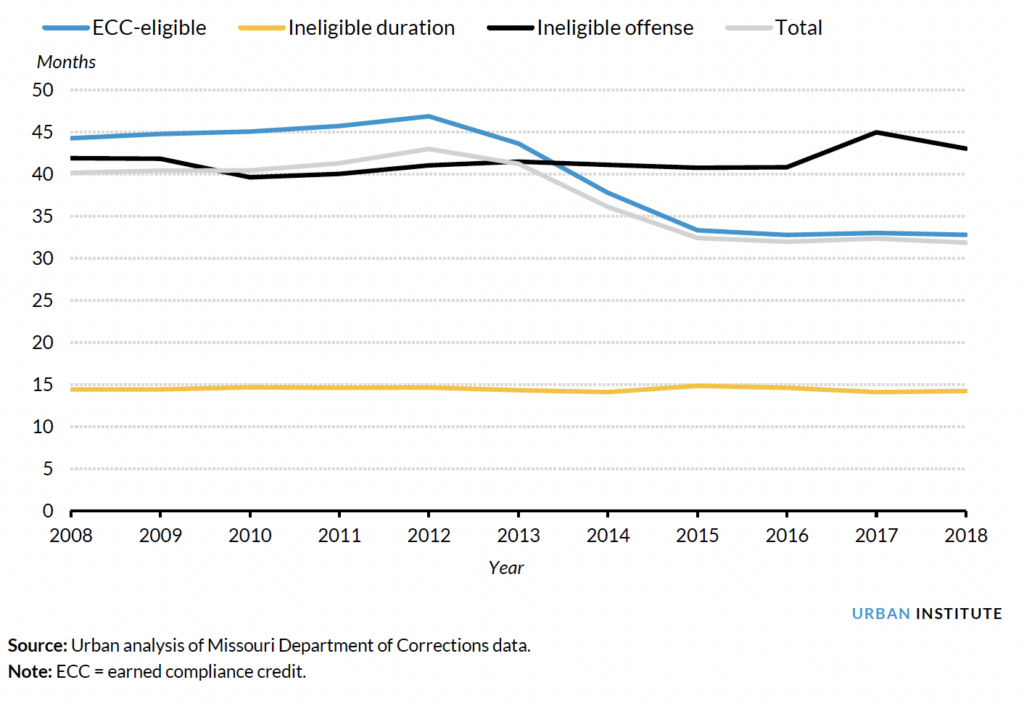

In addition to closures, changes in average time spent under supervision have reduced Missouri’s supervised population. As figure 10 shows, average time spent under supervision for people who were eligible for ECCs and who successfully completed declined 30 percent, from 47 months in 2012 to 33 months in 2018.

Figure 10: Average Time Spent on Supervision for All Successful Completions by Eligibility and Year of Closure (in Months), 2008 to 2018

The Majority of Successful Supervision Discharges Are through Earned Compliance Credits

In Missouri, a person under supervision is ECC eligible if they have an eligible offense (i.e., a felony drug offense or, as of 2017, a Class D or E felony) and have at least two years to serve under supervision. Among everyone with supervision terms from 2012 through 2019, 25 percent of people on parole were ineligible because of the length of their supervision term, and 15 percent of people on parole were ineligible because of their offense. A much smaller proportion of people on probation during this period were ineligible to earn credits: only 1 percent of people on probation were ineligible because of the length of their supervision term, and 6 percent were ineligible because of their offense. Eighty-five percent of all people eligible to earn credits during this period were convicted of drug or nonviolent offenses.

In the year after the compliance credits were implemented, just over one-half of ECC-eligible people (16,851 out of 31,934) successfully completed supervision. As figure 11 shows, the proportion of ECC-eligible people who successfully completed supervision dropped each year since 2013 to 46 percent in 2018 (11,384 of 27,601 closures).

Figure 11: Yearly ECC-Eligible Closures by Type of Closure, 2009 to 2018

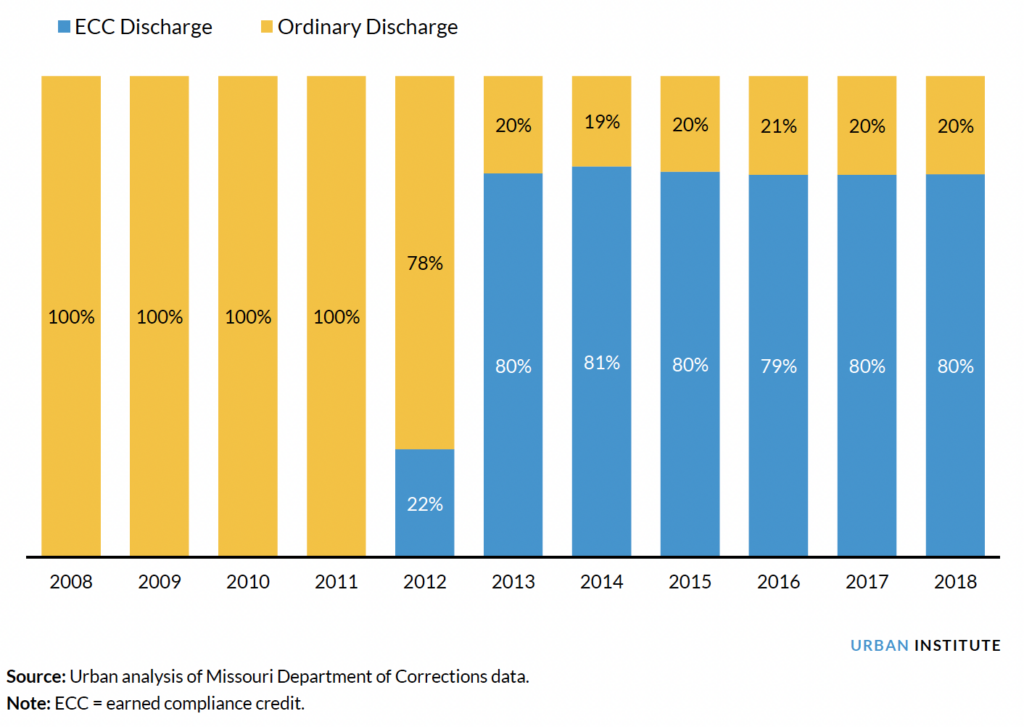

Figure 12 shows that when looking at only those who successfully finished supervision, 8 in 10 received ECC discharges rather than ordinary discharges each year from 2013 through 2018.

Figure 12: Yearly ECC-Eligible Successful Completions by Type of Discharge, 2008 to 2018

Differences in ECC Discharges Exist Based on Demographic Characteristics, County, and Supervision Type

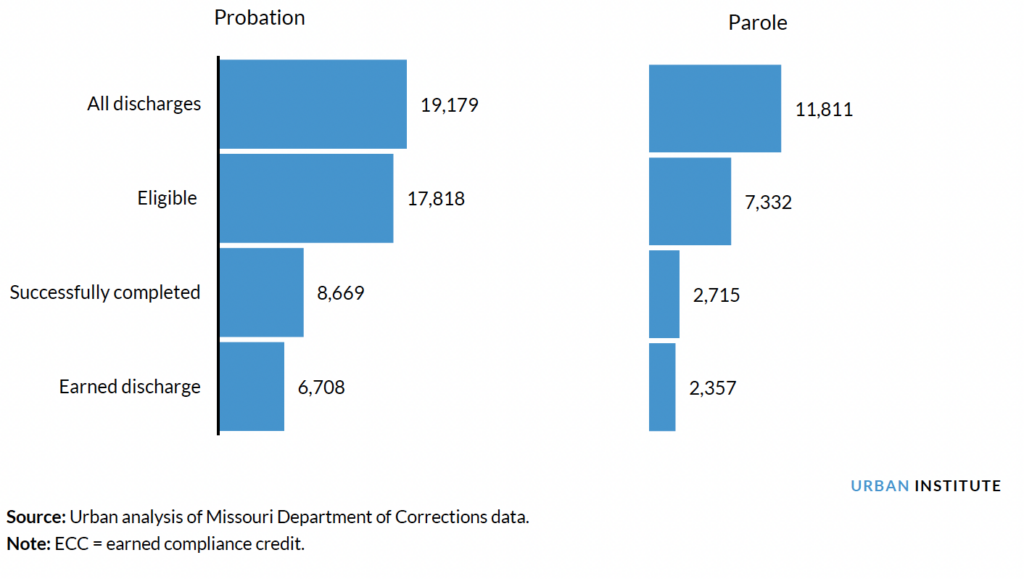

There is variation in ECC discharges among people with different demographic, geographic, and supervision-type characteristics. A greater proportion of people on probation (93 percent) were eligible to earn compliance credits than people on parole (62 percent) (figure 13). Although people under parole supervision who were eligible to earn credits were less likely to complete supervision successfully (37 percent) than those on probation (49 percent), people on parole who did successfully complete and were eligible for ECCs were more likely to discharge via ECCs (87 percent) than people on probation (77 percent).

Figure 15: Number of People Discharged from Probation and Parole Who Were ECC Eligible, Successfully Completed, and Received ECC Discharges in Missouri in 2018

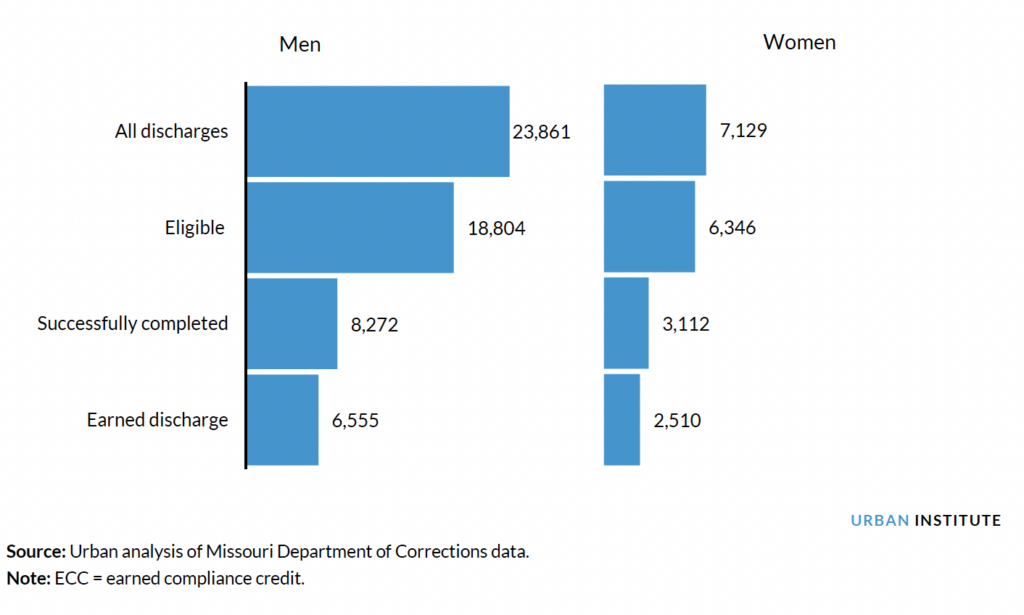

A greater proportion of women than men were eligible to earn compliance credits (89 percent versus 79 percent) because they were more likely to have an eligible offense and meet the two-year minimum sentence requirement. Women who were eligible for ECCs were more likely than eligible men to successfully complete supervision in general (45 percent versus 40 percent), and women who successfully completed and were ECC eligible were more likely to discharge through ECCs (81 percent, versus 79 percent of men) (figure 14).

Figure 14: Number of Men and Women Discharged from Probation and Parole Who Were ECC Eligible, Successfully Completed, and Received ECC Discharges in Missouri in 2018

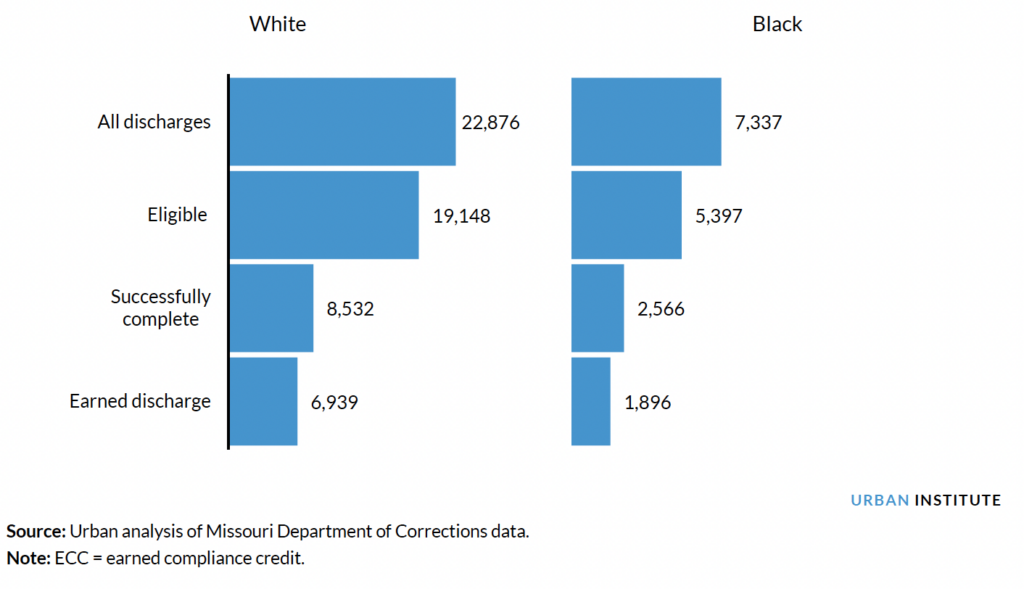

A smaller proportion of Black people (74 percent) than white people (84 percent) who ended supervision in 2018 were eligible for ECCs because they were less likely to have an eligible offense and less likely to meet the two-year minimum sentence requirement (figure 15). Although Black people were less likely to be ECC eligible, those who were eligible were slightly more likely than eligible white people to successfully complete supervision (43 percent versus 41 percent). Among ECC-eligible successful completers, white people were more likely than Black people to discharge under the ECC policy (81 percent versus 74 percent).

Figure 15: Number of White and Black People Discharged from Probation and Parole Who Were ECC Eligible, Successfully Completed, and Received ECC Discharges in 2018

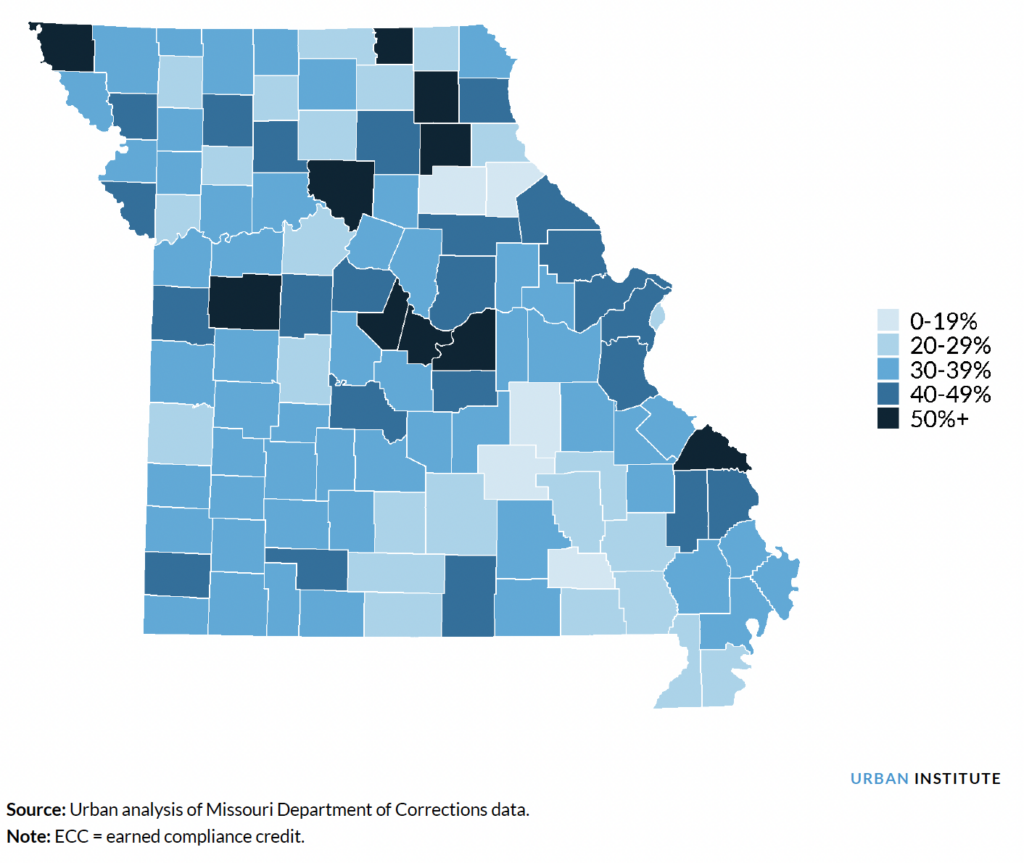

The proportion of the eligible population that has received an ECC discharge has varied across counties (figure 16). This likely owes to the discretion provided to judges in the earned compliance policy enacted in 2012, discretion that was expanded in 2018 by the state legislature. House Bill 1525 (2012) allowed judges to make a motion before the first month in which someone can earn compliance credits finding them ineligible to earn credits because they have a certain offense, because of the nature and circumstances of their offense, or because of their history and character. Such motions are supposed to indicate that a longer term of probation, parole, or conditional release is necessary for the protection of the public or the guidance of the person. House Bill 1355 (2018) gave discretion to the court and the Missouri Board of Probation and Parole to rescind a person’s credits if a hearing is held after a violation report and the person is found by the court to be ineligible because the violation justifies a longer supervision term.

Figure 16: Shares of ECC-Eligible Closures Ending in ECC Discharge by Missouri County in 2018

Supervision Sentence Lengths and Time Spent under Supervision Have Decreased since Earned Compliance Credits Were Implemented

Between 2008 and 2015, the average supervision sentence in Missouri hovered at 55 and 56 months. By 2018, sentences had shortened to an average of 50 months.

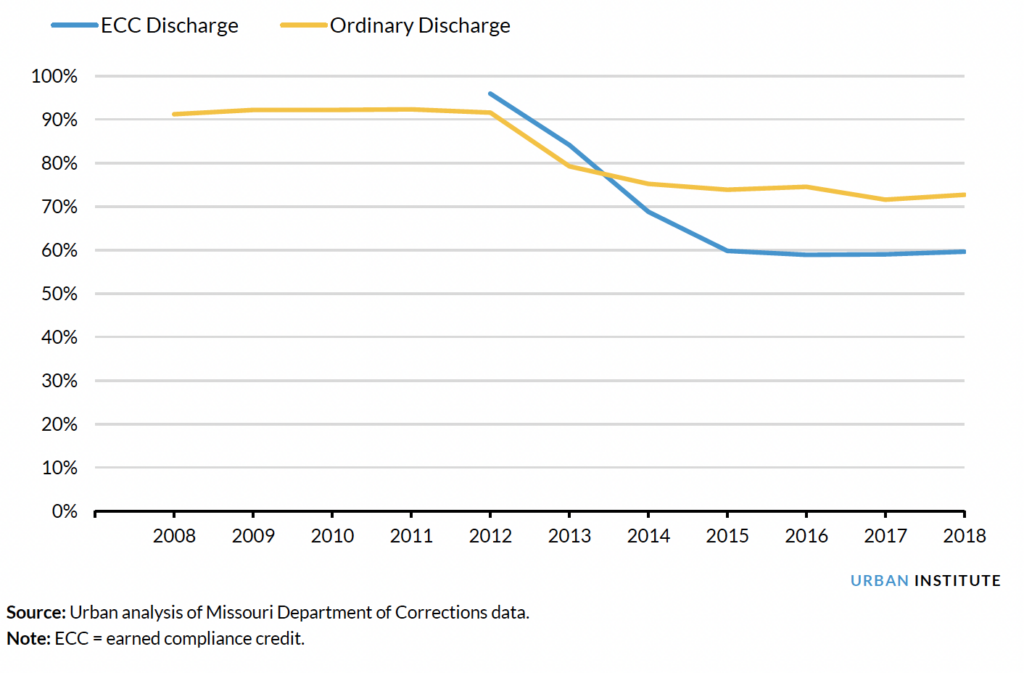

The ECC policy was expected to impact time spent under supervision, and it has. Time spent under supervision among people who are ECC eligible and who successfully complete supervision started to shorten immediately after ECCs were implemented, from 47 months in 2012 to 33 months in 2015 (where the average has remained). In 2018, people who discharged through ECCs served 32 months under supervision on average. During that period, people who were ECC eligible but who discharged through ordinary means served 36 months on average in 2018. Further, people who received ECC discharge served less of their total sentence (60 percent on average) than ECC-eligible people who received ordinary discharge (73 percent on average; figure 17).

Figure 17: Percentage of Full Sentence Served among All ECC-Eligible Closures by Discharge Type in Missouri, 2008 to 2018

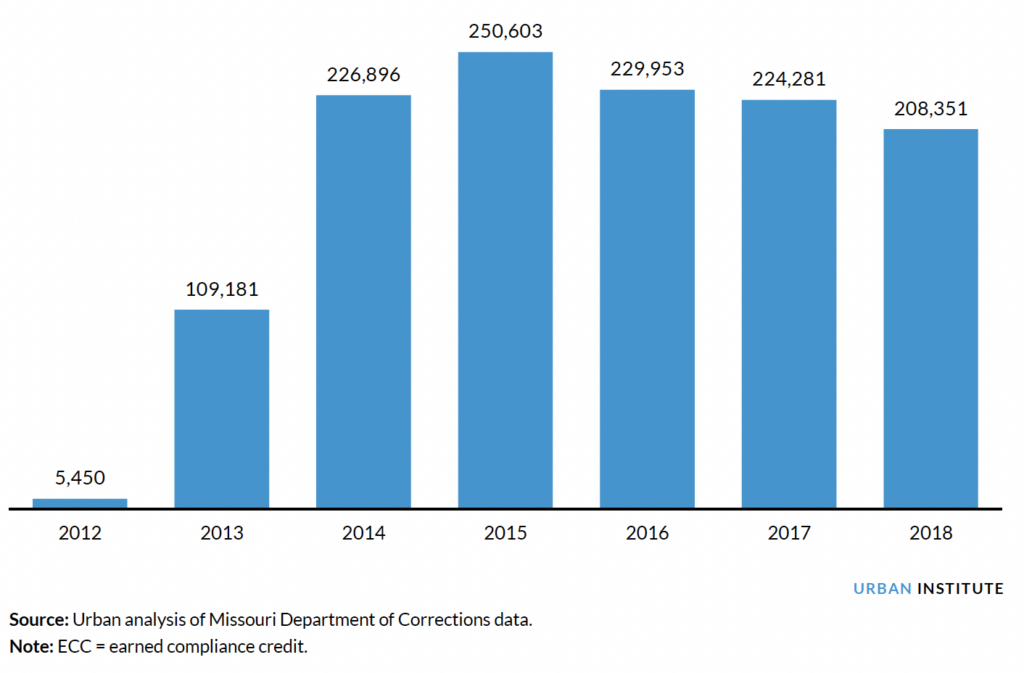

From 2012 to 2018, people who received ECC discharge reduced their sentences by approximately two years on average. In 2018, this aggregated to 208,351 total months “saved” from supervision terms owing to the ECC policy (figure 18), and from 2012 through 2018, this totaled approximately 1,255,000 months of supervision time.

Figure 18: Total Months Saved for ECC Discharges by Supervision End Year in Missouri

ECC-Eligible People Who Successfully Complete Supervision Have Fewer Violations Than ECC-eligible People Who Do Not Complete Successfully

Unsurprisingly, people who were ECC eligible and successfully completed supervision between 2012 and 2018 had fewer violations on average than those who did not complete successfully. In 2018, people who ended supervision with incarceration averaged 3.9 violation months (i.e., months in which they did not earn credits), whereas people who received ordinary discharge averaged 2.7 violation months and people who received ECC discharge averaged 2.1 violation months.

Recidivism Rates Are Low among People Completing Supervision via ECC Discharge and Ordinary Discharge

Missouri’s recidivism rates for people successfully discharging from supervision are low.14 Among people who are eligible for ECC discharge and complete supervision via ECC or ordinary discharge, new felony sentence rates within three years of ending supervision are below 10 percent, and rates of new prison admissions are below 5 percent. Comparing people who closed via ECC discharge and people who closed via ordinary discharge, there is little difference in the one-, two-, and three-year rates of new felony sentences and new prison admissions. Further, people receiving ECC discharge have similar three-year felony reconviction rates regardless of how early they terminate their supervision.

We conducted an analysis of the effect of ECCs to examine whether the recidivism rate for people under supervision after ECCs were implemented was similar to the rate before they were implemented (see the technical appendix for more information). Comparing two similar groups of people—one group that would have been eligible for ECCs before the reform but did not receive it and one group that was eligible and received the ECCs after the reform—we found that the three-year felony reconviction rate remained very low: this rate was 7 percent for the postimplementation group and 6 percent for the preimplementation group. Although this difference was statistically significant, the rates were not substantially different. Reincarceration rates did not differ.

Implementing Earned Compliance Credits Has Been Challenging

Missouri Department of Corrections (MDOC) staff we interviewed consider ECCs an effective incentive. Implementing the policy, however, has been difficult for them. Staff consider the criteria for eligibility and exclusions confusing and difficult to track. Moreover, these criteria have changed, exacerbating the confusion. In addition, the MDOC does not have a quality assurance system in place to ensure accuracy of ECC entries in its data management system. Incorrectly entered data can result in inaccurate supervision time calculations. In addition, MDOC staff expressed frustration that judges—who have discretion to disallow ECC discharges—apply the policy inconsistently.

Further, effects of the policy have differed across counties, leading to varying views among supervision officers across the state as to whether ECC discharges have made caseloads more manageable. As caseloads decrease in one supervision district, probation officers are sometimes transferred to a different office where additional coverage is needed. This can cause caseloads to return to their previous level in offices from which probation officers are transferred.

To support implementation and respond to questions from MDOC staff about ECCs, the MDOC created a SMART team that consists of community supervision staff who are subject matter experts from different regions of the state. This team can, for example, interpret policy, help staff understand ECC reports, and help community supervision staff understand ECC calculations in the MDOC computer system. The SMART team has been essential in helping practitioners across the state understand the implications of court decisions and eligibility criteria adjustments during the implementation period.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although Oregon and Missouri have taken different approaches to earned discharge, they share some commonalities, including the following:

- In both states, people who receive earned discharge serve less of their supervision sentence than people who receive most other successful completion types.

- Earned discharge “saved” more than 61,000 months of supervision time in Oregon from 2014 to 2019 and approximately 1,255,000 months of supervision time in Missouri from 2012 to 2018. In Oregon, this means that a person’s supervision term closing to earned discharge is shorter, on average, by 13 months than the supervision sentence length. In Missouri, this means that a person finishing supervision through an ECC discharge has a shorter supervision term by about two years than their supervision sentence length.

- People closing their supervision terms through earned discharge or ECCs have similar recidivism rates as people who were otherwise eligible for earned discharge but closed to other successful completion types. Moreover, in Missouri, similar groups of people had similar rates of new felony incarceration before and after ECCs were implemented, and in Oregon, a group of people who completed to earned discharge had lower overall reconviction rates, but slightly higher felony reconviction rates, than a similar group of people who did not close to earned discharge.

- Supervision officers generally see earned discharge as a beneficial incentive for people on supervision.

- Implementation of earned discharge has been met with resistance from the courts and has proved challenging for supervision officers to implement.

- Rates of use of earned discharge vary within each state when county-level discretion or discretion of certain parties is a large component of the policy design.

Based on these findings, we recommend that states considering adopting earned discharge policies or programs do the following:

- When politically feasible, reduce the discretion of judges and supervision staff to make determinations about people’s eligibility for earned discharge. This will help make the application of earned discharge across different areas more consistent and equitable.

- Ensure definitions associated with eligibility are clear, as simple as possible, and not open to interpretation. This will make office-level decisionmaking easier and will make application of earned discharge more consistent and equitable across a state.

- To gain buy-in from supervision staff and to ensure they do not see earned discharge policies as “extra work,” it is important that information systems can automate the tracking of key dates requiring staff action, and that procedures are in place to ensure the policies are used and applied consistently.

- Evaluate earned discharge policies periodically to determine their impact and share results with all system stakeholders. Examples of what to measure include the number of cases eligible by year and county or region, the number and percentage of cases ineligible because of violations or noncompliance with conditions, the number and percentage of cases receiving earned discharge, and the supervision time saved by cases approved for earned discharge. Knowing whether a policy is having its intended effect can motivate people to use it if it is working and can help stakeholders modify the policy or parts of it that are not working optimally.

- Continue seeking ways to support and encourage people on supervision to comply with their conditions so more people can earn credits toward discharge, and build in multiple opportunities for people to be reconsidered for earned discharge if they are initially denied.

- Determine the extent to which financial obligations alone are a barrier to earned discharge and seek ways to reduce this barrier. This can increase the incentive for people to do well on supervision and increase fairness in the application of the policy.

Notes

- Jake Horowitz, “1 in 55 U.S. Adults Is on Probation or Parole,” Pew Charitable Trusts, October 31, 2018, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2018/10/31/1-in-55-us-adults-is-on-probation-or-parole.

- See, for example, Wodahl, Garland, and Mowen (2017), Wodahl and coauthors (2011), and Gendreau (1996).

- Eligible cases for earned discharge are people on probation and local control postprison supervision for a felony or designated drug-related misdemeanor. In addition, to actually be discharged through earned discharge, people must have fully paid restitution and compensatory fines, have not been administratively sanctioned (not including interventions) or found in violation by the court in the six months prior to earned discharge review for the eligible case, and should be actively participating in the supervision case plan.

- Early termination is a successful closure of a supervision case. To be considered for early termination, a person must have completed at least one year of supervision; must not have been convicted of a violent crime, a sex offense, or terrorism; and must not have committed repeated drug offenses. Compliance with the conditions of supervision, progress toward one’s reentry goals, and other factors are also considered. Early termination is granted by the courts after a petition by a supervision agency.

- In 2021, House Bill 2172 included several changes to the earned discharge policy effective January 1, 2022 (these changes are not retroactive) including expansion of eligibility to certain post-prison and parole sentences, requirement that individuals have a payment plan in place and a willingness to pay rather than a requirement that restitution be paid in full, and a requirement (through administrative rule changes) that compliance standards for determining eligibility are more detailed and consistent across all counties.

- Oregon Administrative Rule 291-209-0020: https://oregon.public.law/rules/oar_291-209-0020.

- Oregon Administrative Rule 291-209-0040: https://oregon.public.law/rules/oar_291-209-0040.

- To allow for sufficient follow-up time, we analyzed people eligible to be considered for earned discharge who were part of the total population admitted to community supervision between 2008 and 2017.

- Please see this report’s technical appendix for more details about the results of this analysis.

- In this report regarding Missouri, references to parole include both parole and conditional release.

- In 2017, Missouri passed legislation restructuring the felony classes in its criminal code. Formerly Class C felonies became Class D felonies, and formerly Class D felonies became Class E felonies.

- Per Section 559.115 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri, at the recommendation of the court, the MDOC may place someone on supervision in a 120-day shock incarceration program or an institutional treatment program.

- Quantitative findings in this section are based on administrative data provided by the MDOC to the Urban research team. This report’s technical appendix provides more information on these data.

- Of note, Missouri does not report recidivism for people who exit supervision unsuccessfully, for instance, through revocation.