Technical Appendix

Table of Contents

This appendix documents the data sources and methodology that supported the analysis in this report. For this report, we used individual-level data of people on community supervision from state criminal justice agencies, and we reviewed policy documents and interviewed stakeholders.

Data Collection

This policy assessment relied on public documents, interviews with stakeholders, and administrative data. Documents, policies, and reports about the earned discharge policies were collected. Stakeholders in Oregon and Missouri participated in interviews with project staff. The administrative data used in our analysis come from two sources—the Oregon Department of Corrections and the Missouri Department of Corrections. Both states provided data on people on community supervision before and after the implementation of their respective earned discharge policies.

Oregon

Policy documents. The authors reviewed relevant Oregon statutes and administrative rule to understand the full details of the earned discharge policy. We also reviewed publicly available reports from the ODOC and met with department leadership to understand the context of state and local control and the policy rollout process.

Interview data. With information gleaned from the policy documents, we developed guides for holding focus groups with and interviewing county-level stakeholders to better understand how the policy was applied, the implementation process, and stakeholder perspectives on earned discharge. Through input and assistance from the ODOC, the authors scheduled and conducted site visits in two counties to interview community supervision administrators and their staff. In addition, the Urban and Crime and Justice Institute team held virtual focus groups with four other counties that were selected based on size, location, and how local supervision is overseen (i.e., whether community supervision is run by the state and county or by a sheriff and local community corrections director). At the beginning of each interview, we explained to the participant the purpose of the study and the funder, made clear that participation was voluntary, and received verbal consent for participation. Virtual interviews were recorded for accuracy in note-taking. A total of 29 people were interviewed to contextualize the findings of the analysis.

Administrative data. Urban received individual-level administrative data from the ODOC on all community supervision admissions (probation, post-prison, and parole) served between January 2009 and December 2019. The data included information regarding demographic characteristics, supervision sentence and terms, risk level, sanctions, and interventions. In addition, we received recidivism data from Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission which included three-year rates of reconviction from time of admission to supervision. Urban worked closely with the ODOC data and research team to select variables for inclusion in the analysis, ensure understanding of the data structure and variable meanings, and check for accuracy and quality.

Missouri

Policy documents. The authors reviewed Missouri state statutes to ensure we understood the details of the policy as written. We also reviewed MDOC policies and documents related to ECCs. Moreover, we reviewed publicly available data and reports from the MDOC on reform efforts in the state.

Interview data. Informed by the review of statutes and policies, the authors developed interview guides for use with focus groups with various stakeholder groups throughout the state. Interview guides were tailored for Missouri and for each individual stakeholder group (i.e., probation and parole officers, supervisors, district administrators, leadership of the Division of Probation and Parole, judges, and people directly impacted by the policy) to better understand how the earned discharge policies are applied, what the implementation process consisted of, and stakeholders’ individual perspective on the use of ECCs. Through input and assistance from state administration, the authors scheduled three small focus group meetings with staff, one with probation and parole officers, one with supervisors, and one with district administrators. Each focus group comprised a cross-section of staff from different regions of the state to ensure practices across the state were adequately represented. In addition, the MDOC connected us with prosecutors and judges to help us understand the use of ECCs. The authors also connected with community support resources to interview people directly impacted by the policy. At the beginning of each interview, we explained to the participant the purpose of the study and the funder, made clear that participation was voluntary, and received verbal consent for participation. Interviews were recorded for accuracy in note-taking. A total of 18 people were interviewed in Missouri to contextualize our quantitative findings.

Administrative data. Urban received individual-level administrative data from the MDOC on all community supervision admissions (probation and parole) served between January 2008 and November 2019. The data included information on demographic characteristics, prior justice involvement, the supervision period, violations, ECCs, risk and need levels, and recidivism. Urban met frequently with the MDOC’s director of research and evaluation to discuss the sample and necessary variables, understand how the policy was implemented in the data system, and review analysis findings.

Methodology

In both states, we processed the administrative data into analysis-ready files. This included structuring the data into a single observation for each unique supervision period for each person and creating many variables, including those related to the supervision sentence, eligibility, credits earned, and recidivism. After the data were processed, descriptive analyses were conducted to understand the sample, policy implementation, and trends over time. We then conducted outcome analyses using propensity-score matching to estimate the effect of the earned discharge policies on recidivism in each state. All data processing and descriptive analyses were conducted in Stata 16. The propensity-score matching was conducted in R version 3.6.3.

Outcome Analysis

This section describes the propensity-score matching method used for each state. Because each state had different earned discharge policies, time since implementation, and recidivism definitions, the approach for each state is different.

Oregon

To assess the impact of earned discharge on recidivism, Urban conducted a propensity-score-matching analysis. People who started community supervision between 2014 and 2017 and received earned discharge (n = 4,315) were compared with a similarly situated group of people who were eligible to be considered for earned discharge but successfully completed supervision through a different discharge type during the same time period (n = 26,656). The “treatment” group consisted of people who started on community supervision between January 2014 and December 2017 who had an eligible offense, had a sentence of at least one year, and successfully completed supervision through earned discharge. The comparison group also started supervision between January 2014 and December 2017, had an eligible offense, and a sentence of at least one year, but they ended supervision through other successful discharge types (i.e., ordinary, early termination, or release to bench probation). We focus on people who successfully completed supervision because unsuccessful completion makes someone ineligible to be considered for earned discharge and thus a poor comparison with people successfully receiving earned discharge.

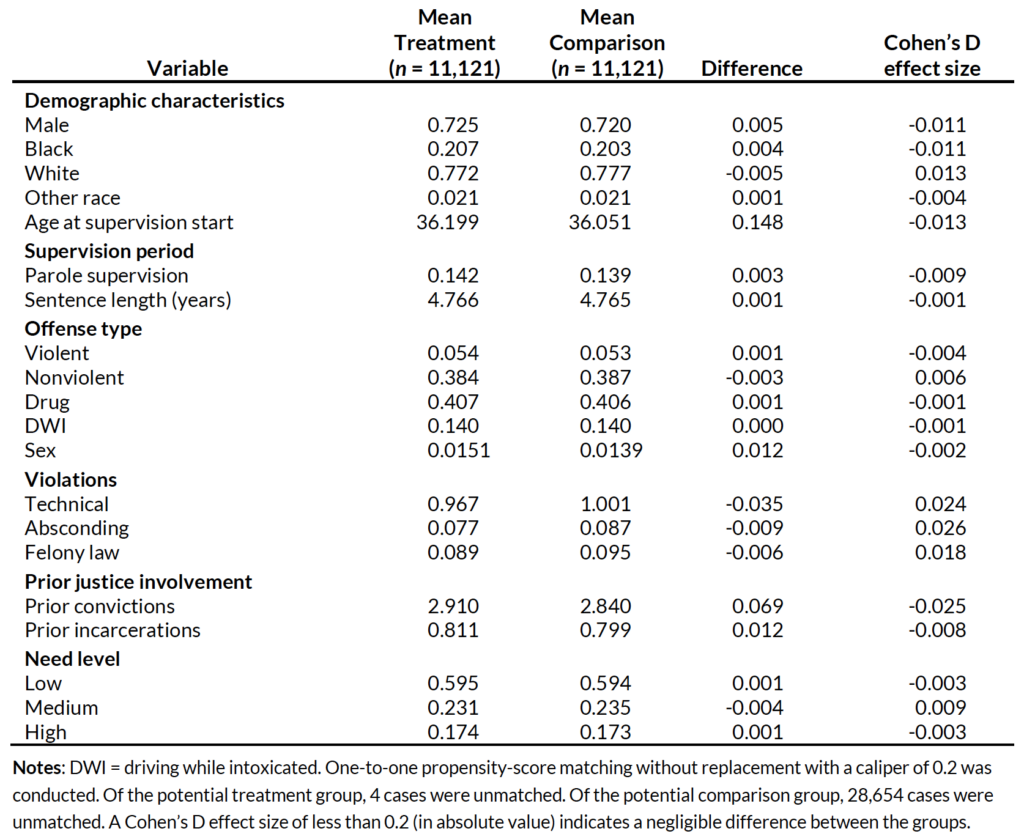

After one-to-one nearest neighbor matching without replacement on demographic characteristics, offense type, supervision sentence length, time spent on supervision, supervision type, number of concurrent sentences, number of sanctions and interventions, county of admission, and risk score, there were no meaningful differences between the treatment group (n = 4,282) and comparison group (n = 4,282), as measured by the Cohen’s D effect size (table A.1).

Table A.1: Oregon Matching Results

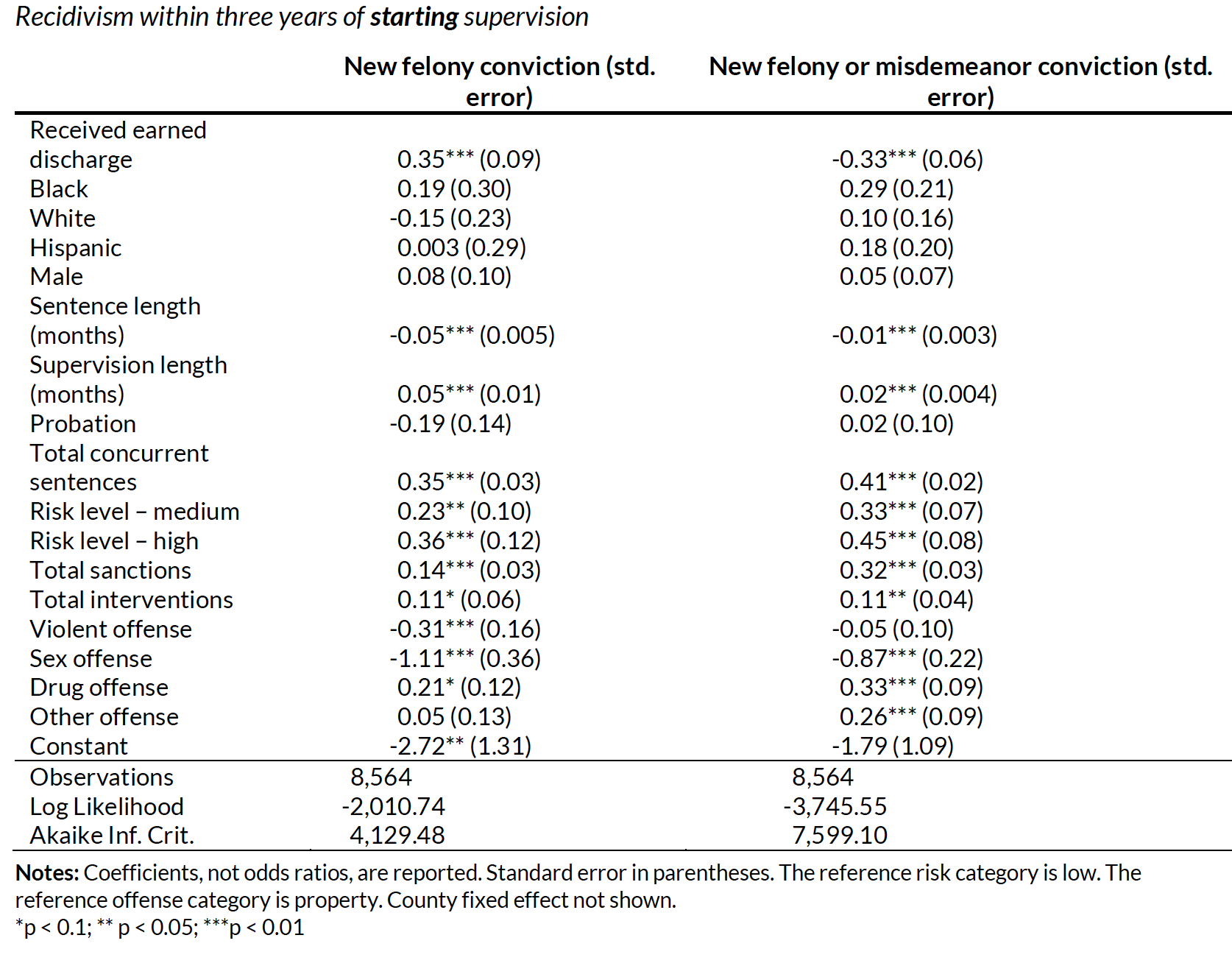

With the matched treatment and comparison groups, logistic regressions were conducted to assess the impact of receiving earned discharge on recidivism as measured by new felony conviction and any new conviction (felony and misdemeanor combined) within three years of starting supervision. The models included the listed matching criteria as control variables. We then estimate the predicted recidivism rate for both the treatment and comparison groups with the models. Note that the average supervision length for the treatment and comparison groups is approximately 20 months, meaning that for the average person in the analysis, 16 months of the three-year recidivism measurement period would occur after ending supervision.

Missouri

To assess the impact of ECCs on recidivism, Urban conducted a propensity-score matching analysis. The “treatment” group consisted of people who started on community supervision after the reform was implemented in September 2012 (and through 2016) who had an ECC-eligible offense, had a sentence of at least two years, and successfully completed supervision through either ordinary or ECC discharge (n = 11,125). We limited the treatment group to those who started through 2016 to allow for at least three years of follow-up time for recidivism. We included all eligible people who ended supervision successfully (i.e., through ordinary or ECC discharge), rather than only people who received ECC discharge so that we could estimate the policy’s broader effect on the eligible supervision population. The comparison group consisted of people who started and ended community supervision before reform (2008 to 2012) who had an offense that would have been eligible, a sentence of at least two years, and successfully completed supervision (n = 39,775). We limit the treatment and comparison groups to only those who ended supervision successfully because those who are revoked are not eligible for ECCs.

We then conducted one-to-one nearest neighbor propensity-score matching without replacement with these two groups. The matching variables included demographic characteristics, offense type, supervision sentence length, supervision type, number of technical and new-crime violations, needs score, prior convictions, and prior incarcerations. There were no meaningful differences, as measured by Cohen’s D effect size, between the treatment group (n = 11,121) and comparison group (n = 11,121) after matching (table A.2).

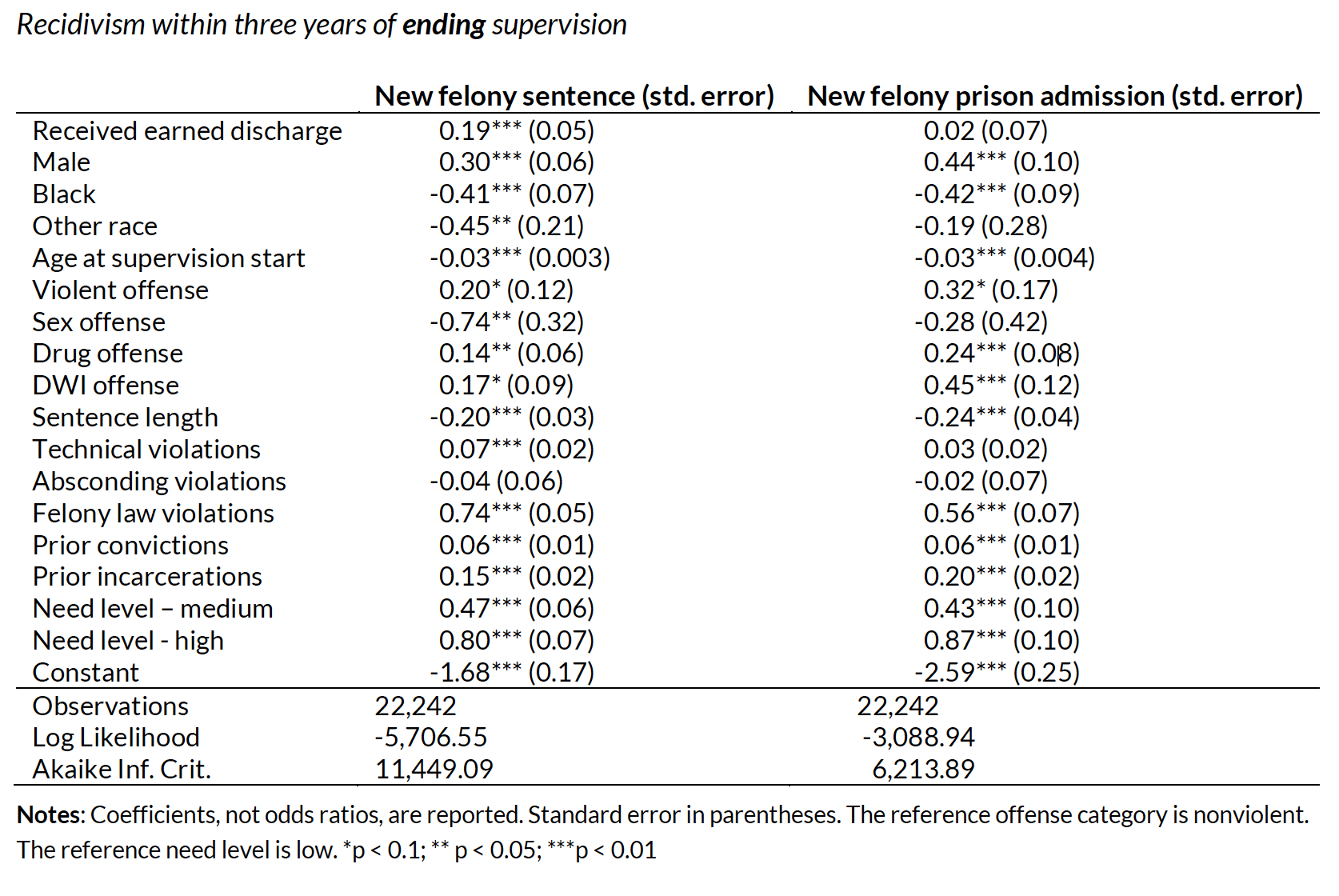

Table A.2: Missouri Matching Results

With the matched treatment and comparison groups, logistic regressions were conducted to assess the impact of the implementation of the ECC policy on recidivism as measured by new felony sentences and new prison admissions within three years of ending supervision. The models included the listed matching criteria as control variables. With the models, we then estimate the predicted recidivism rate for both the treatment and comparison groups.

Results

This section reports the results of the logistic regression analyses conducted after the treatment and comparison groups had been constructed using propensity-score matching. Because the comparison and treatment groups and recidivism definitions are different in each state, the results of each state’s outcome analysis should not be compared directly.

Oregon

After matching and controlling for relevant characteristics, those who received earned discharge had a significantly higher felony reconviction rate within three years of starting supervision, but a significantly lower rate of any (misdemeanor or felony) conviction (table A.3). With each of the models, we then estimate the recidivism rate for both the treatment and comparison groups. Those who received earned discharge only had a slightly higher rate of new felony convictions than the matched comparison group (6.2 percent versus 4.4 percent). However, for rates of any new convictions, the group that received earned discharge had a significantly lower rate (13.4 percent versus 17.6 percent). Receiving earned discharge is associated with slightly higher rates of new felony convictions, but lower rates of any new convictions within three years of starting supervision.

Table A.3: Oregon Logistic Regression Results

Missouri

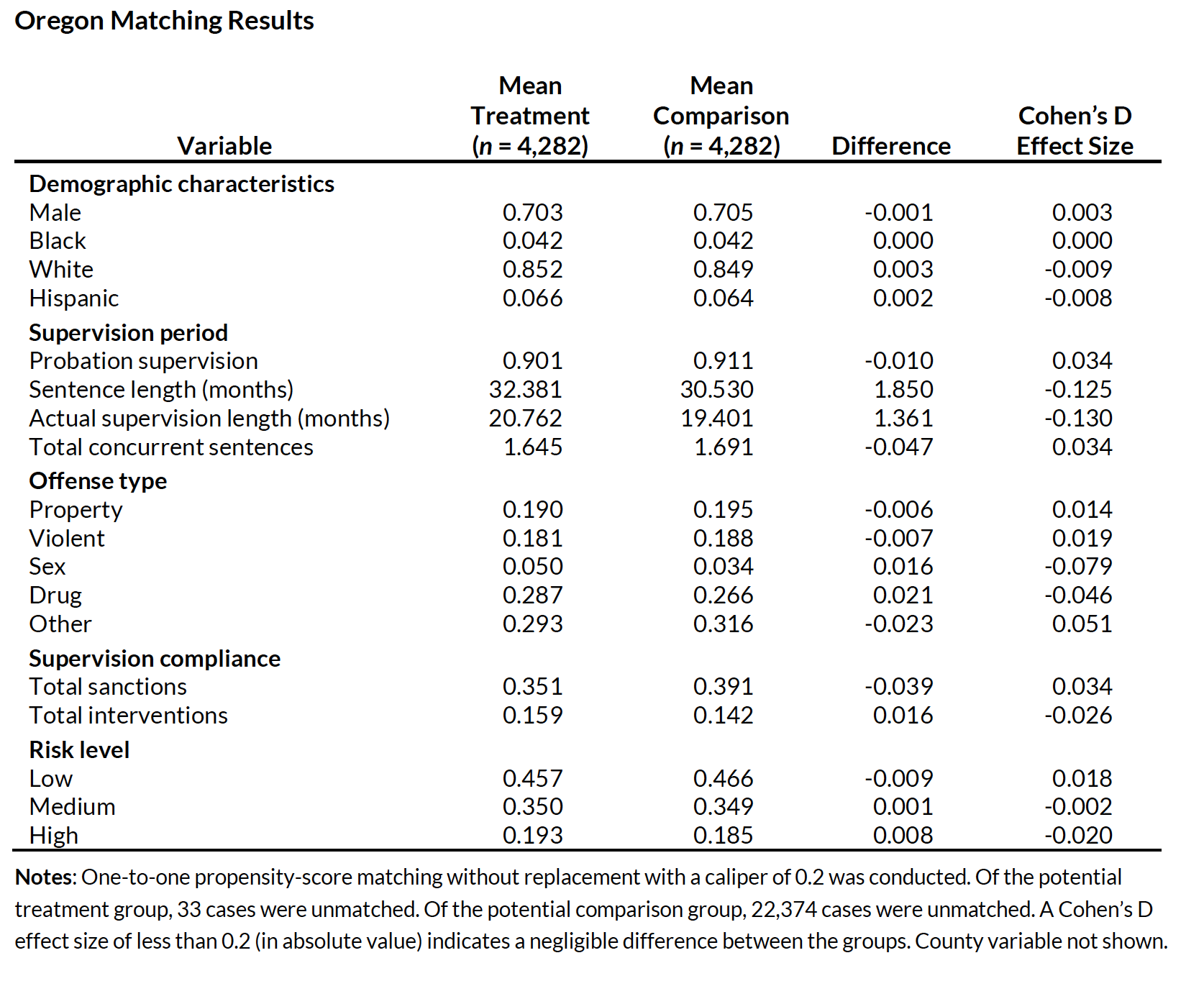

After matching and controlling for relevant factors, people who received earned discharge were significantly more likely to receive a new felony sentence within three years of ending supervision, but had a similar likelihood of having a new felony prison admission (table A.4). We then estimate the recidivism rate for the treatment and comparison groups with each of the models. There was a significant, but not substantial, difference between those who started supervision postreform and were eligible for ECCs and the matched comparison group prereform in rates of new felony sentences (7.1 percent versus 5.9 percent). For rates of a new prison admissions for a felony (2.6 percent versus 2.6 percent), there was no significant difference. When compared with people under supervision prereform who had similar characteristics, exposure to the ECC policy postreform is not associated with any substantial differences in rates of new felony sentences or prison admissions within three years of ending supervision. Both groups have very low recidivism rates.

Table A.4: Missouri Logistic Regression Results